At the moment I am writing from Burlington, Vermont, where my wife and I have been for the past few days and will return again next week.

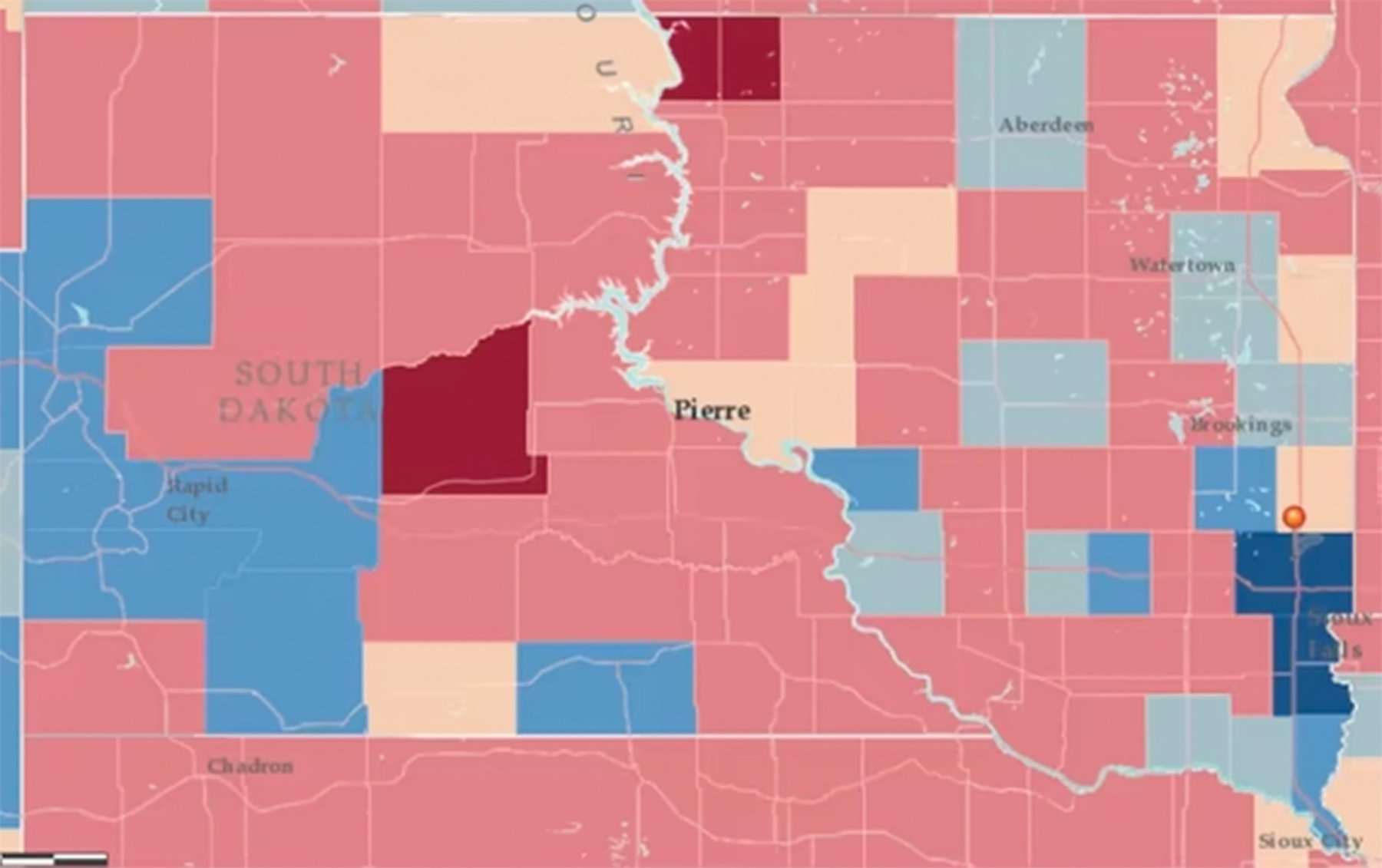

In a lot of immediately apparent ways, Burlington seems a complete contrast with some of our previous extended stops, like Sioux Falls, South Dakota, or Holland, Michigan. Just one easy example in each case: The prevailing political and cultural tone of Holland, as mentioned before, is strongly Christian, Dutch, and conservative. That’s not how things run in Burlington (see right)—where now-U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders got his start as mayor, and where power on the city council is split between Democrats and Progressive party members. Current lineup: 7 Democrats, 4 Progressives, 2 Independents, 1 Republican.

