I love maps. And I think their biggest days, and also their biggest challenges, are still ahead. That will be the theme of several upcoming posts, briefly introduced with this Proust-spirited and deliberately teaser-style one today.

As a kid, I had maps of all sorts on my bedroom walls. Maps of how and when peoples from other continents had arrived in the Americas. Maps of the Roman Empire at its peak–and Alexander’s, and Genghis Khan’s, and the British and French and Portuguese and Ottoman. Maps of rivers and their watersheds across North America–and of rainfall levels, and soil types. Maps of tectonic faults, starting with the famed San Andreas that ran right through our little Southern California community. (And because of which my elementary school building had to be razed, as an earthquake risk.) Maps of how borders changed in Europe, and Africa, and Asia, after revolutions and wars. Maps of the language families of the world, and of expeditions to the North and South Poles.

A globe on the desk. A planetary map on the ceiling. Topography and elevation maps for Boy Scout hikes.

You get the idea.

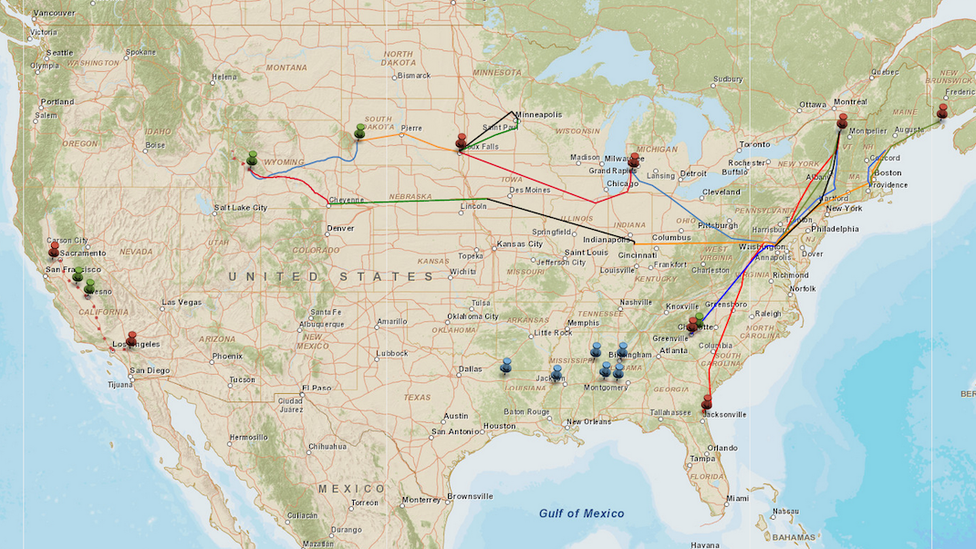

And I love mapping to this day. For instance, through our journeys around the country originally for the Atlantic’s “American Futures” series, we frequently offered maps — for instance, the one below, showing the initial rounds of our interviews and travel, or the ones linked here, about race-and-economics in the deep South, or this one, by our colleague John Tierney, about the streetscape scene in Allentown, Pa.

This is what I see over a desk in my office, a present from one of our sons.

And this is my favorite among our household trays — made of laminated wood, and received as a gift on a reporting trip to northern Michigan.

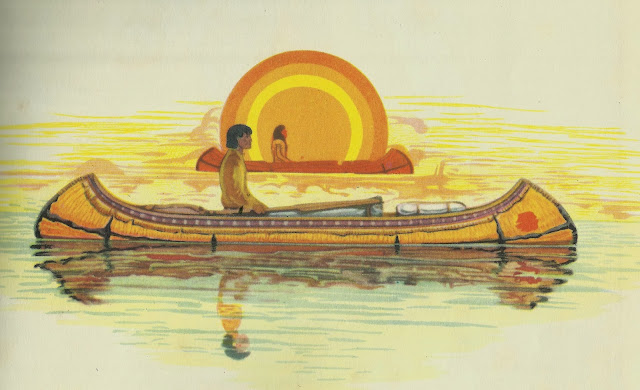

But as I’ve been thinking about the explanatory and imaginative power of mapping, I’ve returned to a book I remember poring through time and again in childhood years. This was a work of “geo-historical-fiction” called Paddle-to-the-Sea. (For “Proust-spirited” purposes, the role of the madeleine is played by the canoe and paddler in this book.)

The book’s author was a then-renowned artist-turned-writer named Holling Clancy Holling. It was published just before the U.S. entered World War II, and it won countless children’s-literature recognitions in the following years. A brief film inspired by the book came out in the 1960s and had a wide following for a while. You can see it at the Canadian National Film Board’s site here. I got the book as a birthday present when I was seven years old, and read it more frequently than I can count through my grade-school years.

The Paddle saga, and Holling himself, appear barely to be remembered now. When I checked today, the book was #433,830 in Amazon’s popularity ranking. And for the record, Holling, who was born in 1900 and had a fascinating career that included living among and writing extensively about Native Americans (plus being an Art Institute of Chicago graduate, and a taxidermist), sometimes wrote in ways that reflected the language and attitudes of white Americans of his era. For more, see this and this — yet also these admiring contemporary comments about the work he and his wife, Lucille, published in the 1930s: The Book of Indians.

