A commitment to place-focused economic policies to close economic opportunity divides between various geographies to help hold societies together has a long history in Europe. For decades, cohesion policies have invested in economically struggling or transitioning regions in nations of the European Union (as well as the United Kingdom before Brexit).

These policies aim to realize a more equitable spread of economic opportunity, a glue that binds societies together. In Germany, the managing of a long-term structural adjustment in Ruhr, the iconic former coal and steel region, and the unifying of both the polity and the economy of former West and East Germany serve as an example of relative success at evening out the geography of economic opportunity.

The United States is finally paying mind to closing these divides, making unprecedented investments in place-based industrial policy and more inclusive economic growth – in part driven by national political unrest and anti-democratic populist movements in declining heartland regions. Similarly, ever since residents of neglected, left-behind, economically distressed mill, manufacturing, and mining communities in England’s North shocked the world by driving Brexit, both the in-power Conservative government and opposition Labour party share an agenda to effectively “level-up” in-decline regions of the U.K.

With this great convergence on both sides of the Atlantic around the urgent need to diminish geographic economic disparities and opportunity gaps — particularly those between thriving global city regions and struggling communities in industrial heartlands – there are growing efforts to learn from each other. Doing so will help inform how to rejuvenate once economically mighty but now ailing industrial communities. When this is done successfully it works to take the steam out of anti-democratic populist movements that pose imminent challenges to the stability of our political order on both sides of the Atlantic.

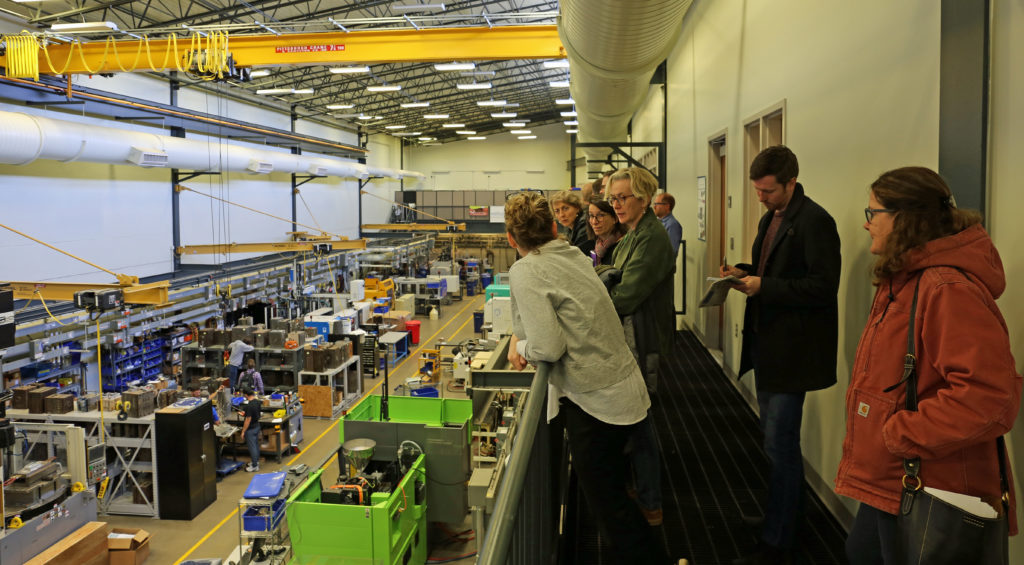

This kind of transatlantic exchange of ideas was the point of a recent study tour of Midwest industrial communities. The tour brought international economic change practitioners to the region.

Many Midwest communities have a similar economic development trajectory and storyline to industrial regions in the U.K and Europe. Some have been successful in turning an economic corner. Others are in the middle of navigating difficult economic transitions from the factory economy of yesteryear to today’s globalized, knowledge, and technology-driven one.

Until the recent round of federal place-focused investments as part of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP), Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), CHIPS and Science Act, and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Midwestern communities have largely been on their own, charting their own economic renewal visions and raising the resources to execute through local civic, business, government, and philanthropic collaborations. The successes and failures of European regional economic structural change efforts and cohesion policy has been extensively documented, but local-level economic renewal efforts in the U.S.—which are numerous and profound—have been largely underreported on with communities disconnected from each other (apart from efforts like that of the Our Towns Civic Foundation and other organizations focused on resident-level responses that work to illuminate the positive and creative innovation and community renewal efforts happening outside the view of the Beltway, and popping up all around the country).

