When David Harrison became president of Columbus State Community College (CSCC) in 2010, the central-Ohio region, though economically healthier than the rest of the state, was still reeling from the effects of the Great Recession. Leveraging the capacities of the large institution he heads, Harrison began assembling a New-Deal-like potage of programs aimed at preparing people for the workforce, closing the skills gap, providing pathways to a debt-free education, and increasing the number of students earning a postsecondary degree or credential.

The recession is over now, even if its effects linger. And the economy in the Columbus region is growing faster now than any other part of Ohio. But the needs CSCC is addressing persist. “We’re trying to make sure there’s a collective impact that is greater and more long-lasting than any particular time period or any individual project,” Harrison told me. “What we’ve been able to do the last couple of years is connect the college to the community—and vice versa—in really deep ways, so that while we’re trying to advance the college, we’re also trying to address the most pressing needs of the region.”

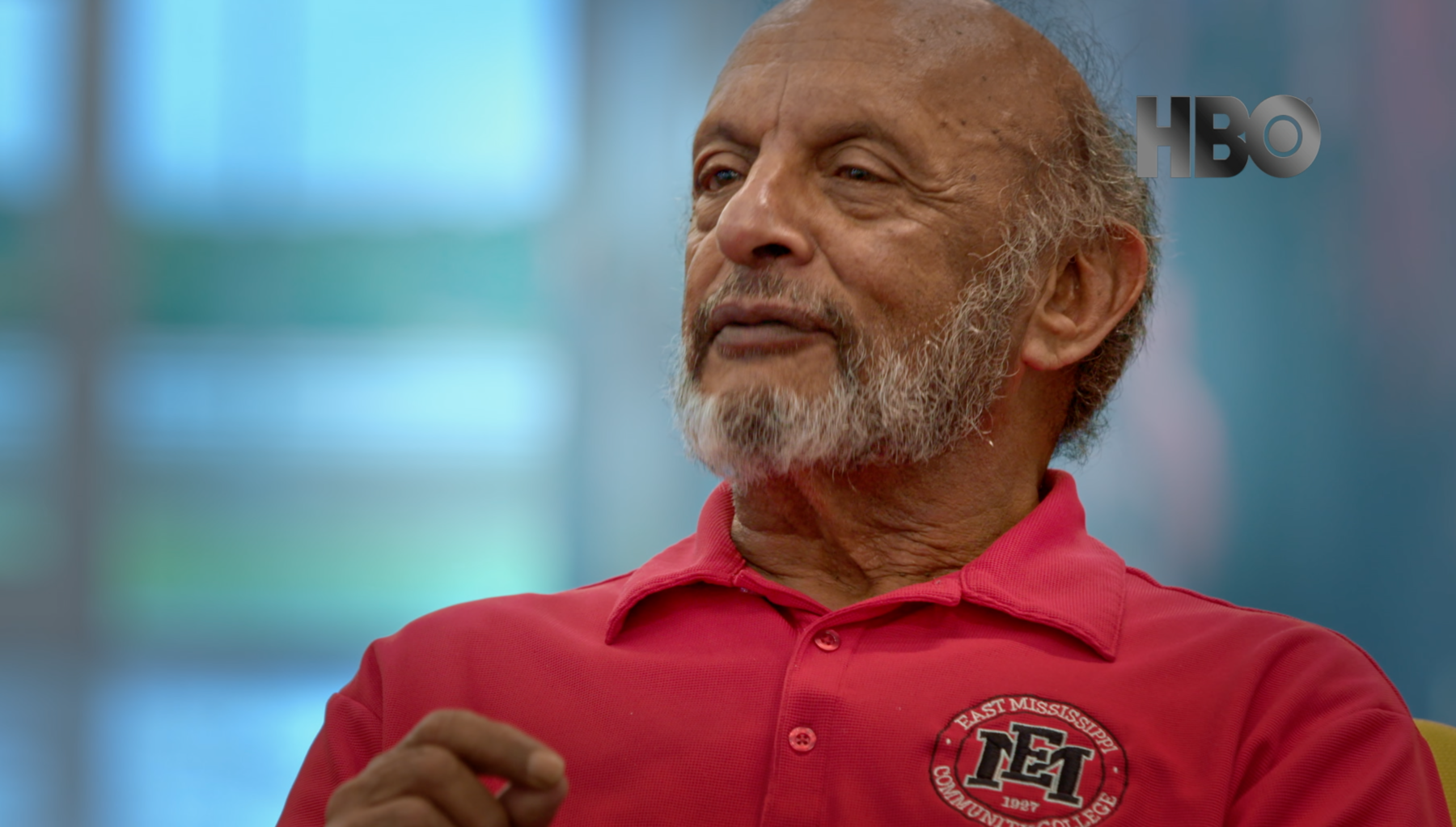

Those two sentences from my hour-long interview with Harrison in September nicely capture a sense of how this education leader sees what he is trying to do in Ohio’s capital city and its surrounding region: addressing the needs of the community and aiming to have a lasting impact. I was in Columbus with Deb and James Fallows to report for the American Futures project, and I kept hearing people mention Columbus State and its president in admiring ways. I wanted to find out more.

Before speaking with Harrison, I met first with five of his top staff and was quickly overwhelmed by the flurry of programs and initiatives they were describing to me. The names and descriptions were coming too fast for me to digest immediately: the Central Ohio Compact, FastPath, New Skills at Work, Preferred Pathways, Credits Count, and so on. Fortunately, I’ve since then had time to make sense of all these programs; unfortunately, the landscape of initiatives is too rich and complex for me to describe in detail here. But I’ll try to give you the flavor of it.

Harrison assumed the presidency of CSCC having most recently served as Vice Provost at the University of Central Florida, where he had successfully established a program that guarantees the opportunity for a bachelor’s degree for graduates of partner community colleges. Within a year of arriving at CSCC, Harrison had put together a similar program, called Preferred Pathways, that guarantees admission for CSCC graduates to The Ohio State University. Students do their first two years of college work at CSCC and then move on to OSU for the last two years.

