Last week I mentioned that a civic-bankruptcy drama was about to reach a climax in the beleaguered city of San Bernardino, California. At 4 p.m. today Pacific time, 7 p.m. in the East, the city council will vote on a formal “Plan of Adjustment” to present to the federal judge overseeing its bankruptcy.

Here’s a little salt-in-the-wound aspect that San Bernardino officials will not have missed. Their city was once the center for state and federal legal activities in this “Inland Empire” region of southern California. But over the past generation, many of those courts and associated legal businesses moved away from San Bernardino to the neighboring, once-rival, now much more economically successful city of Riverside. So sometime before their legal deadline of May 30, San Bernardino’s team must drive the dozen miles down the freeway to the big, bustling judicial center in Riverside, in its nicely restored downtown, to let United States Bankruptcy Judge Meredith Jury begin considering their plans for digging their own city out.

1. The Details

Late last week the details of the recovery plan were made public. The city manager and the city attorney formally presented them to the council, drawing on years of work by the Cincinnati-based consulting firm Management Partners. The plan is now online as a Scribd document. Here it is, in its 79-page fullness:

San Bernardino recovery plan for Plan of Adjustment

The document paints the economic backdrop—”By almost any measure, the Great Recession continues to have a devastating effect on San Bernardino’s residents and their economic resources”; it explains the oddities of the city’s governing structure; and, and it goes on to propose adjustments.

If you’d like to see some of the reasoning leading to today’s diagnosis and prescription, you could check out this Management Partners presentation to the city from January, 2014. If you’d like to see the “Vision Statement” that city officials prepared as they were nearing bankruptcy, you can find it here. (“In 2025, San Bernardino will be a prosperous community that … will serve as a destination for youth sports and recreation, cultural heritage and as a hub of governmental activity and professional services.”) And if you’d like ongoing coverage of who is getting what out of the bankruptcy plan, please follow stories by Ryan Hagen in the San Bernardino Sun. For instance, this over the weekend about community support for the plan, and this about the plan’s fine print. (The Sun has a metered paywall after a certain number of stories; you can get an online subscription, as I have done.)

2. The Big Structural Issue

I’ve mentioned before that San Bernardino’s immediate problem is that its people are so poor—and that its main employers have left town or shut down, and its unemployment rate is high. But the deeper problem is the structure of the city’s government, which has made it difficult-nearing-impossible for San Bernardino to apply its resources where they are needed most.

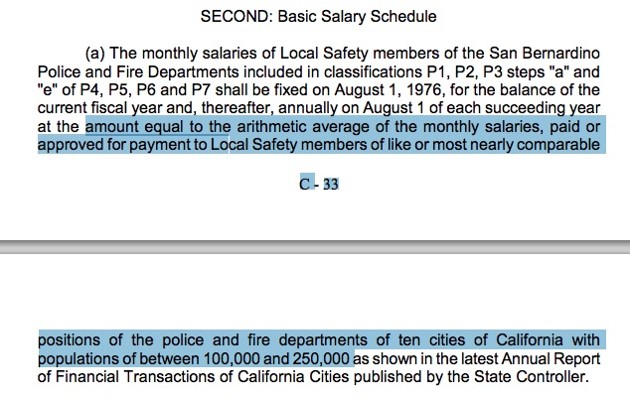

The most famous example, worth absorbing in detail, is the bizarre “Section 186” system of determining pay for the city’s police and fire services.

Most cities take it for granted that pay levels will be set through some process of collective bargaining, political decisions (e.g., city council votes), yearly proposals by a city manager or budget official, a mayor’s annual budget statement, or some other means of having politically accountable officials respond to changing economic realities. San Bernardino’s approach is different, and as best I have been able to determine is literally unique.

No elected or appointed official in San Bernardino has any direct control over pay for public-safety workers, namely police and fire-fighters. Expenses in this category make up 72 percent of the city’s entire spending; and they have been going up as the city budget prospects have been getting worse. But under the city’s operating rules, its officials are flatly forbidden to adjust, renegotiate, or trim the pay levels, even as they scramble to cut costs elsewhere.

Why is this a problem? In the CEO world, comparable-index pay schemes often turn into a ratchet, perpetually moving salaries up. The “compensation” package (I always put the term in quotes, because it’s such a euphemism) for the CEO of company #1 is tied to the average for CEOs and companies #2 — #10. The comparable index always seems to move things up rather than down, so the raise for CEO #1 soon ripples through to everyone else — and then back to #1 again.

