Everyone knows that local newspapers are in trouble. That’s why Deb Fallows and I have been chronicling examples of smaller papers that have bucked the economic trend—in Mississippi, in coastal Maine, in rural communities across the country.

But what “everyone knows” about the main source of the problem may be wrong—or misleading enough to divert attention away from a possible solution.

The conventional view of the local-journalism crisis is that running a small-town newspaper just isn’t a viable business anymore—now that internet advertising has drained off revenue, and now that virtual communities and social media have displaced real-world connections and communities.

Those pressures are all too real. (Sobering details on the collapse of ad revenue are here.) But some of the remaining success stories in this troubled field suggest that the ownership structure of local news organizations may matter as much as internet-era advertising shifts, in determining which organizations survive and which perish.

In short: Increasing evidence suggests that the local newspaper business may still be viable, simply as a business. What it can no longer do is provide the super-profit levels that private equity groups expect from their holdings, and that they demand as a condition of even letting the papers exist. But the same papers that are doomed under private-equity ownership might have a chance in some different economic structure.

This proposition—that newspaper ownership is as important as internet-era advertising trends, in deciding local journalism’s future—was examined at length in a 2017 article in The American Prospect by Robert Kuttner and Hildy Zenger (the latter a pen name). It has been a theme connecting our previous newspaper-survivor reports, from Maine to Mississippi. And it is the idea behind a new weekly print newspaper whose first edition came off the presses this month, in Provincetown, Massachusetts, at the tip of Cape Cod.

The long-established paper for “Outer Cape Cod,” the communities from Provincetown southward, was the Provincetown Advocate, founded in 1869. In 2000, it was bought by the Provincetown Banner, and in 2008, the Banner was sold to GateHouse Media Inc., a private-equity-run chain of mainly smaller papers across the country. Long-established newspaper chains like Gannett, Knight Ridder, and McClatchy have their problems and detractors. But their goal, as Kuttner and Zenger pointed out in their Prospect piece, was fundamentally to operate newspapers. Their operations paid at least lip service to the idea that newspapers had a civic and community role, beyond their sheer economic existence.

The modern trend in small-paper ownership is their takeover by private-equity firms, of which Alden Global Capital, its subsidiary MediaNews Group (formerly known as Digital First Media), and GateHouse are the best-known examples. For these institutions, newspapers are a financial asset like any other—like a tract of commercial real estate, like a steel mill or a suburban mall. The profit-maximizing model they have applied to countless small papers has been: slashing costs, mainly by laying off reporters and editors, so as to boost short-term profit rates; continuing the cutbacks, so as to maintain profit margins, even as a thinner paper attracted fewer readers and ads; and when there was nothing left to cut, declaring bankruptcy or closing the paper, which had in strictly financial terms reached the end of its useful life.

The Banner, in its GateHouse years, has gone through a version of this cycle. (For the record: I have called and sent messages to relevant GateHouse officials, and will report back if I hear from them.) At the time of its sale, it had a staff of about 20. By early this year, the staff was down to four.

“When people think about corporate ownership of newspapers, they think the problem is that the company is telling you what to write—like Sinclair, with its broadcast stations,” says Ed Miller, a longtime newspaper entrepreneur who worked as an editor at the Banner starting in 2015.

“The fact is, they couldn’t care less what you write,” he says. “Their only interest is how much profit you can squeeze out of the operation, so the way they actually undermine the reporting of news is simply by laying off staff. The cuts make the job so overwhelmingly difficult to do that there’s just no possibility that you will get into serious news coverage, or investigating the stories that need to be dug out.”

In July of this year, Miller resigned from the Banner. This month he and his wife, Teresa Parker, published the first print edition of a new weekly print newspaper, The Provincetown Independent, aimed at readers, advertisers, and citizens in the towns of outer Cape Cod. This month’s paper was a preview, and regular weekly print publication will begin in early October. In the meantime, new stories are being posted online.

The territory the Independent is covering is more diverse than the vacation-time imagery of Cape Cod might suggest. The communities in its market—Provincetown, Truro, Wellfleet, and Eastham—have median incomes at about the national-average level (or in the case of Provincetown, significantly below it). Some of the residents have vacation homes there; some are service workers, small merchants, and businesspeople, or part of the working fisheries. Provincetown has long been an LGBTQ haven; the outer Cape has well-established arts, scientific, marine-science, and tourism-oriented institutions.

“This is an interesting community,” Miller told me. “There are a lot of engaged people here, there is money here, this is a place that ought to be able to support a perfectly successful, profitable newspaper.” As they observed the shrinkage at the Banner, which recently laid off its last local reporter, Miller and his colleagues began thinking about a new venture they might launch.