The program got a lot of positive attention, and that enabled Harrison and CSCC to work out similar arrangements with six other colleges and universities in the region. All this is making a real difference in helping to provide an affordable education for many, as well as keeping those people and their talents in the region. Harrison said, with clear delight, “We now have a few cycles under our belt, and we’re finding that our students are doing really well—performing at a high level, graduating on time or even early. So we’re building a track record that is a real win for each institution, but also a win for students and families.”

That success set the stage for what is arguably Harrison’s premier achievement, something called the Central Ohio Compact, which is worth describing in some detail, starting with its genesis.

As he was getting the Preferred Pathways program put together, Harrison said, he used his “new-guy excuse” to go around and interview a lot of area school superintendents. He found a common refrain in those conversations had to do with “the high—and growing—levels of remediation required with students who were graduating from high school and coming to college but weren’t really ready to do college-level work.” Another recurring issue involved the misalignment of curricula with business needs.

Finding over time that he was having much the same conversation both with school superintendents and with other college presidents, Harrison finally said to a number of them, “Look, we all seem to be interested in the same problems. It seems worth it for all of us to get together and figure out what we can do about this together.” So, in 2011, CSCC hosted 150 people—college presidents, school superintendents, and various of their staff members—for the first regional summit on college completion and career success.

But then, in early 2012, Harrison was in Washington, D.C., for a meeting that Senator Sherrod Brown hosts each year with the presidents of all of Ohio’s colleges and universities, public and private. Harrison said: “One of the speakers there was Jamie Merisotis, the President and CEO of the Lumina Foundation, and he was talking about Lumina’s 60 percent goal,” which is a nationwide effort by the foundation to increase the proportion of Americans with high-quality college degrees, certificates, or other credentials to 60 percent by 2025.

Harrison knew right away that in the Lumina Foundation’s objective, he had found both the goal and the narrative hook around which to build his regional initiative. “I brought that back to the Central Ohio steering committee, and we all said, ‘This is the galvanizing goal; this is what we’re trying to achieve.’ And we adopted that goal.”

Adopting that goal meant taking on a big responsibility: Harrison and his team understood that to reach the 60 percent goal, CSCC would have to be the key player. “CSCC is the only open-access institution in the region,” Harrison told me, and that makes it “the front door to higher education for central Ohio.”

