People understand the world through stories. People absorb their stories in ever-expanding ways. The purpose of this post is to preview our commitment to a powerful, emerging form of digital story-telling, which we’ll be using frequently in this space.

The human fascination with stories is eternal. The means of conveying those stories continue to change. People now listen to broadcasts, or podcasts – as they listened to storybook tales from their parents when they were children, and as their ancestors listened to poems and legends in village gatherings countless centuries ago. They read stories – on large and small screens, on paper, from graphic novels, in other ways. They watch stories—in movie theaters, on TVs, in live performances on the stage, on small devices in their hands. They hear the music of stories—in country ballads, in hymns and anthems, through opera. They envision the stories that happened leading up to, and starting after, the instant-in-time captured in a photograph or a famous painting, or imagined in a piece of children’s art. They dream in stories and try to apply them to the waking daytime world.

The power of stories, through human history, has grown as new forms of story-telling have continually added to the tools previously devised. People didn’t stop listening to stories, even when movies made it possible to see them acted out. People didn’t stop reading stories, even when a picture became worth a thousand words. Each new means of communication has given more people more options for conveying more of the stories they have to tell. The village story-tellers could reach only the listeners who joined them around a campfire. With radio waves, they could connect with people beyond the range of their own voice. With recordings, they could connect beyond borders of place or time.

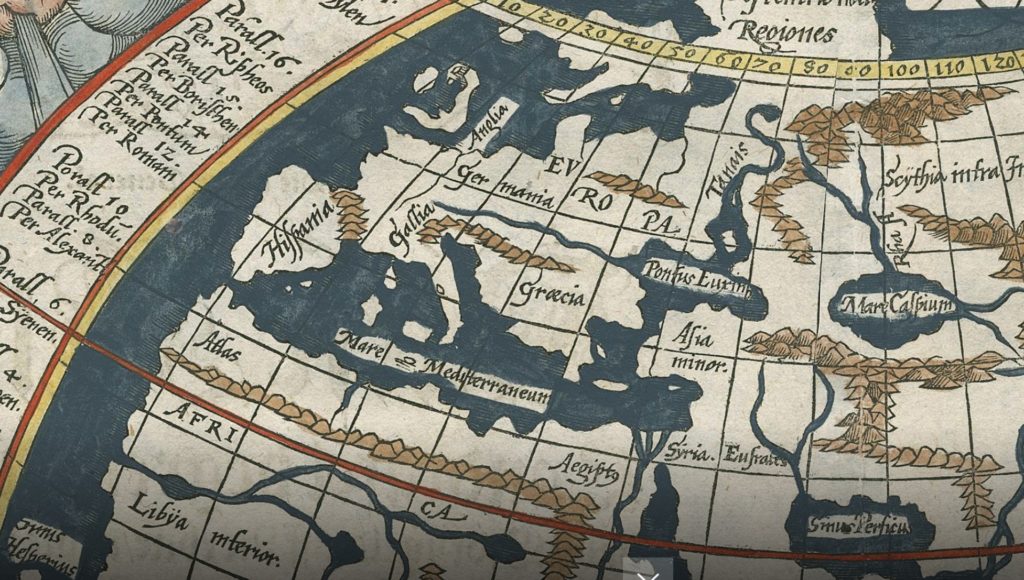

In the array of tools for telling, maps have always played an important role. Children’s maps of buried treasure. Early maps by Ptolemy, with the Earth as the center of the universe and the Mediterranean as the center of the world. (Thus its name.)

The maps that led Columbus to think he had landed in the vicinity of India. (Thus the name “West Indies.”) The maps that track the positions of armies in a war, or infections during a pandemic, or drought and fire patterns as the climate changes, or voting patterns after an election. Where a picture can be worth a thousand words, the right kind of map can be worth even more.

Some of the right kinds of maps, for this era, are the “StoryMaps” developed by our friends at the digital-mapping company Esri. We’ve written about Esri, its technology, and its visions before. Today we offer a very brief introduction to what will be an ongoing exploration of the power of this technology.

In simplest terms, story maps are ways to combine an array of digital presentations–writing, photography, videos, sound recordings, and, of course, related maps–to convey stories and ideas. Allen Carroll, a former Chief Cartographer for the National Geographic, has been a leader of StoryMap (their official name) development for Esri from the start. He and his colleagues offer a primer about the concept here.

The easiest way to suggest the possibilities of these tools is to give a very brief set of illustrations:

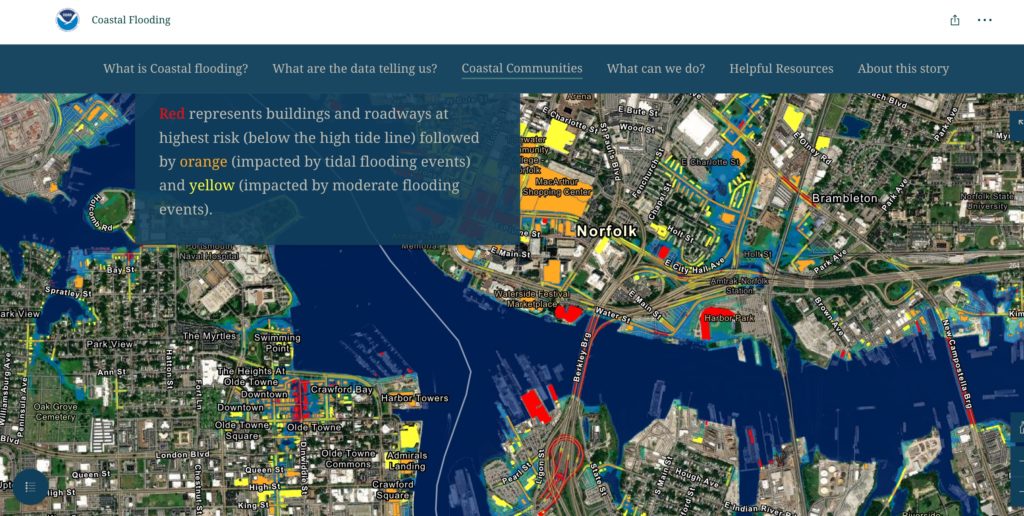

—Here is how a story map can convey a concept—that of the scale of the various uses to which human beings place the Earth’s limited land area. It is the Living Land StoryMap, from a larger collection called Living in the Age of Humans. An important related map, based on similar technology and published in the New York Times, is worth a serious look, here. It helps people visualize what specific portions of the Earth’s surface are most crucial in protecting its biodiversity. A dizzying roller coaster-style survey of the world’s highest and lowest points is here. Another map that helps envision what rising sea levels will mean to coastal communities is here (and below):

—Here is how a story map can take you to a place you will probably never visit yourself. It is Alex Tait’s chronicle of Mapping Mount Everest, which includes one of the most celebrated photos ever taken there.

—Here is how a story map can convey sounds, voices, and atmosphere, with “Voices of the Grand Canyon,” including testimony of many indigenous people there.

