Cities fortunate enough to have a waterfront—along a river, lake, or ocean—know it’s a treasured asset that can be leveraged for the good of the community. But actually figuring out how to do that isn’t easy, in part because of the expense, but also because there’s almost inevitably conflict over the practicalities: Should it be used for recreation? Residences? Office buildings? All those things?

We’ve seen this in the cities visited this past year for the American Futures series. In Burlington, Vermont, for example, the city’s full revitalization stops short of its northern waterfront, in part because of prolonged disagreement about what to do with old properties, particularly the abandoned Moran power plant, along the shore of Lake Champlain. But they’re still working on it. Sioux Falls, South Dakota, has had more success turning Falls Park, along the rocky banks of the Big Sioux River, into a tourist and recreational mecca, a highlight of the city’s ambitious effort at downtown revival.

Lately, we’ve been reporting on our August visit to Allentown, an old industrial city near the eastern edge of Pennsylvania, about 60 miles north of Philadelphia. The Lehigh River snakes through its heart. Like so many other old industrial cities, Allentown and the Lehigh have suffered from the legacy of the past.

Long valued chiefly for its transportation or effluent-discharge uses, the Lehigh has never realized its potential in Allentown as an urban amenity, home to restaurants, apartment and office buildings, shops, and other elements of a lively area. Instead, Allentown’s riverbanks are largely brownfields, now abandoned or undervalued parcels of land that nobody saw value in turning around.

But that’s starting to change in one small area. And it’s doing so rapidly.

Allentown’s Neighborhood Improvement Zone (NIZ), which I described here a couple weeks ago, designated two large parcels of land to spark development—about 80 acres along the western banks of the Lehigh River and smaller portions located strategically at the city’s core. Much of the City Center portion of the NIZ is already pretty far along: In fact, its centerpiece—the PPL Center hockey/performance arena—opened on September 12th with a sold-out concert by The Eagles.

Development of part of the riverfront portion started in July, when crews began demolishing the long-abandoned Lehigh Structural Steel plant that, until it closed in 1992, had operated along the banks of the river for more than 70 years. You can see the commencing of demolition, and the ceremony that preceded it, in this video:

Other buildings being demolished in the former industrial area to make way for the Waterfront development include warehouses for a tire company and a scrap-metal yard.

The plans for the $325 million Waterfront development are ambitious, just like the other efforts to revitalize the core of this long-beaten-down city. By the time the Waterfront is completed in eight to 10 years, the 26-acre mixed-use site will have 610,000 square feet of office space, a mix of upscale dining and retail, and 172 luxury apartments.

There’ll be a half-mile “river walk,” more than a mile of walking and running paths, and two large open-space plazas, all designed to provide unobstructed water views and access to the river itself.

The first phase of the project should be completed by late 2018 and will feature an eight-story building (artist’s rendering above) with 150,000 square feet of office space and 20,000 square feet of street-level stores and restaurants.

Readers who live in bigger cities that have plenty of attractive new mixed-use developments may regard what I’m describing with a yawn and a dismissive “So what?”

But people in Allentown don’t see it this that way. They rightly consider it a big deal. Other than the PPL Center that recently went up a little more than a mile away as part of the redevelopment at the city’s center, nothing of this scale has been attempted in Allentown in decades—and never along the blighted banks of the Lehigh.

development site. (John Tierney)

It says something about how hungry people in this community are for the kind of “live-work-play” area this development promises that the planning stage was free of conflict and controversy. In August, I interviewed Mark Jaindl, whose development company, Jaindl Properties, has partnered for this project with the firm of Dunn Twiggar. Sitting next to his large computer monitor, which offers him constant live, split-screen views of the work currently underway at the waterfront, he explained to me that the support from the community for this project has been very strong. “Unusual, too,” he said, “in that there was not one point of opposition or complaint at any time from the community in the process of considering this proposal.”

Assuming that’s true—and my research hasn’t turned up anything to suggest it’s not—it’s pretty remarkable, especially for a project along a riverbank, with all the environmental issues that involves. But people here recognize that this is a real opportunity to enhance the city’s economic vitality and the quality of life.

The 26-acre area of the Waterfront development currently generates only about $120,000 a year in real-estate taxes for Allentown. Jaindl says that by the time the development is completed, “that number will be $4 million annually.” For a city the size of Allentown, that’s huge.

The businesses, restaurateurs, shopkeepers, and residents who eventually take up occupancy along the waterfront are going to enjoy not just river views, but a great location generally. The site is halfway between the City Center development and, on the other side of the river, nearby Coca-Cola Park, stadium home to the AAA baseball team, the Iron Pigs, which Deb Fallows wrote about here. And it’s only several minutes by car to major roadways like Route 22 and Interstate 78 and to the airport. In short, it’s in a pretty sweet spot.

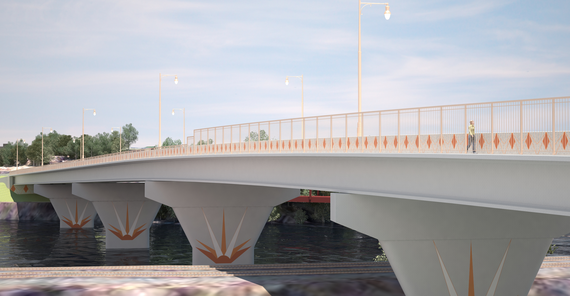

Success with projects of this sort comes from hard work and plenty of effective collaboration. Sometimes, serendipity lends a hand, too. The Waterfront development—and Allentown, generally—will get a providential boost from the completion next year of the new American Parkway Bridge immediately adjacent to the north edge of the Waterfront development’s footprint. The bridge, something people here have been talking about and wanting for over 35 years, will provide a new and fast connection between downtown Allentown and the east side of the river, with the highways (and airport) just beyond.

When we spoke with state Senator Pat Browne in August about the NIZ program that he maneuvered through the state legislature, he said of the Waterfront development, “The Waterfront is a bigger challenge than the City Center. But it has great upside potential.” There’s no gainsaying that.

The NIZ money that’s spurring this development will lower rents on Class-A office space and luxury apartments to affordable levels that will attract tenants. The site offers easy access to connecting highways and amenities like a baseball park and a hockey arena. The project will offer walking access to a revitalized riverfront and will spur the sprucing-up of adjacent areas.

All of this combined spells a development that makes progress toward the “life-work-play” goal of urbanists and seems likely to make a huge difference in a city that’s trying to make its way along the comeback trail.