Moreover, the leadership team at CSCC understood that meeting the 60 percent goal would require a complex, multi-pronged approach: expanding dual-enrollment programs; improving the alignment of secondary and post-secondary curricula with workforce demands; meeting the needs of working adults who have some college work behind them but no degree; and providing training and support to low-income, unemployed, and underemployed adults in the Columbus area.

Efforts to make progress along all those pathways have spawned, or been aided by, other new partnerships, initiatives, and programs. Many of them have come about because, as Harrison explained to me, “There’s a strong collaborative spirit in Columbus,” which is something we had heard many times before about this city. People at the top of big, resourceful organizations get things done with a conversation and a handshake. “It’s not the kind of thing you could write a manual about,” Harrison said with a quiet laugh “partly because it’s all so relationship driven.” Here’s just a sampling of the program partnerships that are helping CSCC in its mission.

— American Electric Power (AEP), one of the region’s top employers, is donating $5 million over 5 years to fund Credits Count, a workforce-education and training program that will help some 3,000 students from five high schools in the Columbus City Schools system earn college credit and career certifications. It started this fall at the city’s West High School. (See explanatory video here.) The program provides work experience in STEM-related career fields. It’s modeled after a program that CSCC earlier had established with Reynoldsburg High School, under which the college had space at the high school to run a regional learning center. Through dual enrollment, high school students are able to earn college credits through coursework that prepares them for college and jobs, while saving their families money. The program has been growing steadily.

— As part of its leadership role in the Central Ohio Compact, CSCC was deep into discussions, both internally and externally, about how to strengthen career pathways linking high schools, community colleges, and employers. The goal is to increase the number of kids who finish high school and get a postsecondary credential that would help them find a job. Harrison told me that after hearing about the CSCC effort at a college-sponsored event, Jeff Lyttle, an executive at JPMorgan Chase, approached Harrison and said “Consider us a partner.” That led to JPMorgan Chase investing $2.5 million in Columbus as part of its New Skills at Work initiative that’s aimed at training people with the skills that employers need.

“That idea really resonated with me,” Harrison told me. “Because I’ve been involved in urban-workforce and economic development, I know one of the problems is that if the jobs aren’t where the people are, transportation becomes an issue. So, an explicit strategy where a hospital wanted to hire more neighbors really appealed to me.”

Then in January of 2014, Columbus Mayor Michael Coleman asked David Harrison to meet with him to talk about workforce development and income inequality. The two talked about how to help people who are unemployed or underemployed but “are close, just needing a little help to get on the ‘on-ramp’ to a job.” As they talked, the two became more focused on the idea of using Nationwide Children’s Hospital as a demonstration site. By the time the mayor gave his annual State of the City address the following month, the program had a name—FastPath—and the mayor committed at least $1.5 million from the city budget to help jumpstart and support the NCH-CSCC partnership.

Fewer than nine months later, CSCC is heavily involved with NCH and the people in the hospital’s adjacent community, having quickly established a program that provides services along three different tracks: supplying remediation work in math and reading to kids aged 9 through 14; getting underemployed adults into short-term training programs to earn certificates in patient care, food services, and building services; and helping CSCC students from that neighborhood get supplemental training to prepare them for jobs at NCH. And across all those tracks, CSCC provides supplemental training and support in areas like employability skills, organization and time management, financial literacy, computer basics, and so on.

In short, through this program, CSCC is involved in a broad spectrum of services—social as well as educational—that considerably stretch what many might consider the boundaries of a college’s mission, even a community college’s mission. No wonder Harrison’s top staff seemed busy and hard-pressed when I met with them. These people have a lot on their plate.

When I commented to David Harrison that all of this adds up to a very ambitious agenda, he agreed. He went on to say that while in some ways these are separate and distinct initiatives, because of different funders and so on, “in an important way it’s all the same work.” And that’s when he said, “We’re trying to make sure there’s a collective impact that is greater and more long-lasting than any particular time period or any individual project.”

You can hear the optimism and determination that infuse this man’s thinking. “It’s not a responsibility we back away from; it’s a responsibility we embrace. These aren’t side programs, but are the core of what a great community college does. And building a relationship with the community is central to what a great community college should be doing,” Harrison said. He’s right.