Earlier this month my wife and I spent about a week, in two visits, in the little town of St. Marys, Georgia, on the southernmost coast of Georgia just north of Florida and just east of the Okefenokee Swamp. It’s a beautiful and historic town, which is best known either as the jumping-off point for visits to adjoining Cumberland Island National Seashore or for the enormous Kings Bay naval base, which is the East Coast home of U.S. Navy’s nuclear-missile submarine fleet and which is the largest employer in the area.

St. Marys is known to our family for its complicated and often-troubled corporate history, which I described long ago in a book called The Water Lords and which we’ll return to in upcoming posts. But it also highlights an aspect of American education which we’ve encountered repeatedly in our travels around the country and is well illustrated by the school shown above, Camden County High School, or CCHS from this point on.

CCHS is the only high school in the county, drawing a total of some 2800 students from the cities of Kingsland (where it is located), St. Marys, and Woodbine plus unincorporated areas. Each year’s graduating class is around 600 students. Its size gives it one advantage well-recognized in the area: it is a perennial athletic powerhouse and has won the state football championship three times in the past 10 years. It also has another advantage that I recognized from my own time as a student in a single-high-school community: it creates an enforced region-wide communal experience, across class and race, rather than the separation-by-suburb of many public schools. This part of Georgia has relatively few private or religious schools.

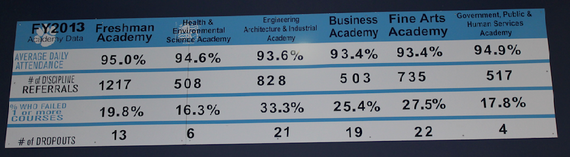

As a matter of statistics, the CCHS student body is more or less like the surrounding area: about one-quarter black, most of the rest white, and small numbers of other ethnic groups (including from Navy-related families). About 40 percent of the students qualify for reduced-price lunch, the main school proxy for income level, and about 60 percent go to post-high school training of any sort. Each year, a small number go away to out-of-state schools, including selective ones. In 2001, only 50.5 percent of the school’s students graduated from high school. Now that is up to 85 percent, a change that Rachel Baldwin, the CCHS Career Instructional specialist who showed us around, attributed mainly to the school’s application of programs from the Southern Regional Education Board. CCHS has the best AP record of high schools in its part of the state.

That’s the background. Now what struck us, which was the very practical-minded and well-supported embrace of what used to be called “vocational education,” and now is called the “career technical” approach.

In practice what this means is dividing a large, sprawling campus and student body into six “academies,” with different emphases. One of them is the Freshman Academy, to get the new students acclimated. (“I don’t know if you’ve seen ninth graders recently,” one person there told us. “But some of them look big and old enough to be parents of some others. It’s a big range, and it helps to have a special place for them.”)

The other five academies each have a “career technical” emphasis. After freshman year, all students enroll in one of the five. While they still take the normal academic-core range of subjects, they also get extensive and seemingly very-well-equipped training in the realities of jobs they might hold.

A few examples:

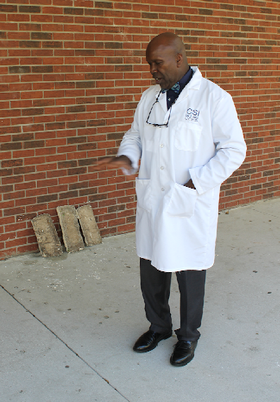

In the “law and justice” curriculum, which is part of the Government and Public

Service Academy, a former Navy-Kings Bay NCIS official named Rich Gamble (right) trains students in conducting mock crime investigations, and preparation for testimony in court.

On the day we were there, he had staged a mock robbery, in which the perp grabbed a cashbox from an office, ran through the hallways, and dumped the box as he was escaping. (The students acting out the scenario wore their white CSI lab coats, so other teachers would know what they were up to.) Then Rich Gamble divided his students into three teams to investigate the crime—making plaster casts of footprints (below), taking evidence, filing reports, preparing a case. “We emphasize a lot of writing,” he said. “I give them issues where they have to defend themselves, in very few words, because courts don’t like you to waste words. Some of these papers are as good as any written by NCIS.”

In the Engineering and Industrial Technology Academy, students design and build doghouses and other structures, which they sell in the community; do welding (and compete in state and national welding competitions); run an auto-repair shop that handles county vehicles; and do extensive electrical work, and other activities I’ll suggest by the photos below. Wood-frame construction:

Inside the wood-and-electric shop:

Masonry:

Welding:

Auto shop:

This same academy also includes computer-aided design and robotics programs, under the direction of Fred Mercier. The houses in the first photo are ones his students had designed and built, sitting on top of a 3D printer they use. The contraption in the second is part of the school’s entry in a national robotics competition.

3D printer above, catapult-throwing arm for robot (with Fred Mercier) below.

(These photos show young men, but that is happenstance of where it was feasible to take pictures. The academies are diversified by gender and race.)

In the Health and Environmental Sciences Academy, students were preparing for certification tests by administering care to dummies—in this case, representing nursing-home patients.

There is more to show, including from the other two academies: Business and Marketing, and Fine Arts. CCHS has an industrial-scale kitchen and catering facility, overseen by a former Navy chef. It has a very large auditorium, where students not only perform plays, dances, and concerts but also learn to build scenery and make costumes. I’m running out of time, and you’ve got the point by now.

Here is why we found this interesting and surprising. Among the non-expert U.S. public, the conventional wisdom about today’s education system is more or less this:

- At the highest levels, it’s very good, though always endangered by budget cuts and other problems;

- At the lower ends, it’s in chronic crisis, for budgetary and other reasons;

- And overall it’s not doing as much as it should to prepare students for practical jobs skills, especially for the significant group who are not going to get four-year college degrees. Sure, the Germans are great at this, with their apprenticeship programs and all. But Americans never take “voc ed” seriously.

I’m not trying now to address all levels of this perception, and one high school doesn’t prove a national trend. But what struck us at Camden County High was its resonance with developments we have seen elsewhere,: schooling explicitly intended to deal with the third issue, serious training for higher-value “technical” jobs. This is theme that John Tierney has previously discussed regarding schools in Maine and Vermont, and Deb Fallows about South Carolina. “Non-college” often serves as a catchall, covering everything from minimum-wage-or-worse food-service jobs, to highly skilled hands-on technical and engineering jobs that may be the next era’s counterpart to the lost paradise of assembly-line jobs that paid a family-living wage in the Fifties and Sixties.

“In the past, we’ve encouraged all kids to go to college, because of the idea that it made the big difference in income levels,” Rachel Baldwin told me on the phone this morning. She then mentioned a recent public radio series on the origins of success, and said: “The recent evidence suggests really goes back to something like ‘grit.’ I think you are more likely to learn grit in one of these technical classes. The plumber who has grit may turn out to be more entrepreneurial and successful than someone with an advanced degree. Our goal has been getting students a skill and a credential that puts them above just the entry-level job, including if they’re using that to pay for college.”

And oh, yes: What the weight room looks like for a state-champion football team.

Thanks to all at Camden County High. And Rachel Baldwin has written in with a closing thought on the career-technical/traditional-academic balance:

As a naval community, Camden County appreciates the phrase “a rising tide raises all ships.” Our AP students at CCHS thrive in Career Technical options (we have more than 20 AP course offerings), along with students who would be considered traditionally “vocational” in the past. Our administration and faculty, believing in “all ships rise,” recognize and provide strong support for both achievement at higher academic levels and meeting the new technical demands of the workplace.