For an easy contrast with Sioux Falls, Burlington is a town of 40,000+ people that includes a sizable campus, the University of Vermont’s, but that does not include a single McDonald’s outlet. Every time someone here has pointed out that the one former McDonald’s outlet in Burlington has now been converted to the (wonderful) Farmhouse craft brewery and asked if we’d like to give its product line a try, we have said, Yes, that sounds like a good idea.

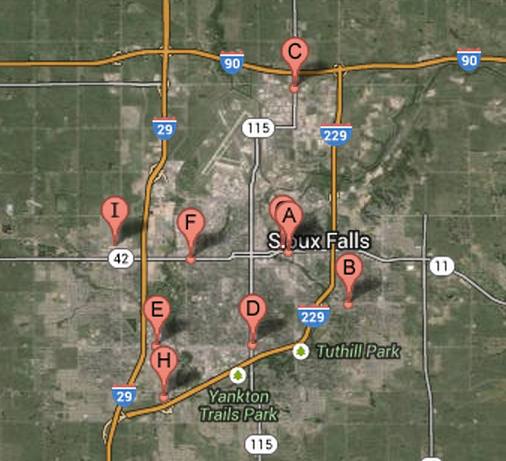

Sioux Falls is much bigger than Burlington, but it has an incomparably larger number of McDonald’s (see above)—and Subway, Sonic, Taco Bell, Perkins, Olive Garden, Domino’s, and any of the other mass-market, nationally standardized eating, shopping, lodging, car-washing, payday-loan-giving establishments you might see along freeways anywhere. WalMart and Sam’s Club, Michael’s and Lowes, big box stores of any kind—you will find them around the periphery of Sioux Falls, including in what has become the state’s largest tourist draw, the Empire Shopping Mall.

You might have guessed that I am setting up a “but beneath the contrasts, we find surprising similarities …” pivot, and in due course that will certainly come, involving elements of these cities’ economic resilience and cultural strength. But for today I want to use this latter contrast—big-box franchise retail relatively scarce in Burlington, and super-abundant in Sioux Falls—to mention an important element of the economic and cultural identity of Sioux Falls.

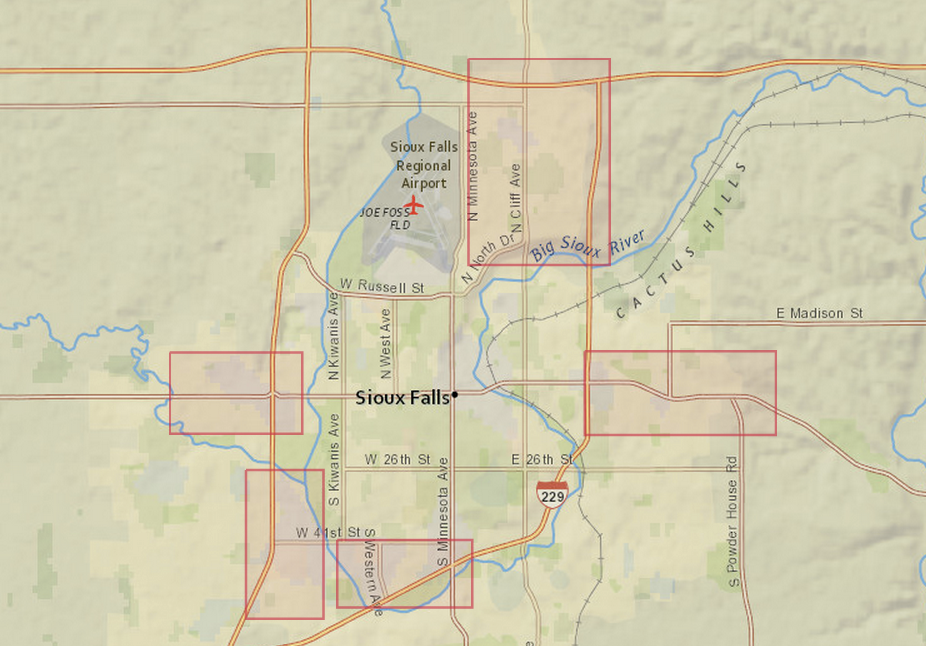

I mentioned to a friend in Sioux Falls that the city seemed “over-retailed.” Who could support all these giant shopping malls? The big retail zones on the four frontiers of the city, as shown in the red boxes on this map (mentioned earlier), each seemed to be ambitious enough for a city on its own.