Still, the imaginative power of Paddle and other H.C. Holling books still reaches some of today’s young readers and their families, as you can see an example of here. And I have been thinking about it, Proust-madeleine style, as an introduction to a modern advanced-technology question I am thinking about, more than 60 years after my first encounter.

The story in Paddle-to-the-Sea is of a small carved, wooden figure of a canoe with a paddler inside. On the bottom of the canoe are inscribed these words: “I am Paddle to the Sea. Please put me back in the water.” An indigenous boy in northern Ontario carves the little canoe-and-paddler and adds the inscription, and then places them on a frozen stream. He knows that when the spring thaw comes, the snowmelt will carry them to Lake Nipigon and then to Lake Superior, and through all the Great Lakes and beyond.

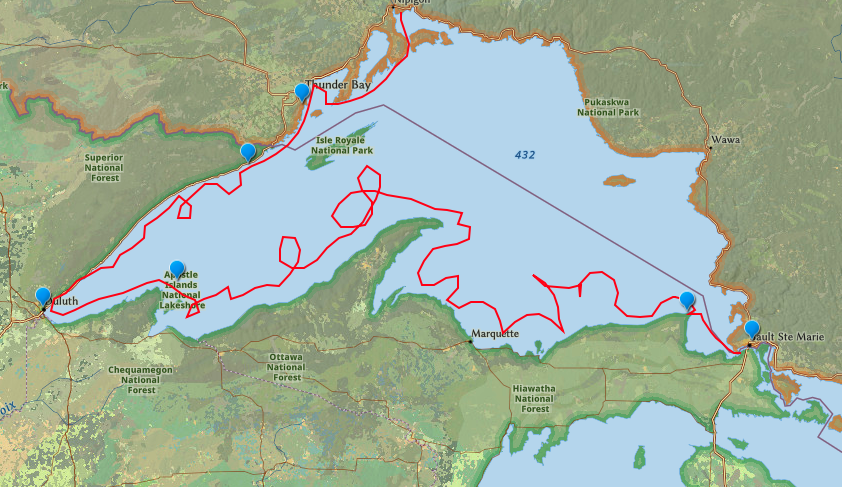

The wooden craft and its occupant endure many adventures and hardships on their subsequent long journey. I won’t ruin the suspense by revealing where they end up–actually, it is more suspenseful than you’d guess. As a small sample, here is an idea of how the winds, current, shipping traffic, and other forces buffet them around Lake Erie–from their entrance through Lake St. Clair near Detroit, to their exit over Niagara Falls. And this is far from the most perilous part of their trip.

It’s a story of nature, and of circumstance, and of human intervention. But I remember it most powerfully as a story about geography. As a boy in inland California, I’d barely had any idea of which Great Lake was which, or even how many of them there were. (Six? Three?) But following each part of Paddle’s journey gave me a mental picture of how one lake connects to the next, how they were part of one big water system “set like bowls in a hillside” as the book puts it, why they flowed in the direction they did.

Holling Clancy Holling was very conscious of his role as a “geo-narrator,” and some of his other books were even more explicit in using map-stories as a way of conveying information about history, topography, wildlife, and culture. Indeed, one of the (few) criticisms of his later book Minn of the Mississippi is that it is too obviously didactic. Minn follows the journey of a snapping turtle, from the headwater-rivulets of the Mississippi River, in Minnesota, to its broad, brownish mouth, in the Gulf of Mexico, as a vehicle to explain the geography and history of the central part of the country. This book came out ten years after Paddle, and won the Newberry Award and other acclaim.

The point about both books is the way they used maps and geographical narratives to shape young people’s awareness of what was around them. Given their popularity and prominence in mid-century America, I can’t be the only Boomer-era person whose mental images of the world were influenced by books like these. And I raise the books’ geographic emphasis now, many decades later, as a prelude to an upcoming report on what I learned at a (virtual) gathering this month of many thousands of the leading cartographers, geographers, and map-makers around the world:

— Based on what I saw and heard, I am more than ever aware of how technology is about to add dramatic new power to maps’ ability to shape our consciousness of the world. People have always understood reality through stories: this is the thread that connects Plato and Homer, to Walter Lippmann, to the most popular podcaster or TikTok influencer now. But for technological reasons maps and geographical imagination may be about to take a big step in story-telling power — as I will plan to lay out. Holling Clancy Holling set out to write “geo-historical” fiction. I have been thinking about the rapidly expanding, digitally enhanced potential for “geo-journalism.”

— Based on what I saw and heard, there is still enough time, but barely enough time, to increase the chances that this new view on the world is a reality-based one–informative rather than distorted, another step toward knowledge and connection rather than another step into the tech-based misinformation abyss.

Sixty years ago this spring, the boy-wonder FCC commissioner Newton Minow gave his prescient warning about the use and misuse of the communicative power of TV. Minow was 35 years old when he gave that “Vast Wasteland” speech, he is 95 years old now; and he is still very much active and engaged on questions of public information and media responsibility. Part of the fate he warned about still occurred–but he set out a model of what the best of TV could and should become.

To our collective sorrow, there was no Newton Minow counterpart to warn about the misuse of social-media technology 20 years ago. We live and die each day with the consequences.

But I believe that this month I saw a Newton Minow-like appeal for the future of reality-based geographic awareness. Watch this space for how and why, in the next dispatch, as we paddle our way through the maps and the stories they tell us.

A few more images of Holling Clancy Holling’s canon from the Fallowses’ book collection: