Two days ago I mentioned that Redlands, California, posed a question similar to one we’d encountered in Burlington, Vermont. Namely: what were sizable but standalone Internet-based tech companies doing in these smallish towns? In Redlands’s case, this meant Esri — a leader in the mapping-software industry, and a partner in our “American Futures” project. In Burlington’s, it was Dealer.com.

In the Seattle area or San Francisco or a dozen other big tech-cluster cities, it would seem commonplace to find such firms. But how had they gotten going far from a surrounding tech ecology that would naturally supply all of the supporting elements of a start-up culture, from potential employees to financial or marketing know-how to design studios?

Several readers who themselves work in the tech industry write in with explanations. First, from someone who moved from another part of the world to work in one of today’s dominant tech clusters, the SF Bay area:

Yes, silicon Valley (SV) and its environs (SF) are a tech hub. So if you’re dreaming up a new communication protocol (Twitter), you need to be surrounded by people who can share in your vision of the future — and that means (for the most part) that you have a shared ‘now’, and that’s why Twitter was only going to be built in a tech hub. If you’re building a better search engine (Google) and Yahoo! is just dont the road, then you can strike up a deal to power their search (which funds you) and if you’re surrounded by techies then you have your early adopter users on your doorstep.

Now, if you’re building software for car dealerships then the #1 thing you need to grow is access to car dealerships. Lots of tech folks I know in SF dont even own cars — cars are not top of mind. You’d have the same problem in NYC. On top of that, because a lot of city techies dont care about cars, they’re blind to the opportunity for selling software to car dealerships. On top of all that, as good a business dealer.com is, I suspect the hardest part of building that business is selling to the dealers, not writing the software (that’s still easy to mess up, of course, as proven elsewhere). And I doubt SF car dealers a significantly earlier adopters of tech than anywhere else in the country (I have tried selling tech to them, so I speak from experience 🙂

Good software can be written anywhere that there are smart people. So my mental model is not to ask, “The puzzle, again, is why — and why here?” it’s to ask “Why couldn’t it be built here?”. High-tech spinouts from universities is one possible answer. A need for a cluster of early-tech-adopters (mainly B2C) provides another.

From another person in the California tech industry:

Some thoughts on why you get some clusters and some stand-alone firms far from anyone else. But rarely anything in-between.

As you note, it is now possible to run a high tech company from anywhere, and have employees scattered all over the landscape. For example, the small company I work for [which produces network analysis software] is “headquartered” (i.e the founder and CEO lives) an hour-plus south of Silicon Valley. I am a couple hours northeast of there. I get down there maybe once a year. Our third employee is on the East Coast. The company is over a decade old; later this month we will have our first-ever all hands face-to-face staff meeting.

A company can spring up anywhere, as your examples also prove. But how do you get a cluster?

New start-ups/spin-offs frequently happen because someone wants to do something new and different, and can’t persuade his management to go for it. But for that to happen, he has to have been where he can talk casually with others in the same field. And growing will generally require recruiting from what is essentially a single local pool of talent: the base company. (Recruiting can also be done via networks built at professional conferences. But it’s harder than recruiting over lunch or at the park.) That makes getting a second company going very difficult.

As a result, you can get a stand-alone company anywhere. It’s unlikely, but it can happen. However to get a cluster, you have to somehow get a second (and preferably a third) company in the same area, before additional companies can be started (relatively!) easily. Essentially, that means repeating the original process for starting a stand-alone company. Obviously that’s do-able; stand-alones do get started. But new stand-lones don’t happen often — which means the odds of it chancing to happen multiple times in the same area are really, really low. And only when you get lucky 2-3 times in one area do you have the conditions which will allow a cluster to blossom.

And one more explanation:

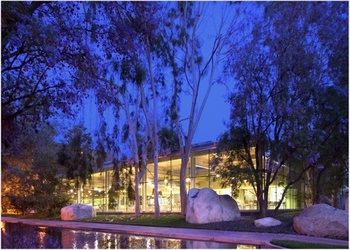

I have to assume your question “Why here?” regarding Esri was rhetorical. It was pretty obvious to me why – because they could. They loved the town, figured others would too, and they succeeded there.

This is really an interesting connundrum. You (and others) have accurately written about the importance of a support system (probably more properly “supply chain”) as being essential to a region’s large scale success, esp in modern manufacturing. It would be incredibly difficult (though not impossible) to open an electronics assembly plant in some random town in America, because it’s so much easier, cheaper, and faster (by most measures) to do so in China.

But as Esri has shown, and Dealer.com as well, if the founder is dedicated to a place, is willing to forgo some, or even most of the easy money, and the location has an appeal that is understood by people other than the founder, then success can happen. It won’t be as fast, or as profitable, but those aren’t everybody’s measure.