After our first pass through Dodge City two weeks ago, I reported that the mood there, in a part of the United States that is very heavily affected by Latino immigration, was at strong variance with the “build a wall” / “take our country back” tone of Donald Trump’s campaign.

The contrast with Trump’s rhetoric was significant since this is a politically conservative area in a politically conservative state, which Trump is almost certain to carry this fall. Over the past 30-plus years, the ethnic makeup of southwestern Kansas has shifted from majority white to majority Latino—and the Latino group mainly means Mexicans. This is especially so in the “triangle” of Kansas cities that dominate the meat-packing and feedlot industry: Dodge City and Garden City (which we visited), and Liberal (which we did not).

“Packing house” is a nicer term for what once was called a slaughterhouse, much as “meat solutions” is a nicer name for the company, and “harvesting cattle” is a nicer job-description term for the work of putting animals to death, one after another, through the work day. We didn’t push for a look inside the packing houses during our visits, because I have seen places like them before and understand their reality. (The second article I ever did for The Atlantic, when I was free-lancing from Texas in the mid-1970s, was about what it was like inside the Iowa Beef facility in Amarillo, then America’s largest beef slaughterhouse. The premise of the story was that if you eat meat, as I did and do, you should confront the process by which that meat reaches your table.)

If you do eat meat, you are part of the economy that supports the packing houses; the associated feedlots that ring the city and in which the animals spend the final months or weeks of their lives putting on weight; the trucks that roll in non-stop, bearing live animals into the huge buildings on the south side of Dodge City and carrying boxes of cut meat back out; and also the many thousands of people who earn their living inside. Something like a quarter of the beef eaten anywhere in the United States comes through the feedlots, packing houses, and shipment centers of this corner of Kansas. Large quantities are also shipped overseas. This is work America (and the world) wants done, and the people in Dodge and Garden Cities are doing it.

The employees in these factories are nearly all immigrants. In the 1980s, a substantial number were recent arrivals from Vietnam. Now they’re mainly Mexicans and others from Central and South America; plus an increasing number of Somalis and other Africans; plus some Southeast Asians and others. Pay rates vary but are much above minimum wage. For instance, a current listing for a starting position in “beef harvesting” at Cargill offers $15.50 an hour, with medical and 401(k) benefits, in an area where living costs are very low. The work can obviously be unpleasant and extremely hard.

“I can tell you that no matter what wages you paid, you are not going to find any reasonable number of ‘native-born’ Americans who will do those jobs,” a man who has been a manager for a large packing house in the area, and preferred not to be identified, told us. “Your Anglo community is not going to work there, pretty much regardless of the wage. The entire meat-packing industry depends on immigrant labor, and always has.”

The syllogism we heard from him and many others was: Without the meat-packing industries, these towns in western Kansas would have withered like others in the Plains. Without immigrants, mainly from Mexico, the meatpacking and feedlot industry would not exist. Thus the economic and cultural survival of places like Dodge City and Garden City depends on immigrants, some of whom arrive legally and many of whom don’t. “There are some pockets of people here who are ‘old school,'” the one-time packing house manager told us. “They’d like to ‘take America back’ and so on. But by and large, people here—Anglo and Hispanic and otherwise—recognize that we’re in this together. The immigrants are the engine that keeps this community alive.”

If you’d like to consult some academic studies on the importance of the meat industry and immigrant labor to the survival of these communities, you can read a new two-part report from Brian Hanson of the Center for Rural Affairs: part 1 is here and part 2 is here. A related Pew study is here. (Also: check out studies from the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association; the University of Missouri — Kansas City; the University of Kansas; and the University of Missouri-Columbia.)

“Latinos and immigrants are not only bringing population growth to rural America, they are also bringing economic growth,” Brian Hanson writes in his study. “Economists have found that, nationwide, rural counties with larger proportions of Latino populations tend to be better off economically than those with smaller Latino populations. Rural counties with higher proportions of Latinos tend to have lower unemployment rates and higher average per capita incomes.”

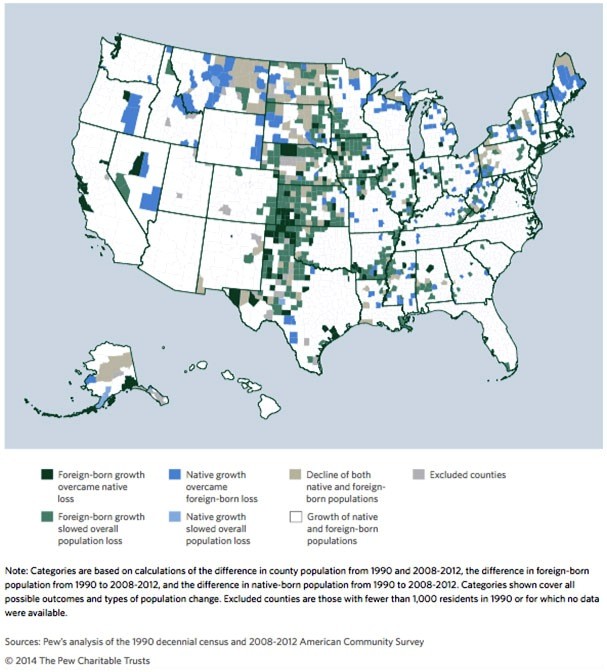

You might argue about the direction of the causal arrows: Are immigrants drawn to areas that already have strong economies? Or do they make economies stronger by their presence? Probably some of both is true. But the result is unmistakable. Across much of the plains and rural midwestern region of the United States, what has kept communities alive is new arrivals, mainly from countries to the south. The graphic below, from Pew, looks complex but is very informative. Its message is: rural areas that have attracted immigrants have continued to grow, and most others have plateaued or shrunk.

