Jon Bullock was the principal of Redmond High School, in Redmond, Oregon, when he sat down at his kitchen table with colleagues eight years ago to hatch the beginning of an idea for what would become Redmond Proficiency Academy (RPA).

Bullock was a product of public schools and a strong believer in them. They had worked for him, he told me recently, rattling off the names of four of his early public school teachers in his small lumber mill hometown of Roseburg, Oregon. He described how those teachers changed his life and propelled him toward the dreams of college and a professional career.

But, Bullock continued, with obvious discomfort at saying it, despite his belief in public schools and admiration for the people who pour their efforts into them, he had come to believe they are not designed for all children. In 10 years of public school teaching and administration, he explained, he had seen a model of education in which swaths of students were not thriving.

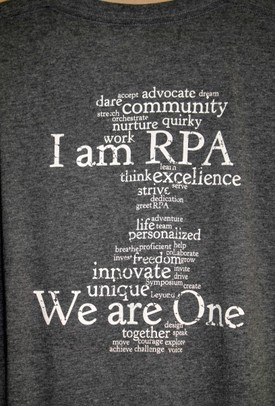

Not thriving is a broad term. Applied to the 800 RPA students, it covers many definitions. There are very smart, talented kids who are not “enriched” by a traditional school environment. Some students are under-challenged or just bored; others are at high risk of dropping out. And there are others who just need a personal pace, to slow down and take more time to show their learning, or to accelerate to stay engaged.

Bullock and his kitchen-table colleagues wanted to build a program that was loose enough to encourage each student to work in their own way to best suit their own learning. This means that students have great liberty to choose the classes they want, even to show up at class or not, to find a groove of learning they’re comfortable with, and to have their success be measured in terms of proficiency or mastery for the content and skills.

Bullock is now the Executive Director of RPA, and he often speaks about the school on his weekly podcasts.

RPA believes that when students take responsibility and “ownership” of the process and content of their education, they are more likely to succeed.

Of course there are requirements to meet before students can graduate. And there is a steep learning curve, just like there is for college students, when they discover that not attending class can have consequences.

There are also safety nets built into the system, including January and June terms, which offer a chance to make up uncompleted work, but also offer the opportunity to pursue some of the many electives the school offers. These range from wilderness preparedness and “remote first aid,” to the science of breadmaking.

The magic underlying this kind of education—and this should come as no surprise as it is pretty much the magic in all education—is the teachers. The word I heard a lot around RPA to describe the teachers is passion. Bullock looks for teachers with passion for their subjects or even more broadly for their lives, and who can translate that passion into a love of learning for their students.

So how does this work? Teachers at RPA have a tremendous amount of flexibility to design their courses. For example, an ex-policeman teaches history through the lens of his passion, which is the evolution of mobs and gangs in the U.S.; his class is called “mobology.”

We got a further taste of RPA’s culture when we went to a show that was “of and by students” at RPA and other local schools. It was held in the historic Tower Theatre in downtown Bend, Oregon, just down the road from Redmond. The show was billed as a production “where TEDx meets teens.” Two of the performers, one a teacher and one a student, gave us a sense of what passionate teaching looks like and how passion translates to students.

One of the RPA teachers, Brandy Berlin, a humanities teacher and professional yoga instructor, engaged the entire theater audience in a mini yoga session, to demonstrate how she engages her class. She says that she uses yoga as part of the students’ “social and emotional education,” something she says they desperately need. She asks them to sweat, breathe, laugh, and even cry. The audience, from students to grandparents, seemed understandably reluctant at first, but by the end of her demo was breathing as one, eyes closed, sitting with perfect posture in theatre seats, and I would say, transported in the moment.

Later, Wyatt Carrell, a Bend High School student with natural stage presence, showed masterful magic skills in making things disappear, appear, move, and change, and talked about his lifelong love of magic. He left the audience with no doubt that he had become a happy, skilled, and successful young man already. Here is a video of his performance at TEDxBend earlier this year:

The hardest part for me to understand about RPA is the final step, measuring a student’s proficiency. What does it mean to “measure proficiency?” Without tests, how do you tell if a student has mastered material, especially in a class like English or history?

I talked with George Hegarty, a humanities teacher with over 15 years of experience in a variety of high schools before he came to RPA three years ago. In explaining how a young student might reach proficiency and what that says about a student’s ability to learn, he emailed this example:

Students who struggle with their ability to construct thesis-based arguments about a novel, poem, or play in an English class have taken walks with their teachers and shared their ideas and analyses of the texts while the teacher took notes. The teacher, then, sits down with the students and helps them see the structured nature of their thinking, and helps them convert the notes into an outline for a paper.

This process highlights that education follows a growth trajectory rather than a “one and done” pass or fail mentality, and we have found that it encourages … students to immerse themselves in particular subject areas rather than simply “survive” Humanities classes.

I commented that this kind of teaching sounded like it involved more individual attention than could be done in traditional public schools. He replied, with a small chuckle, if it would be possible to say it took about 10,000 percent more individual attention.

During our travels around the country with American Futures, I have by now seen many different kinds of schools with many different visions and styles. From rural high schools in the desert and the farmland, to public boarding schools focused on high end humanities or sciences; skill-tracked schools from which students graduate with job-ready skills in high-end trades like nursing or mechanics; and schools where one-by-one kids are plucked out of traditional programs and nurtured along paths from certain failure to college track. Yet, just when I thought I had about seen it all, I ran into yet another model, the RPA.