The Background

First, the lay of the landscape: You can see information about the national Maker Faire cycle here, for information about shows and displays. The next big event on the calendar is the National Maker Faire, in DC two weeks from now. You can read here about MakerCon, which I’ve been to and enjoyed, and go here for Make: magazine, to which I subscribe. In two weeks the White House will have events for the National Week of Making, with more information here. Make: had a story on the Maker City Initiative here; Peter Hirschberg has a speech explaining the concept here; and the Institute for the Future had an early report here.

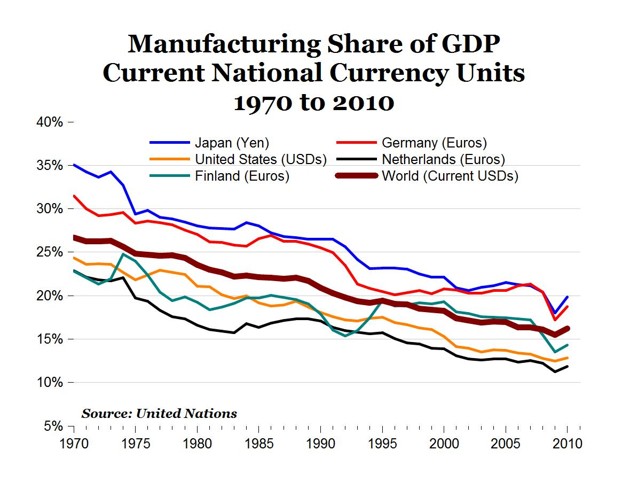

Now, what this movement is and why it matters. Everyone who has heard a recent political speech, listened to a talk show, or looked at the “Made in China” labels in retail stores is familiar with the idea that “America doesn’t make things any more.” There are obvious reasons, and some less obvious ones, why people feel this way. A certain kind of high-volume production certainly has shifted from the rest of the world to China (and elsewhere) in the past generation. As economies get richer, the relative share of manufacturing in their output and their workforce inevitably goes down (as it does for farming—even as absolute output in both categories keeps going up), because service sectors are growing faster. This is true even of economies which much more aggressive pro-manufacturing industrial government policies and corporate practices, like Germany and Japan:

And as manufacturing efficiency grows up, the share of manufacturing jobs goes down even faster than the output share. Everyone’s grandfather worked in a factory; each generation, fewer do.

So there is a real change—fewer Americans have jobs in manufacturing—that seems even larger than it is, because of the kinds of things America still makes. Consumers naturally mainly see consumer goods: TVs, electronics, gadgets, clothes. Those are the fields in which production has disproportionately shifted overseas. Walk into a WalMart or Costco, and just about everything seems to come from China. The higher-end capital goods or scientific equipment from U.S. manufacturers rarely comes before our eyes. (The main exception is Boeing airplanes, with GE or Pratt & Whitney engines.) We see the “assembled in China” labels on Apple computers and phones and over-interpret what that means. The labels conceal the reality that the most valuable parts of a Mac or iPhone come not from China but from richer countries like Japan, Germany, South Korea, and very significantly from the United States.

New Tools, New Firms

Here’s how I finally understood the difference that a new generation of production tools has made: by comparing it to my own business, writing and publishing.

Everyone in journalism knows the line attributed to A.J. Liebling, in The New Yorker: “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Liebling wrote that in 1960. As more-or-less recently as that in historical terms, if you wanted to disseminate your thoughts to people outside your household, you simply could not do it yourself. You had no option but to work through a limited number of powerful, capital-intensive enterprises. You had to convince a newspaper or magazine to publish your writings—because only they controlled the printing presses, delivery networks, and newsstands. (I remember the olden days of wanting to react to something in the news, and then making phone calls or sending letters—!!!, yes, real letters in the mail on paper !!!—to the handful of gatekeepers who ran op-ed pages, hoping you could get their interest.) You had to attract the attention of TV or radio reporters, since only they could get you on the air. If you had a longer story to tell, you had to convince a publishing house to put out your book. Short of going door-to-door with flyers, there was no way to avoid the middleman in this industry. And the people who served as middlemen—the publishers, the broadcasters—were buttressed by the very expensive printing and transmitting equipment they controlled.

Wave after wave of disruption in publishing have been bad for everyone who used to hold that middleman role. (The Atlantic is doing very well right now—so thanks for reading and subscribing!) But the new tools fostered an unprecedented outpouring of expression. Blogs, Tweets, YouTube videos, Instagrammed photos, podcasts, Reddit and Facebook communities, billions upon billions of daily texts messages … One by one many of these might be trivial and some of them destructive. But taken together they produced a totally different form of communication and knowledge, and countless millions of new business operations, all because an advance in production tools.

Tools for Making

Something similar is fostering the maker movement. Since the dawn of the capitalist heavy-industrial era, to succeed in manufacturing you needed capital. You needed money for giant production equipment. Blast furnaces if you were making steel, assembly lines if you were making cars, machine tools if you were making engines, coordinated supply chains if you were assembling complex devices. Then you needed distribution arrangements with stores, and lots of inventory for them to keep in the warehouse, and other impediments that collectively made it hard, expensive, high-stakes, and high-risk for newcomers to enter a business.

This is the equation that the tools revolution of the past few years is also changing for manufacturing. A combination of 3D printing (which allows people to make and revise prototypes onsite, and produce certain high-value, low-volume items themselves, rather than going to a factory); much less expensive laser cutters, milling machines, and other sophisticated machine tools; the evolution of Arduino controls, which allow designers to add sophisticated electronic functions without doing all the coding themselves. You could think of this last function as being similar to simple Embed functions for images or videos online.

In parallel with these technological advances have been organizational changes. For instance, the rise of maker-spaces and shared-work site where people can use advanced machinery for free or at very low cost; and the rise of collaborations among universities, community colleges, established companies, and local financiers in fostering hardware entrepreneurs. One of the most ambitions of those collaborative spaces is “Highway 1” in San Francisco. I wrote about its origins in the magazine back in 2012; you can read a report about its latest “Demo Day,” at which maker groups show off their products, in a TechCrunch story here and see a video here. This video from Highway 1 is obviously promotional, but it demonstrates the changes I am talking about and rings true to what I have seen and heard from entrepreneurs there (I have met and interviewed some of the people you see here).

What It Means in Practice

“This would not have been possible ten years ago,” Venkat Venkatakrishnan, the CEO of a unique and famous maker space called FirstBuild, told me in Louisville earlier this year. FirstBuild is unique because it was created by GE, as a subsidiary of its appliance division and as a deliberate effort to bring the nimble maker spirit to its design process.

“What has changed is that the maker movement has figured out a group of technologies and tools which enable us to manufacture in low volume,” Venkat (as he is known) said. Big manufacturers like GE built their business on high-volume, factory-scale, very high-stakes production, where each new product means a bet of tens of millions of dollars. FirstBuild is mean to explore smaller, faster, more customizable options.

“Now you can get a circuit board mill for $8,000. If you are looking for a circuit board for an appliance, earlier the only chance of getting it was from China. Today I can make boards here and ship them out quickly. Similarly with laser cutters—not big ones but small ones, where I can cut metal right here. It’s a huge advantage, and these things did not exist ten years ago. In those days you couldn’t hack the kind of creative solutions we are seeing now.”

Tomorrow FirstBuild and its parent GE Appliances division are expected to complete a long-announced deal that will transfer ownership to the giant Chinese appliance maker Haier. (GE had previously planned to sell to the Swedish firm Electrolux, which has a much bigger presence in the U.S. market than Haier does, but it called off the deal last year after resistance from U.S. anti-trust regulators.) Both GE and Haier have said that that all factories and facilities will stay where they are (Electrolux had planned a move to its existing sites in North Carolina); that the GE Appliance and FirstBuild management will be unchanged; and that the FirstBuild start-up mission will continue too.

That’s the high-level corporate news. In the next installment, more details on exactly what FirstBuild has underway, how that parallels efforts in other parts of the country, and what this Maker energy might mean for the country’s ability to foster new companies and create better jobs.