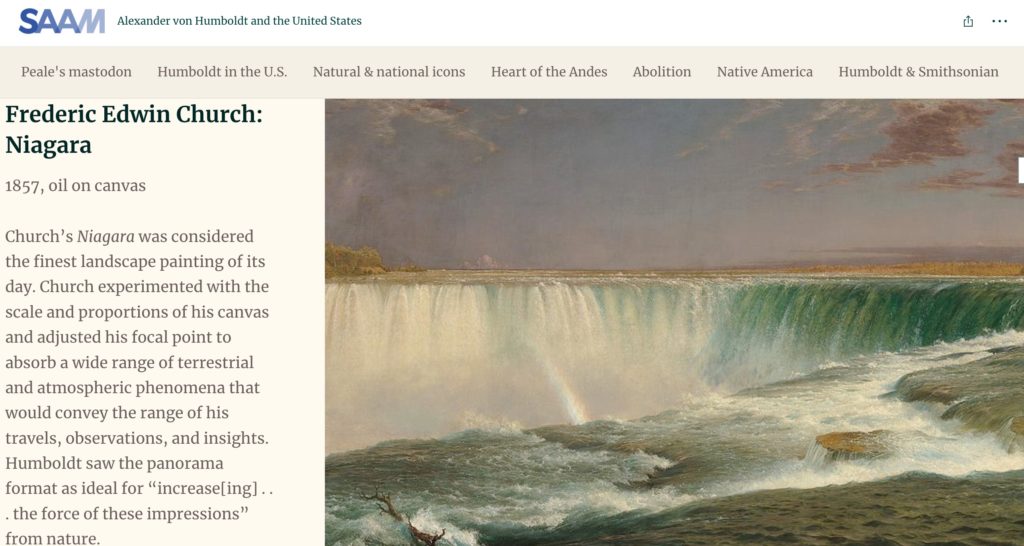

—Here is how a story map can enliven history, with “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States,” a chronicle of an exploration of the continent more than 200 years ago:

—Here is how young students can use story maps to explore issues that will determine their future, through a NOAA project. It’s worth noting that Esri has donated its mapping software for free use by students at most levels of schooling and by most NGOs.

—Here is how some of the most accomplished map-makers and explainers have used this tool.

—And here are Allen Carroll’s insights about how maps, stories, and imagination interact, and also on the “9 Steps to Great Storytelling” that he has distilled.

