I found Principal Brian Williams in the lunchroom of the Sustainability Academy, a pre-K – 5 magnet school in the Old North End of Burlington, Vermont. He was easy to spot, the biggest guy in the room, sitting on a very small chair, talking with an 8-year-old tousled-haired boy who was having trouble with his writing. It was noontime, and Principal Williams asked me if I would like some of today’s lunch: “Beef stew. I made it myself.”

I was about to chuckle a “Sure, sure” when I stopped and thought that actually, maybe he had made the stew himself. It seemed like such a place where the principal might also be the cook.

Just 5 years ago, the Sustainability Academy (SA) was known as the Lawrence Barnes Elementary School, one of two failing schools (the other was H.O. Wheeler) in the needy, sketchy part of Burlington, where about 95% of the kids were on free or reduced lunch (the nation’s most reliable proxy for poverty), test scores were very low and enrollment was declining. The school’s neighborhood is home to a mix of the down-and-out, the frontier-pushers, and is also the first stop for many of Burlington’s constant influx of refugees and immigrants.

The town and school district were fraught about what action to take for the failing schools. One side suggested the traditional approaches: redistrict or bus kids or shut ’em down. The other side said transform Barnes and Wheeler into magnet schools so good that parents from all over town will be knocking down the doors to send their kids there. They went with the latter, and Barnes and Wheeler became the first magnet schools in Vermont, with themes of sustainability (Barnes, which is also the first sustainability-themed public elementary school in the US) and integrated arts (Wheeler).

By last year, every measure was trending in a positive direction: test scores at SA were way up, as were attendance and morale. The percentage of kids on free or reduced lunch dropped into the 70s. There is a rich ethnic mix of students, including roughly 46% white, 22% black, and 26% Asian. Or as Principal Williams put it another way, 50% from families traditional to the neighborhood; 20% who believe in the mission of the school; 30% new arrivals to Burlington from around the world, and speaking 15 different languages. There was a waiting list for kindergarten enrollment. The report from the middle school where the kids go next — that you couldn’t tell SA kids apart anymore — was perhaps the biggest compliment of all. (Some of the statistics cited in this post are from here. )

So here I am eating beef stew, sitting on a tiny chair, talking with a little boy who said his problem was that he didn’t know what to write about. I told him that I just write down what people say, and that might be a good way for him to start, too. He took a blank page from my reporter’s notebook. What I was really looking for, beyond the starting point of all the official numbers and mission statements, was a window into the soul of his school.

Sustainability Academy is a lot of syllables for the name of an elementary school. But in Burlington, where if there were a word cloud of words spoken, “SUSTAINABLE” would be in the biggest font, no one bats an eye. I heard the word all over town— in the community agriculture and “localvore” movements, in the leading-edge walkable-only commercial zone, about the smart and user-friendly recreation developments, in the entrepreneurial ventures, City Hall, and on and on. At the school, “sustainability” is broadly, if vaguely defined as improving everyone’s quality of life, not only environmentally but also economically and socially.

