I mentioned yesterday that several local initiatives could mean as much to their communities or states as the outcome of most national races. The two historical examples I naturally think of are from California, Propositions 13 and 187. Prop 13, which was passed nearly 40 years ago, strictly capped property taxes—and in so doing helped shift California’s public schools from among the best-funded in the country, as they were in my school days, to among the worst.

Proposition 187, which was passed in 1994, limited public services for illegal/undocumented immigrants. It was a Republican-backed measure, championed by then-governor Pete Wilson, and was very unpopular with Latinos. You can’t prove exact cause and effect, but there’s no denying this change: In the decades leading up to Prop 187, the California of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan was a reliably Republican state in presidential elections. Since then, coincident with its growing Latino population, California has been the Democrats’ most important bulwark. (In the 11 presidential elections from 1948 to 1992, Harry Truman through Bill Clinton, California went Democratic only twice. In every election since then the Democrat has won, with margins that keep going up.)

Two of the measures I mentioned yesterday were city-wide. One is San Bernardino’s long-overdue reform of its dysfunctional city charter, via Measure L on today’s ballot. The other is Stockton’s attempt, through its Measure M, to approve a very small (quarter-cent) sales tax increase to fund libraries and recreation centers for young people and families who now badly lack them.

Stockton, once a site of commercial and industrial wealth, has become one of California’s poorer cities. Many of its people are immigrants; the population mix is roughly “40/30/20/10,” or roughly 40% Latino, 30% white, 20% Asian, and 10% black. “We’re the most diverse medium-sized city in America,” Mas’ood Cajee, a Stockton dentist who is one of the leaders of the Yes on M movement, told me yesterday.

Many of these children start out with varied disadvantages: of family income, language, unsafe neighborhoods, underfunded schools. Through the past decade, as Stockton was hit like other inland-California cities by the sub-prime real-estate crisis and then by its municipal bankruptcy, funding for almost everything has been cut. That’s why I find it impressive that the city council voted unanimously to fund libraries and rec centers again, and that most local civic groups have supported it. I hope the voters agree today.

Why do I care about this? Partly because civic governance is at the moment more encouraging than national politics. And partly because Deb and I have seen other cities go through a similar process, with positive results.

Consider the example of Dodge City, Kansas. Dodge City and its environs in western Kansas are politically and culturally much more conservative than even inland parts of California. But their ethnic situation is similar—as we’ve discussed before, the meatpacking centers of Dodge City, Garden City, and Liberal have become majority-Latino—and they also have faced civic challenges.

Dodge City’s answer, nearly twenty years ago, was something called the “Why Not Dodge” initiative. In 1997 the city’s voters approved a permanent sales-tax increase totaling one percent, with the proceeds to be used for long-term civic improvements. Now nearly everywhere you look in town, there’s another project funded by the ongoing flow of Why Not Dodge revenues. They include: a large public soccer complex; the Cavalier and Legends Park baseball and softball fields; an auto raceway; a new civic center; a large expo site; a brand new aquatics park, the Long Branch Lagoon, which was in very heavy use during our visits last summer; repairs on a historic railroad depot; and more.

In effect, a very conservative community voted itself an open-ended tax to pay for long-term infrastructure improvement. Why was this possible there, when its counterparts at the national level are gridlocked out of consideration?

“We may be ‘conservative.’ but we’re progressive,” Melissa McCoy, who grew up not far from Dodge City and is now the city’s Project Development Coordinator, told me. “There was a time when we had a really negative self-image as a town. But people thought, If we won’t invest in ourselves, how can we expect anybody else to? It was a matter of getting the community behind it and realizing that we needed to back ourselves up to get outside investment and support. Now we’re starting to see it pay off.”

I asked Joyce Warshaw, an elementary school principal who is Dodge City’s mayor, whether there was any mystery or contradiction in a politically conservative community enacting a permanent infrastructure-improvement tax. Warshaw is herself a Republican, who ran (but lost) in the GOP primary for the Kansas state senate this year.

“Not at all,” she said. “It’s been so beneficial for the city. This community is incredible in embracing things that need to happen for the city. I think many people saw how important it was to raise taxes just a minute little bit to raise our quality of life here in Dodge.” And to anticipate a question from those who haven’t been there: cities in this part of Kansas cannot define themselves in narrow ethnic-enclave terms. The railroad and cattle businesses have historically brought a range of people to western Kansas, and Dodge City is now majority Latino. (As Deb and I have discussed here, here, and here.)

We’re nearing poll-closing time here on the East Coast, and I won’t pause now to untangle the ways in which local-area communitarian impulses do and do not convey to the national level. That’s for later, at greater length.

The point for now, on election day, is to note that the work of investment and civic improvement still happens in the country; it just doesn’t seem that way, since national politics have been so discouraging. In this spirit, I hope that San Bernardino’s voters approve Measure L, to put their city on a better course; that the necessary super-majority of two-thirds of Stockton’s voters approve Measure M; that statewide voters defeat Proposition 53, which would hamstring big statewide investments; and that Dodge City’s investments continue to pay off.

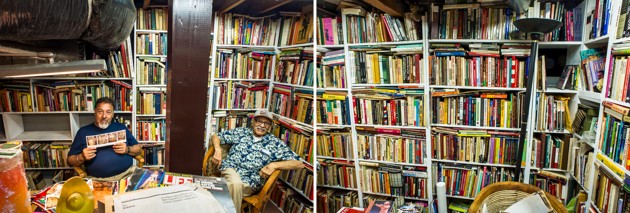

As I head back to vote-watching, here is one more photo from Robert Dawson’s extraordinary series “Raising Literacy: A Photographic Survey of Libraries and Literacy in Stockton and San Joaquin County.” Dawson and Ellen Manchester have documented the role of libraries around the country and the world, including in his book The Public Library: An American Commons.