After a week-long trip through Ohio in late August, I posted this account on my Substack site. It is all the more relevant here, because it concerns the central theme of Our Towns: why it matters that Americans know more about the full American story of this era.

It’s part of a paired set of overview posts about Our Towns travels in summertime 2022 America. Next up in this space will be a new overview by our colleague Ben Speggen, introducing what he and our colleague (and his fiancée) Michelle Ellia found in their recent days on the road in South Carolina (which you can now find here). Then in coming days, all four of us will weigh in with more detailed reports on people we have met and the communities we have learned about. Most of these places are in the middle of transformation and renewal via the Community Heart & Soul® process, which we’ve learned and written about over the months, and which is a partner and supporter in our reporting.

Now, my overview:

This post is about the challenge of knowing one’s own country—a challenge that is almost an impossibility for a country as large, diverse, contradictory, and rapidly changing as the United States. The same of course applies in China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, “the Arab world,” and other places.

But what Americans “know” about this moment for their country seems skewed in ways that are dangerous and destructive—yet potentially correctable. I hope you will bear this dispatch in mind the next time you hear a report on “a nation on the cusp of civil war,” or “Red and Blue America, with no common ground in between.”

I’ll start by declaring my premises on three points. Then I’ll give a list of illustrations from the past seven days that my wife, Deb, and I recently spent in parts of America not usually covered in the news.

Three principles:

Here are three points that guide what I write about America and the world.

1. Keeping contradictory truths in mind.

Through the years Deb and I were living in China, it would drive me crazy when experts would opine from afar on what was good or bad about the place. The certainty of their views and the sweep of their theories seemed directly connected to how little they’d seen of the country, except at some internationalized conference center in Beijing or Shanghai or Sanya.

By contrast, most reporters on-scene tried constantly to portray how China was both better and worse than it seemed from afar. Both stronger and weaker, both more likable and more offputting, both more tender and more cruel. And that the main challenge in dealing with it was trying to keep these contradictions in mind. This is one of many reasons it’s bad for the world that Xi Jinping’s government is making it so hard for foreign reporters and foreigners in general to be inside China.

This principle of contradictory realities does not apply just to China.

2. The arc of loss and rebirth—and how a culture stays ‘young’

Through the years I have lived in and studied American history, I’ve come to believe that the through-line in the nation’s story is constant loss, and constant creation.

The loss and change are certain: Name your decade since the 1620s, and I can name the emergency or tragedy of its times. Name your American family, and its background will include hardship and dislocation. Name your community, and it will have gone through significant ups and downs. For instance: Bend, Oregon, now one of the country’s most desirable locations, had some of the worst unemployment in the country 30-plus years ago, when the logging and timber industries collapsed. At about the same time, the now-celebrated Greenville, South Carolina, had a textile-based economy. Nearly all of those mills have disappeared, but Greenville has adjusted and prospered.

For arc-of-history purposes, the question is always how the creation in any given era balances against the destruction. Who is helped and hurt; how the gains offset the losses; who is able to recover; how to protect those who cannot. Change is a given; adjustment to change is the variable, and the one more within our control.

The older people become, the more likely they are to mourn how things “used to be.” The younger they are, by the calendar or in spirit, the more likely they are to think about what comes next.

When people say that America is a “young” country, this is what they mean. Despite having the oldest continuous form of government of any major country, and apart from immigration giving the U.S. a lower median age, what makes America young is an orientation ahead, rather than behind.

3. ‘The rest of the country is in trouble. In my town we are working things out.’

Through the decade in which Deb and I have reported on the goods and bads of smaller-town American life, we’ve become convinced that national media’s focus on “heartland” America mainly as an arena for Red-vs-Blue political showdowns (“guy in a diner”) has a profoundly distorting effect. As someone wrote about this problem:

An important part of the face of modern America has slipped from people’s view, in a way that makes a big and destructive difference in the country’s public and economic life. Despite the economic crises of the preceding decade and the social tensions of which every American is aware, most parts of the United States that we visited have been doing better, in most ways, than most Americans realize.