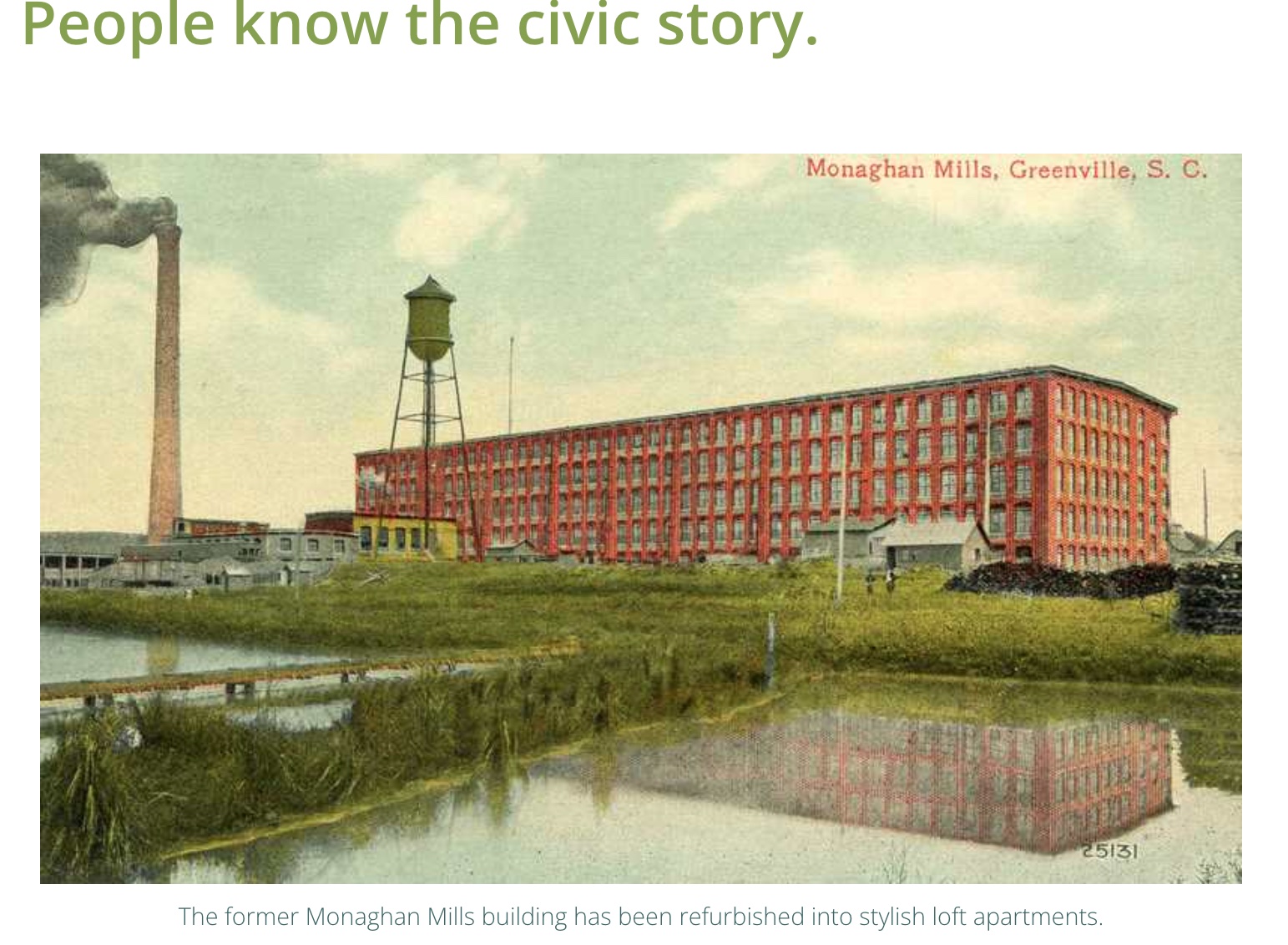

What does this have to do with locally driven American renewal? Progress in any community depends on knowing the civic story, and these newly accessible map-making tools are one more way for people to understand where they have been, and where they might go.

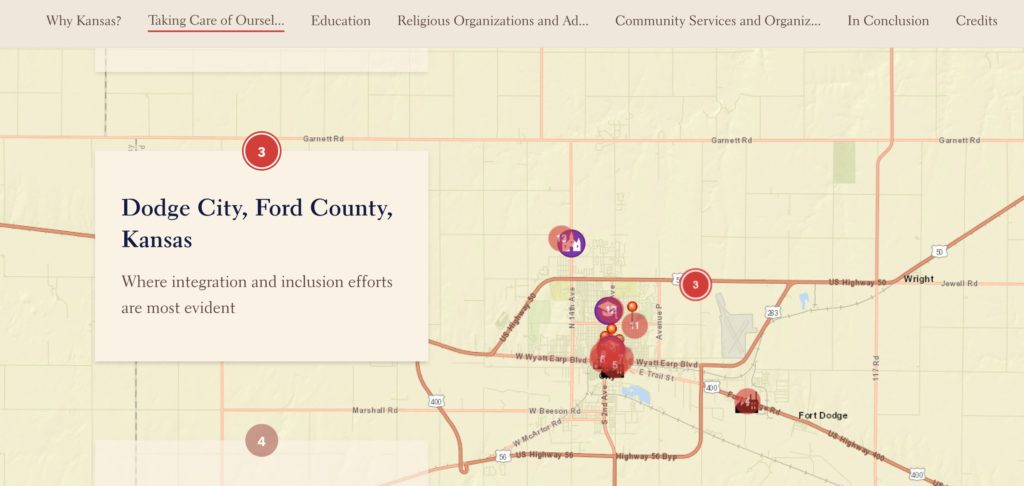

One illustration is from the town of Kent, Ohio, where the Main Street Kent organization and the Kent Historical Society have produced a story map of the town’s industrial heritage. Another is from Dodge City, Kansas, for which Aerin O’Malley, Guadalupe Guerrero, Camila Avila-Martinez produced a map of the city’s response to its changing demographic mix:

These are both story map presentations of themes that we have examined in our book and movie, and in many posts on this site. Other examples of telling civic stories through story maps are here.

Our ambition now will be to feature and create more of these, to share tips about their most effective use, and to offer one more way to today’s citizens to understand their communities, their realities, and their most promising paths forward. We think the history of journalism, story-telling, and civic engagement in our times will include one of this era’s new tools, the story map. We do our best to illustrate its potential.