“You’ll notice,” this man said, “that we’re also over-lawyered, and over-banked, and over-doctored and -hospitalized, and over-serviced in any way you want to name.” The reason, he said, was the city’s emergence over the past generation as the economic capital of the region as a whole. If you lived within a couple-hundred mile radius and needed to do back-to-school or special shopping, get a medical checkup, or look for entertainment, you were less likely to look in your own tiny Dakota town and more likely to go into Sioux Falls. The city’s economic-development leaders refer to this as its “Fringe City” advantage, as the nearest big-ish city for the surrounding rural areas in both Dakotas, Iowa, southern Minnesota, and northern Nebraska. The next level of bigger cities are “the Cities,” Minneapolis and St. Paul, to the east, Denver to the west, and Dallas to the south, all some distance away.

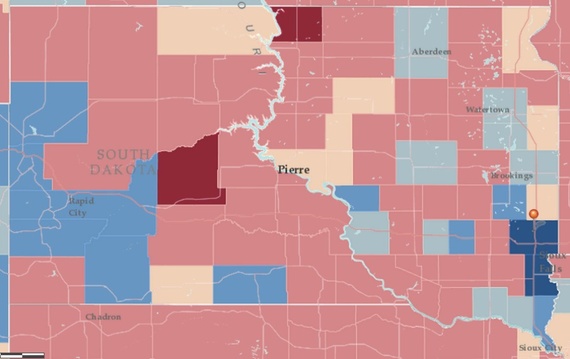

The economic effects of this role for Sioux Falls are obvious: drawing on the prairie hinterland gives increasing strength to its retail, entertainment, service, and professional-medical-educational sector. The effects through the plains and prairie area also match what Americans have heard for years: the steady movement of people off farms and away from small towns, and into bigger cities. South Dakota has a huge number of counties for a relatively small number of people (66 counties,well under 1 million people), and decade by decade most of its counties have decreased in population. Here’s the projection for the few years ahead. Blue means increase, red means decrease, and basically this means that most of the state is emptying out and going (mainly) to Sioux Falls and also to Rapid City and its surroundings.

How does this look and feel when you’re in a city that is becoming a regional capital? A few illustrations, building to the one we found most important:

- We stayed in a bargain “extended-stay suites” motel right near the Empire Mall. The place was jammed on each of our visits: during the week, mainly with business visitors, but starting Thursday nights and through the weekend mainly with families from farms and tiny towns who had come for a weekend to shop and see the city. Or, for medical treatment at the area’s two big competing (both non-profit) health care systems, Sanford and Avera.

- When we talked with college students at Augustana, the private Lutheran college, or the public universities, the most typical story was: I am from Spearfish [Mitchell, Watertown, Brookings, Huron, Pierre, Basalt, a farm 20 miles from the nearest town] and I’ve made it out of there for college.

- Similarly we heard from college-age people in Sioux Falls: Back in my town, the public school is shrinking or being consolidated [so we go to a regional school], the local grocery store is closing [because the owner got too old] so we take big shopping trips, the Post Office is closing, it’s only my parents [my uncle, my grandparents, our old neighbors] who are back there, because it doesn’t take much manpower to run the farm.

- We talked with a dozen students who had just graduated from a Sioux Falls public high school and were all headed off to college—most in the immediate area, one to the University of Nebraska, another to a small private school farther away. We asked how many of them had lived on a farm, and one or two hands went up. How many had immediate relatives still on farms or small farming towns? All but one person.

Which brings me to the cultural/political point for the day. Every city that is “hot” or successful in some way attracts people from someplace else. That’s one of the ways you know it’s hot. Our biggest, hottest, international magnet cities—LA and SF, NY and DC, Boston and Chicago and Miami and Seattle and whatever you’d add to the list— draw people from around the country and the world. And if someone from South Dakota shows up at a research lab in Boston or an app-development team in the Bay Area or a TV show in LA, the standard coastal narrative would be that the person had “made it” out of the heartland and into the big time. Most obvious South Dakota example of making it nationally in this sense: Tom Brokaw, from Yankton.

But to a very noticeable degree, the dominant tone we heard in Sioux Falls was of people who feel that they have “made it” precisely by getting to the state’s biggest city from the farms or tiny hamlets where they grew up. Many people we met talked about Sioux Falls as occupying a sweet spot: big enough to offer most of what is attractive about very large cities (shopping, medical care, entertainment, and increasingly rich food-and-drink life) but small enough to be manageable, inexpensive, and—a word we often heard—”safe.”

In sum: the big-box malls all around Sioux Falls are a disappointingly familiar part of its look, versus the more home-grown look of its restored and revived downtown. But those malls also symbolize its role in the region, which in turn gives so many people there a sense of being in the right place at the right time.