Because many people don’t know that, they’re inclined to view any local problems as symptoms of wider disasters, and to dismiss local successes as fortunate anomalies. They feel even angrier about the country’s challenges than they should, and even more fatalistic about the prospects of dealing with them.

As you’ve guessed, that someone is me, in the introduction to the book Our Towns. I wrote that four years ago; I am here to tell you that Deb and I believe this all the more strongly now than before the pandemic.

Because virtually the only thing Americans know about the parts of the country where they don’t live is the non-stop crisis narrative of national media, they naturally think the country’s problems are even worse than they are. In the parts of life they experience directly, people can see the goods and bads in perspective, and recognize not just possibilities for progress but encouraging practical steps. It’s hard to realize that all across the country, people who are never in the news are innovating and progressing in similar ways.

Now let’s make this specific.

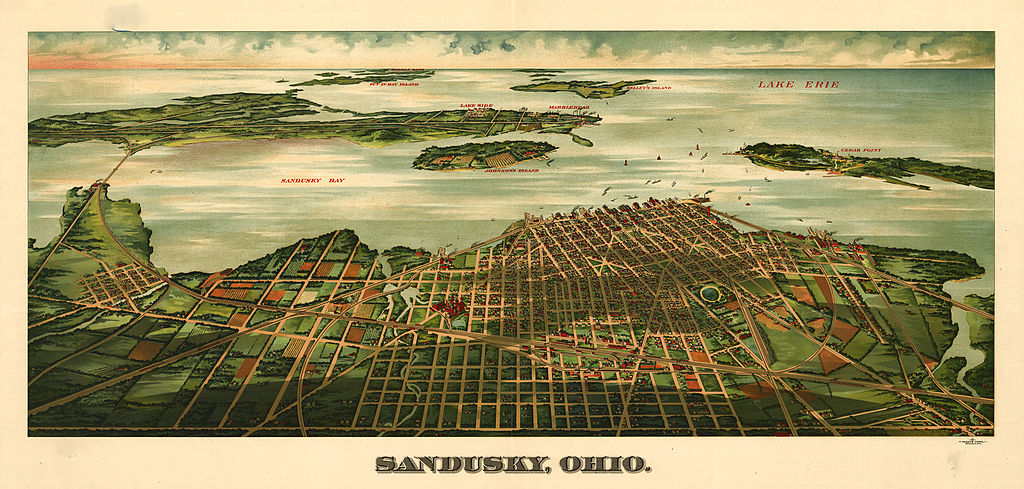

Over a seven-day period this month, Deb and I interviewed and met people in six smallish, and very small, towns and villages in northwest Ohio. This is where Deb grew up, on the shores of Lake Erie, and where she considers herself “from.”

It’s also an area that, if it ever appears in the national news, is usually in the context of “despair and division in the heartland,” the latest Biden approval ratings, what the Vance-Ryan Senate race means for next year’s legislative agenda, and why Arizona and Nevada have become “swing states” but Ohio no longer is.

All those things matter.

But here are some of the other things that matter but are rarely if ever in the national news, and therefore are not part of general understanding of “how America is doing.” Each of these is a place marker for upcoming more detailed reports by Deb and me at the Our Towns site.

—The Community Foundation. Findlay, Ohio, is the county seat of Hancock county, with a city population of more than 40,000. It’s the regional hub. Over the past three decades, the Findlay-Hancock County Community Foundation, headquartered there, has become a force in regional well-being whose effects can be compared to those of the great Gilded Age philanthropies in Pittsburgh. (Mellon, Frick, Carnegie, Heinz, etc.) Everywhere we went in the area we saw the Community Foundation’s imprint. What it has done deserves study and emulation.

As far as we can tell, this Community Foundation, which is transforming a region, has not been mentioned in mainstream national news.