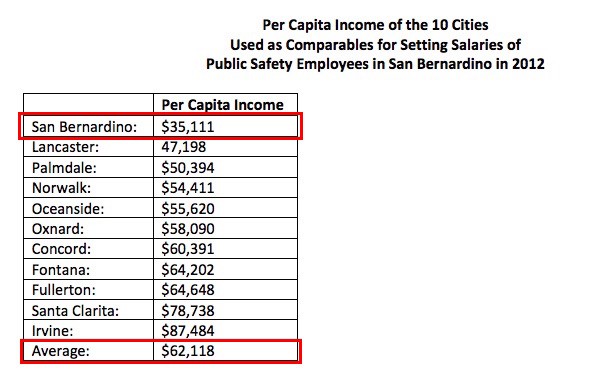

The San Bernardino-style index is worse than that, because the “comparable” cities are so very non-comparable. Since San Bernardino is the poorest city of 50,000 people or above in California, by definition any group of ten other cities will be richer. Thus this perverse result: whenever Irvine, Oceanside, or some other prosperous coastal-California city decides it can give raises to its police and firefighters (from its soaring property-tax assessments or startup-firm revenue), San Bernardino is obliged to give matching raises (from resources it does not have). The City Council cannot vote otherwise; the Mayor and City Manager cannot negotiate a different deal.

A team of researchers from George Mason University illustrated the difference between San Bernardino’s resources and those of a recent group of “index” cities. The set of ten changes, but all of them are always ahead of San Bernardino.

The George Mason report went on to say:

The figures above hint at the city’s financial struggles. A third of the city’s residents fall below the national poverty line, making San Bernardino the poorest city of its size in the state. To exacerbate matters, as John Husing pointed out in his presentation in March 2013 at the University of California Riverside, the median household income of the cities used to establish public safety salaries in the city were between 34 percent and 149 percent greater than that of San Bernardino.

The practical consequence of Section 186 is that San Bernardino’s reference to population, rather than average income, places a disproportionate burden on already strained local finances. As an unfortunate consequence of politics and historical trends, the city found itself committed to salaries and pensions that were neither proportionate nor sustainable.

How important could this be, really? More than you would think. As the George Mason team pointed out, if San Bernardino zeroed out its spending for every function except police-and-fire, it would still have a deficit. And in one more perverse twist of cycle, a city with per capita income of $35,000 ends up paying its public safety workers total compensation of about $160,000 apiece, or about $40,000 more than the statewide average. Why? Since the city government can’t control salaries, it eliminates positions; and then the remaining police and fire fighters do a lot of very expensive overtime work.

3. Why You Should Care About This, If You Don’t Live There

If you’re from San Bernardino, the process leading up to the City Council’s vote today, and leading out from whatever Judge Meredith Jury decides, is of obvious importance. Rebuilding the town’s economy, improving its schools, re-knitting its long-frayed civic fabric are going to be long, slow efforts in the best of circumstances, even when the city sheds the enormous millstone of official bankruptcy.

But some people in San Bernardino have decided that they’re tired of the failures and are ready to make things work. We wrote about the young members of Generation Now, in an earlier dispatch. After this long immersion in past troubles, the upcoming dispatches will be about people in its schools, in its business community, in its arts world who are excited about what comes next.

But while we’re still talking about what’s broken, and let’s spell out the connections to broader national themes.

— The bad economy post-2008 hurt everyone. But this sizable, vulnerable California city was hurt much more badly than most, mainly because of boring-seeming operational flaws in rules-of-governance.

Moral: things don’t have to be interesting to be important. I find “civics” and “governance” almost too tedious to type, but this is an example of how they matter. In most of the cities we’ve visited, civics and governance are surprisingly healthy. In San Bernardino they’ve been unhealthy for a long time—in ways that command attention as we reflect on the chronic diseases of national-level governance.

— A disengaged general public will lose to a committed special interest every single time. In his famed works The Logic of Collective Action and The Rise and Decline of Nations, the late economist (and my friend) Mancur Olson explained that liberal democratic systems naturally tend toward special-interest dominance.

Here’s how that looked in San Bernardino: Last year, an alliance of city officials, business people, and reformers tried to change the auto-pilot pay provisions of Section 186 in the only way possible, though a public vote to overturn that part of the city charter. Their effort was called Measure Q, and as this story in the Sun recounts, it lost by a small margin in a very low-turnout election. Very few of the city’s police and fire employees actually live in San Bernardino, so they couldn’t vote. But their organization outspent the other side by about eight to one to defeat the measure.

— I said that a 1981 study of San Bernardino was “heartbreaking.” That is because even when the city was enjoying what seems, in retrospect, an economic Golden Age, the civic culture was suspicious and non-cooperative. “There is an almost tangible absence of concensus [sic] among the residents of San Bernardino about the sense of identity and unity of purpose—the spirit of the community-at-large,” the team from the American Institute of Architects said. “Furthermore, [there is] a surprising apathy toward efforts to address this issue.” Since they were architects they noted:

A fuzziness which characterizes the boundaries of the city limits and makes them impossible to distinguish from unincorporated areas sometimes right in the city’s midst. The central business district has a heart but no body, and even individual blocks have lost the delineation of the grid pattern because of vast open spaces of vacant land or parking lots.

Moral: Rules of operations matter. But norms—the understanding of what you “should” do even if you you’re not legally obliged to do so, a sense of others’ and of the long-term good—matter too, and sometimes matter more.

About an hour from now the San Bernardino City Council will vote on changing the rules of the city’s operation. We’ll be telling you more about people trying to change the norms. Good luck to them all.