A few days ago, I wrote a piece here as part of the American Futures series, taking a look at the Maine Maritime Academy (MMA), a college I had heard good things about. Wanting to learn more about it, I traveled to Castine, Maine, did a day of interviews and touring, and came away impressed by what I saw. (Photo above is of MMA student center.)

Within several hours of when the piece went up on the Atlantic’s website, with the subhead “How a school you’ve (probably) never heard of is preparing students for good jobs,” someone unknown to me, a dean of students (and politics professor) at a west-coast liberal-arts college (okay, let’s just say it: Pomona College) opined on Twitter, acknowledging the piece and dismissing MMA as providing “vocational not broad-based education.”

Taking umbrage at her view, which struck me as narrow and uninformed, I tweeted back: “Not vocational. Just specialized, which far more colleges should try to be.”

Soon her reply came back through the Twittersphere, offering her view of a broad-based education and, I presume, distinguishing that from what she assumes students do not get at institutions that are not liberal-arts colleges: “Discovery, empathy, adaptability is goal of broad-based education, prepares students for life, learning & jobs known & unknown.”

Holy cow. Now my blood pressure was rising, and I didn’t even have a dog in this fight. I didn’t go to MMA; I just wrote about it. But I resented – on behalf of Maine Maritime Academy and its students and faculty, past and present – the smug, arrogant condescension of her reply.

I tweeted back: “And what would make you think those things are foreign to MMA?”

Apparently the good dean had had enough of me, because the tweet-stream went silent and I heard from her nevermore.

But the next day, I received an email from a 1994 graduate of Maine Maritime, complimenting me on the piece about his alma mater (that’s MMA’s Dismuskes Hall, pictured above), but also gently taking me to task:

I recently read your article in The Atlantic about MMA and I felt compelled to reply. I am a 1994 alumnus of the academy and enjoyed my 4 years there in the Nautical Science major (“Deck”) and benefitted greatly from the experience. I was also in the school’s Navy ROTC unit and received a commission as an Ensign and served two tours in the active duty Navy aboard a destroyer and an aircraft carrier, both homeported in Norfolk, VA. I also worked aboard several merchant vessels before coming ashore to get an MBA and work in Finance at Raytheon. So I would say MMA was a great deal for my career development as well.. . .

I feel I must take issue with a certain tone I detected in your article. While countless Maine residents have benefitted greatly from the college, going on to pursue incredibly lucrative careers, MMA exists as more than just a vocational training facility. This is a four-year accredited college, with programs for all levels of academic degrees, as well as an extensive research facility. . . . MMA is more than just a vo-tech [school] for impoverished Mainers, it’s an industry-leading bastion of academia for the world-encompassing maritime industry. The institution may be new to you and most of mainstream America, but, since 1941, MMA has been well recognized by Navy and Merchant Marine officers, oceanographers, scientists, and other professionals connected to the sea and all its facets.

So, now I had reactions of two different kinds, both with vocational education as their point of reference. The dean/prof was dismissive of MMA, slotting it into some kind of voc-ed category in her head. The MMA-grad-former-mariner-now-finance-guy was apparently worried that my piece gave the world the wrong impression of MMA: people might think it’s a voc-ed institution!

All this led me to two lines of thought. First, I should correct any impression I unintentionally gave that Maine Maritime is a vocational school. It is not. As my email correspondent notes, it is a fully accredited, four-year college that offers associates, bachelors, and masters degrees in a variety of disciplines and fields. Faculty teach standard liberal-arts courses (writing, art, history, literature, physical and natural sciences, foreign languages, psychology, political science, etc.). Students in various majors have different liberal-arts distributional requirements, but everyone takes a healthy complement of such courses – in addition, of course, to their demanding array of courses required of their major. When I studied the course catalog, it boggled my mind how much these students have on their plates. The quarter-system calendar that MMA uses helps a bit with that.

Let’s look, for example, at some of the non-business & logistics courses that students going for the Bachelor of Science in International Business & Logistics must take. First year: Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Composition (Writing), Finite Math, World Geography, Humanities, Calculus for Business. Second year:Contemporary World Politics, Foreign Language (Spanish, French, or German), and one of these: Ocean Science, Physics, or Chemistry. Third year: World Geography II, Humanities II, Contemporary World Politics I. Fourth year: One of each of these: Economics elective, general-education elective, Humanities elective.

Or consider those doing marine engineering. (That’s probably a marine-engineering major working on that diesel engine in the photo above.) In addition to the many required courses in their major – courses like Ship Structure & Stability, Diesel Power I & II, and Power Control Electronics – these students have the following arts-and-sciences requirements as well. First year: Composition, Math, Humanities I (interdisciplinary course looking at “cultural roots of modern global society” through the middle Renaissance), and Technical Physics. Second year: Humanities II (late Renaissance to the present), Technical Physics II, Thermodynamics I. Third year: Chemical Principles and electives in each of these: economics, humanities (which includes foreign languages), history, and psychology. Fourth year: Intro to Environmental Regulations and Ethical Industrial Compliance, and electives in each of these: economics, humanities, history, and psychology.

Students in many of these majors at MMA also have all the additional courses and exams required to meet the Coast Guard’s licensure requirements.

I can’t speak for the dean at Pomona, who (like me) has a PhD in political science, but I know that I would have found those MMA courses more challenging than the ones I had to take en route to my doctorate, which for the record was at Harvard. And when I got my BA at Johns Hopkins in the 1970s, the distributional requirements there were nowhere near as broad as those at MMA.