—Family Center. One of the Community Foundation’s projects in Findlay is the “Family Center,” in a former large grocery-store building on the north side of town. The insight behind this Center was the importance of combining a range of nonprofit services—medical and dental clinics, housing and homelessness assistance, legal aid, a library, a food pantry and thrift shop, and more—all in one place. That way, as we heard, families for whom a $20 taxi ride was a decisive barrier could do all their business in one attractive and dignified place.

We have not seen anything like this in other cities. It’s a story worth learning from. Again, as far as we can tell, it has not been featured in the national news.

—Sandusky on all cylinders. Sandusky is the county seat of Erie County, on the lake, and has a population of just over 25,000.

More is going on there, in more different areas and directions, than I can even suggest at the moment. I’ll give just two illustrations.

First, we happened to be there at a moment when the national spotlight hit Sandusky. At an event on the waterfront, a trans-partisan group got together to announce good news on the “infrastructure unites us all” front. Rob Portman, the outgoing Republican Senator from Ohio; Marcy Kaptur, the very Democratic Representative from the district; and Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend and now Secretary of Transportation, were on hand to celebrate Sandusky’s success in winning a competitive $25 million grant for local road, transit, and bike improvements.

Second, one of the most impressive breweries-and-pubs you will find anyplace in America is in downtown Sandusky, founded by Kha Bui (above), who was born in Saigon, then left as a child on a boat into the South China Sea and spent several years in refugee camps. The brewery is called CLAG, and the adjoining restaurant/pub is called Small Cities. Each time we went near the place, it was packed. Kha Bui’s idea is to sell certain lines of his beer only at the taphouse and restaurant, so that people will have to come to Sandusky to get it. Again as far as we can tell, they have not been in the national news.

—Sandusky, in perspective. When reporting from “they’ve already succeeded” towns, like Greenville or Bend or Burlington, Vermont, Deb and I often wondered what it would have been like to be there ten years earlier.

I think it would be like being in Sandusky now.

And this is not even to talk about the school system or the faith community. Or a new branch of Bowling Green State University. Or other aspects we will return to.

—Villages, challenging what you think about small-town Ohio. One of the Community Foundation’s many projects in Hancock County has been supporting smaller villages’ enrollment in the Community Heart & Soul® process. (Heart & Soul has been a partner and supporter of Our Towns reporting.) The three villages we visited—village is the technical term— that had been through this process were really small. Mount Blanchard’s population is around 500. Arlington’s, about 1,500. And McComb’s, about 1,600 — though it also is home to the largest cookie-and-cracker factory in the country. That will be a story of its own.

Yet each of these communities, surrounded by corn and soybean farms, and with a population base smaller than an average city block in New York or Chicago, has engaged in a systematic civic-engagement process to help it identify what its residents most care about, and where it should invest its efforts.

Mount Blanchard discovered and rehabilitated old ball-playing fields that had been left neglected. It has better park facilities than most places with 20 times its population. Arlington has attracted young people back to town, and has ambitious retail and restaurant investments. (For instance, Hurdwell.) And in McComb, we met fully 1% of the town’s total population — the equivalent of 7,000 people in our current home town of Washington DC — at a meeting to discuss already-approved plans to build more housing, and in-progress plans for a revived downtown. More on all of these to come. But in all of these tiny communities, we saw counter-examples to the idea that Americans no longer engage with their neighbors.

—Vermilion, which is Deb’s homeland, has deliberately made the most of its assets, which are a lakeside setting and still-extant traditional architecture. Its streets, shops, and restaurants were jammed when we visited two days ago.

We didn’t ask any of these people in any of these places for their views of national politics. But in all of them, from the larger cities to the smallest settlements, people younger and older, Black and white, volunteered their optimism about prospects for their communities. In one of them, a civic leader took us through all the “used to be” sites — the gas station, the grocery store, the hardware store. “They’re all gone,” he said. “But I know that towns like this are coming back.”

Is this the full American story of these days? Of course not, and no one knows where these village-by-village ambitions will lead.

But it is part of the story, And part that is too often left out.