Much of what we saw in several visits to Dodge City and Garden City involves the human and cultural consequences of this migration, on the people who have recently arrived in southwest Kansas and those whose families arrived earlier. Deb and I plan to tell some of their stories in the next few days, starting here with that of Ernestor De La Rosa, who is now the assistant finance director and assistant to the city manager of Dodge City, and a sparkplug of civic life there.

If you listened carefully to De La Rosa for a minute or two, you could pick up clues that English was not his first language. But you would have to be listening closely. When Ernestor De La Rosa arrived in the United States at age 13, he did not speak or read English at all. He was born and raised in Mexico and first came to the U.S. on a visitor visa. Other members of his family were already in Kansas working in the meat-packing plants. He eventually joined them in Dodge City; finished high school and then college; got a master’s degree in public administration at Wichita State University, the leading school in this part of the state; and came back to Dodge City

Since 2000 De La Rosa and other members of his family have been in the queue to get a green card. He is able to work in the U.S. now because of “DACA,” or Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals, the Obama administration’s 2012 executive order that allows people who arrived before age 16 (as De La Rosa did) to get renewable work permits, and be exempt from deportation, while the U.S. figures out some longer-term reform to its immigration policy. (This is different from an extension of DACA that was the subject of the recent 4-4 Supreme Court standoff.)

“When I arrived, I was still a kid and didn’t think about what was happening,” De La Rosa told us. “I didn’t think: I’m going to a different country, I need to learn a different language. I didn’t think about any of that. More than anything, I was enthusiastic about my family and the schools, and the help I got there. I couldn’t be here now”—as a city official, a prominent young member of the city’s new ethnic majority—”without the help and encouragement of my teachers after I arrived.”

“We already have many leaders working in many sectors,” he said. “But I am hopeful that there will be more and more. If people see me working for the city, it might encourage others to step up. They might think, I could do that too. We’d like to encourage young families to participate more in city and county affairs, and be more represented in all local events.”

On other topics:

— How does it sound, from the Dodge City perspective, when national politics is dominated by talk of “building the wall”?

When we hear things like this, it just sounds so irrelevant. It’s not the story we are seeing here in Dodge City at all.

Our people here work. They want to establish themselves here in Dodge City. They want to raise their families and have a future. It’s unfamiliar to us, these comments being made on the national level. We are doing everything we can to integrate the newcomers and their families.

My reaction [to the general election-year controversy over immigration] is, You really need to be familiar with the Latino community, and even more with our broken immigration system. Why do we have this problem now, and what can we do to address it?

— Has the tone of election rhetoric made any difference in daily life in a town like Dodge?

I don’t have that perception. But I do think that individual Latinos, those of second-generation who are able to vote, they are registering to vote in this year’s election. Our community is registering, and we are going to participate actively in the upcoming elections.

— What’s the typical immigrant story in the area?

It’s a diverse population. But a typical story might be of people who came here undocumented. Then they got in the line for the process to adjust their status. You might have an individual who came here, worked, found a significant other, had kids—and through that significant other, or kids, was able to adjust their status.

I recognize that for Donald Trump, the right response to stories like this would be, Crack down much harder. For most of the people we met in western Kansas, of whatever race, the logical next step is to align the provisions of immigration law more closely to the economic and cultural realities of the area, which include a large, economically and culturally important foreign presence.

Recently, a lot of our young people have been able to get a better life with the new DACA. They are able to go to college, and after college seek employment, either to help our community or go someplace else to expand their career.

And this is what has affected me. After my visa expired I was in a kind of limbo, but under the DACA policy I am able to work for the city legally and help my community at the same time.

I asked De La Rosa about his long-term ambitions. He said that eventually he hoped to become a city manager, in Kansas or elsewhere. “I’d like to continue to help my community and encourage our Latino and other immigrants that you can do these things, even if you don’t start with the proper documentation. I’d like to encourage them to pursue their dreams.”

Again, I recognize that different people will read stories like Ernestor De La Rosa’s in different ways. For now I’m simply presenting his story, as one of a number we’ll be offering about the lived-reality of America’s changing immigration situation in an election year that features talk about “taking our country back.”

Plus one final note from the Anglo former meat-packing employee: “The reality here in southwest Kansas is that we are heavily influenced by the Hispanic culture, and not just economically. They are part of the fabric of our community. If they decided to pack up and leave, Dodge City would be a ghost town. And we realize that the future success of the Hispanic community predicts the future success of our community as a whole.”