That is why it was so instructive for me to travel with the European visitors from Pittsburgh in the East to Milwaukee in the West over 10 days in November 2022.

Then and there, I learned firsthand about the dynamics of economic transformation in the Midwest’s heartland communities. These communities are remarkably similar to the homes of the European study tour participants in the North of England and France, Germany’s Ruhr, Belgium’s Wallonia region, and Italy’s Piedmont.

Ten economic change practitioners and policy-shapers from industrial regions in the U.K., France, Belgium, Germany, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the European Commission experienced a journey of discovery across America’s heartland. (You can see the roster of attendees and review their full study tour program and descriptions of communities they visited and the people they met here, and see a fuller collection of photos from Michael Schwarze-Rodrian here.)

There were a lot of surprises for our guests. Some include seeing:

— Entrepreneurial universities that rapidly develop new technologies and talent to support start-ups and more competitive local businesses.

— Community economic development strategy-making and leadership coming from the business community in one region, government and political leaders in another, third-sector and civil society in a third.

— Communities fiercely cleaved by strictly enforced racial boundaries.

— That there was still lots of manufacturing.

— And not all America was a “Silicon Valley.”

These were among the novel-to-them features of Midwest communities observed by study tour participants, an exchange organized through our Transforming Industrial Heartland Regions Initiative:

— Pittsburgh: they saw the impact of powerhouse universities, like Carnegie Mellon and University of Pittsburgh, in building a new high-tech economy, and massive former steel-making complexes remade as centers of national manufacturing innovation and R&D or as heritage sites.

— Erie, Pennsylvania: they marveled at undergraduate students at Penn State Behrend and Gannon University working for technology startups, building and prototyping new technologies, earning new patents, and getting paid. They also saw community leadership and global engagement being provided by civic institution and community convenor: the Jefferson Educational Society. They even participated in a panel discussion as part of the think tank’s Global Summit.

— Cleveland: they viewed new technological innovations coming out of universities and medical research complexes, like the Cleveland Clinic, being turned into new commercial products and new companies at a dizzying pace; public-private partnerships helping Cleveland’s large-scale auto-related industry pivot to the opportunities offered by new electric vehicle production. They were awed by grandeur of refurbished Opera and Theater houses built with vast wealth generated by the 19th and 20 century industries, newly anchoring an arts and cultural district downtown.

— Detroit: they toured one of the nation’s largest industrial waterfronts repurposed for use and enjoyment with trails, parks, heritage and cultural venues along the Detroit River, and an urban market district bursting with life, welcoming to rich and poor, and igniting new neighborhood reclamation efforts. They witnessed the grand historic Michigan rail depot, abandoned for years, and an icon of Detroit’s infamous “Ruin Porn,” now being remade as Ford Motor Company’s world center for new mobility engineering and innovation, hiring thousands of new workers and rehabilitating hollowed-out neighborhoods.

— Grand Rapids, Michigan: they heard the story of one of region’s most successful, long-term, regional, civic-business-political leader partnership efforts to recover from manufacturing job loss, rejuvenate an urban core, and diversify an economy once dominated by its signature furniture industry.

— Chicago: they saw the fruits of years of investments in the downtown makeover that helped turn Chicago into a truly global city, as well as new efforts to prioritize development in broad swaths of urban neighborhoods, segregated by race and hollowed out by deindustrialization.

— Milwaukee, Wisconsin: they toured an emerging global water technology center, and saw the Lake Michigan harborfront remade – the conversion of empty factories into affordable housing and craft beer manufacturing. They came to learn of a community having frank discussions about how to nurture racial equity in America’s most segregated city, conversations facilitated by the city’s mayor, who is Black, and business leadership, which is largely white.

The participants were amazed at the energy, entrepreneurial spirit, and creative cross boundary partnership-building at work in the places they visited. Leaders and community coming together to plot and manage economic renewal.

In Europe, they call it “managing economic structural change.” In the U.S., we refer to it as place-based economic development. Europeans speak about “smart specialization;” Americans talk about innovation in emerging sectors. They talk about “Just transition;” we speak of inclusive growth.

Our language and dialects may differ, but we are discussing the same ideas and aspirations. The success of our collective transatlantic work to accelerate economic change in industrial heartland regions at home and with allies in Europe has huge implications for the future of our society, our democracies, and the health of our alliances.

And we can learn a lot from each other and help each other in the doing of it. It’s time we listen and connect.