That brings me to my second line of thought: what is it about professors and administrators in many liberal-arts colleges that leads them to believe the kind of education their institutions provide is somehow superior to, more formative of a good life, than education that is more career-oriented? Even if my Twitter-spondent, had been correct in her view about what MMA is all about, what would make her think that people graduating from places like Pomona are somehow more empathetic and adaptable, more open to discovery, more prepared for “life, learning & jobs known & unknown” than people who graduate from other kinds of institutions?

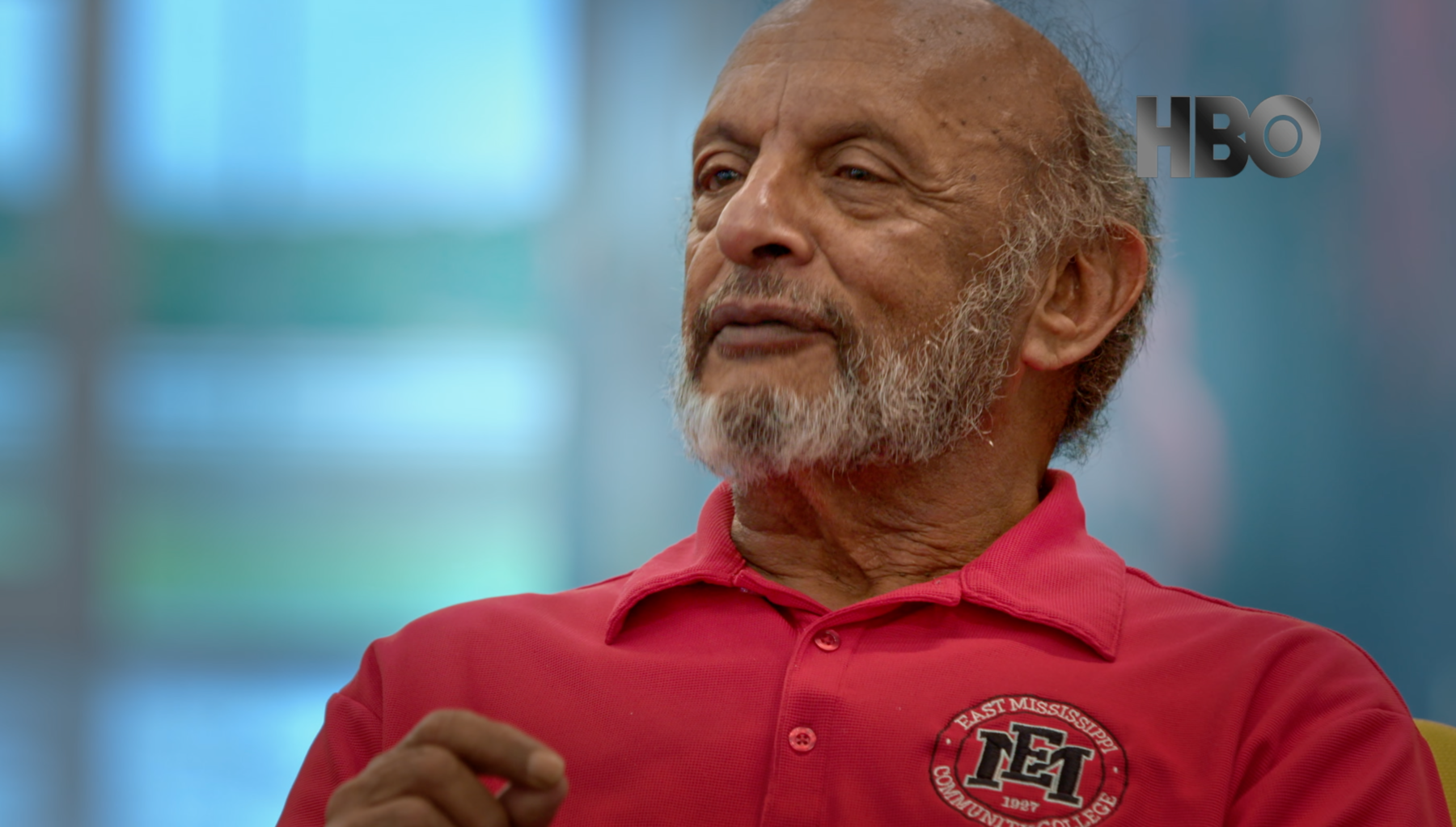

Do empathy, adaptability, and other desirable characteristics emerge only from being a student at places like Pomona, Macalester, Williams, or (to name some of MMA’s competitors in Maine) Colby, Bowdoin, and Bates? Of course not. (Those are a couple of empathetic, adaptable MMA students in the photo above.)

Should we assume that people who go to the Coast Guard Academy, the Colorado School of Mines, the Rhode Island School of Design, the Fashion Institute of Technology (or scores upon scores of other places) are somehow more narrow-minded people? Less adaptable? Less open to discovery? Less prepared for “jobs unknown” than a your standard small-liberal-arts school graduates? Oh, please.

This is a big topic that I want to think about and write about some more. I’d appreciate your views. Write to me at the address below. I’m laying down a marker here, planning to come back to this later.

Thinking about this yesterday, I wrote to a friend I’ve known for over forty years, a professor at Connecticut College, a liberal-arts bastion if there ever was one. Telling him about my Twitter-spondent, I wrote: “I wonder what makes some people at liberal-arts colleges so dismissive of, and condescending toward, institutions that actually train people for careers.”

He responded with this:

Our faculty is now going through one of those reconsiderations of the “general education” scheme. In the committee’s draft of the “guiding principles” was something about “Intellectual and creative skills.” A bunch of people objected to the word “skills.” We’re a liberal arts college, they reasoned, we don’t teach skills. One person argued that teaching “skills” would implicate us in the depredations of capitalism. Skills is now out. The new word is “competencies.” No one is happy with it.

Good lord. Give me the Maine Maritime Academy any day.