The approach they decided on—which you can read about on the Independent‘s own site, or by Allison Hagan in The Boston Globe and Sarah Mizes-Tan for the local public-radio station WCAI—was a mix of normal for-profit business structure and nonprofit adjunct.

The business plan is based on a four-year hoped-for course to profitability, at which point the paper would have total paid circulation of 6,000 per week, and 19 full-time staffers. So far Miller and Parker have raised a little more than half of the business capital they are looking for. The nonprofit operation has raised three times as much as its original target. This money will be used for special projects—training young journalists, supporting investigative efforts, long-term projects on “themes that are important to the community, like how young families will manage to live here,” Miller told me.

August Carnival parade in Provincetown (Courtesy of Marcia Geier)

August Carnival parade in Provincetown (Courtesy of Marcia Geier)For all the ceaseless technological and business change in the news business, Miller said, “the basics of the business are that people love local newspapers. If you can provide something they want, especially information they can’t get anyplace else, they will be loyal to you.”

The weekly publication schedule of the Independent, like the every-other-week schedule of The Quoddy Tides in Maine, helps the paper resist any temptation to cover breaking national or world news, for which readers have a million faster, better sources. Instead it can cover local developments—taxes, schools, zoning, real estate, religion, business ups and downs—that simply won’t be covered anywhere else.

“People are saying we need to come up with a new business model” for small newspapers, Miller told me. “Actually, the old business model for a local newspaper that really does its job can actually work pretty well.” He said that he canvassed owners of similar-scale papers around the country, and found that a normal profit rate was about 8 percent of revenue. For a private-equity fund, that’s nothing. “But if you’re running a normal local business, 8 percent is pretty good.” Miller said that one local-paper owner told him, “If I’m making more than 8 percent, I know it’s time to reinvest in the business—hire more people, give them raises, upgrade our equipment.”

Cape Cod in the summertime (Courtesy of Elspeth Hay)

Cape Cod in the summertime (Courtesy of Elspeth Hay)One of the Independent’s advisers and business backers is Louis Black, who in the 1980s in Austin co-founded and edited the successful and influential alt-weekly The Austin Chronicle and then was a co-founder of the mega-successful SXSW. I spoke with him by phone today to ask why he’d become involved.

“When we started the Chronicle, we didn’t know what we were doing,” he said. “It took a decade to get up to speed. Eventually we realized a paper like that creates the community. It pulls it together, then sends it out.” Black said that despite the travails of print media, this was the role that he hoped papers like the Independent could fulfill.

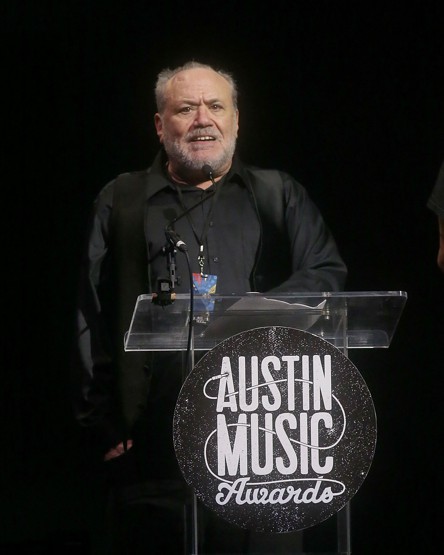

Louis Black speaks during the 36th Annual Austin Music Awards (Gary Miller / Getty)

Louis Black speaks during the 36th Annual Austin Music Awards (Gary Miller / Getty)“It’s not just about conveying information,” he said. “People have new ways to do that quickly. It’s about providing a cultural and intellectual center—and not only for like-minded people. It’s for people who want to engage in debate, and have principled debate. A strong local paper can do that. It’s not just about the words or information. It’s the spirit.”

Black met Ed Miller and Teresa Parker because Black had a neighboring house in Cape Cod. He learned that he and Miller were both from Teaneck, New Jersey, and both had spent their careers starting publications—Black’s with more financial success. Eventually Black decided to put time and money into the new Independent venture.

Did he think that it realistically had a chance? Black laughed, chuckled out some version of “Who knows?,” and then said: “Because Cape Cod is what it is, and because Ed is who he is, I think they have a shot.”

Like Miller, and like me, Black is from the dreaded and aging Baby Boom generation. “We’re too old to do this,” Black told Miller, as they considered the years-long, dicey effort of starting a new publication. “But the young people don’t know how, and we have to show them. People need to see that it can be done.”

“I want to hang the sword up,” Louis Black told me. “But we can’t. We’re living in a world where if we believe, we have to engage. And it matters.”