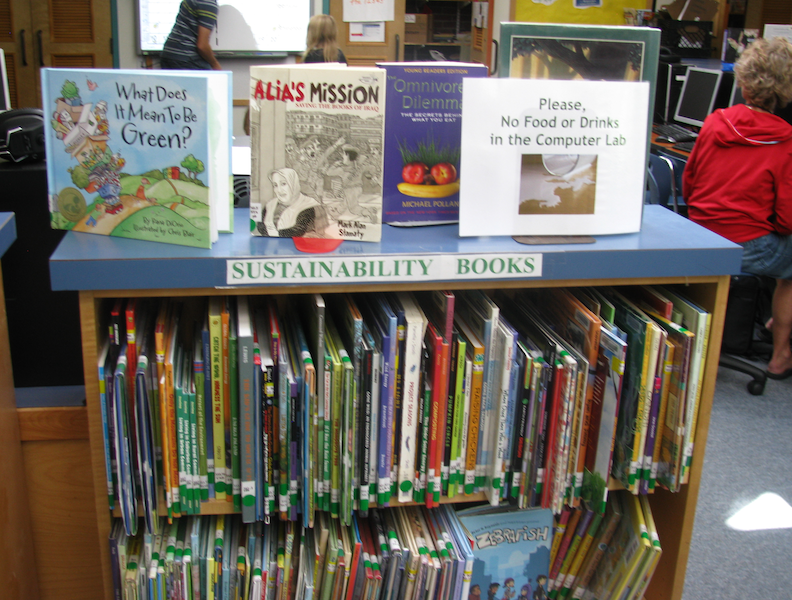

Practically and academically, this means using the school as a lab for lessons in pursuit of these lofty goals. The environment part seemed easiest. The older kids can learn about energy and electricity by examining ways to heat and cool their own school. (now solar and geothermal) The younger kids can study cycles of nature firsthand via the garden’s compost and recycling systems.

What seemed harder to address are the other pillars of the definition: the quality of economic and social life. Where do you start when you’ve got a population of kids that includes the daughter of the principal and the son of parents who grew up in refugee camps? And a child whose life experience is so raw that he pees in the corner of the classroom because he can’t imagine a toilet in a restroom? How do you introduce the idea of a PTO to parents who have never been to school themselves? How do you begin to shape a culture in a neighborhood where there are drug busts on one side of the school and urban chic deli’s and Himalayan food markets on the other?

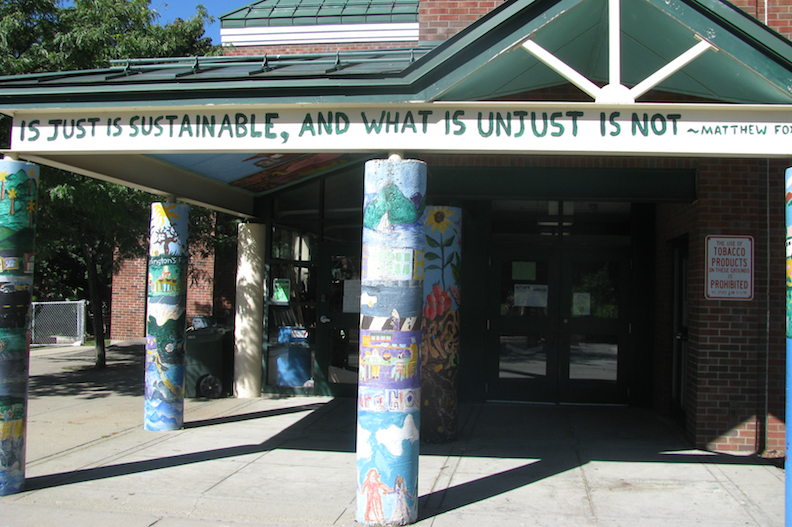

If SA has the answer, it is that you do everything, and you do it as well as you can. You draw on the special community that is Burlington, including hands-on buy in from nearby Shelburne Farms to work with the school; Seventh Generation, a Burlington company that makes eco-friendly cleaning products, to provide funding and time; parents and local talent who will help construct anything you want to build or paint; the police to forewarn you when a drug raid is about to happen. You don’t put a fence around the school to keep out the elderly neighbor who you discover takes a few vegetables from the school garden early in the mornings. You try to explain it to the kids when the rock garden they all worked to build was vandalized the first (and only!) time, and you encourage them to rebuild.

You have big dreams for the future — a new playground, treehouses. And you make immediate wins for the present — everyone will learn to ride a bike (get bikes and a place to store them!) and how to swim (use the nearby beach!). You make a compost heap, build raised gardens, an open-air classroom, and paint the school with murals. You procure a few very useful things, like a washing machine.

You go to the local universities and ask them to send you “only the best” of their talent to help you out. And you become so good that you eventually get critical mass of teachers, parents, and invested community neighbors, friends, and advocates who just do it themselves if they see a need or if no one steps up. You might even make the beef stew. All these examples are true; together, I believe, they make up the soul of a school.

And to see the school in its own voices and words, check out this You Tube video from the Sustainability Academy home page.