Factory towns face problems when the factories shut down. Everyone has heard versions of that story—involving steel and auto plants in the Midwest, sawmills in the Northwest, coal mines in Appalachia or copper mines in the Southwest, other facilities in other towns.

On a recent visit to Southside Virginia—the part of the state bordering North Carolina, and far from the tech-and-government-driven boom of the D.C. suburbs in northern Virginia and the military-based economy of Norfolk and the Tidewater—we were reminded of the problems cities had even when those factories were up and running. We also learned about the way they are trying to apply the mixed blessings of a lost manufacturing heritage as they figure out their next act.

Our visit was centered in the city of Danville, which Deb Fallows wrote about here. Danville is the major city within Pittsylvania County, which is geographically one of the largest in the state. The city’s population is about 40,000, split roughly 50-50 black and white. In its day, it was one of the richest places in the Piedmont area, and a major center of first the tobacco and then the textile industries. Danville was also, for a one-week period in April 1865, the final capital city of the Confederacy—with implications down to the present, as we’ll explore in upcoming dispatches.

Now textiles have disappeared almost entirely, and tobacco hangs on in much-reduced form. (These days, the main tobacco-business force is JTI, or Japan Tobacco International, which has bought brands like Natural American Spirit and Benson & Hedges, and has expanded its warehouse and processing facilities in Danville.) While Virginia’s population has boomed—roughly 4 million in the 1960 census, 6 million in 1990, 8 million in 2010, and rising—Danville’s is a little smaller now than it was in the 1960s. This part of southwestern Virginia and western North Carolina has endured the simultaneous collapse of the three industries that were the mainstays of its many small towns: tobacco, textiles, and furniture making. Danville’s comparative good fortune is that it didn’t have as many furniture factories to lose as some neighboring places did.

And yet: Danville is now benefiting from another aspect of its battered industrial heritage, which it is beginning to turn into an important city asset. How? Please read on.

Old warehouses, awaiting renovation, in downtown Danville, Virginia (James Fallows / The Atlantic)

Tobacco got going in this region because of a combination of soil and slavery. The soil in central-southern Virginia is part of a belt reaching through North Carolina and Kentucky that is exceptionally favorable for tobacco. (The same territory also favors hemp, which is becoming the basis of another new industry. Stay tuned for more on that, too.) Before the Civil War, it was the home of large tobacco plantations and correspondingly large slave populations.

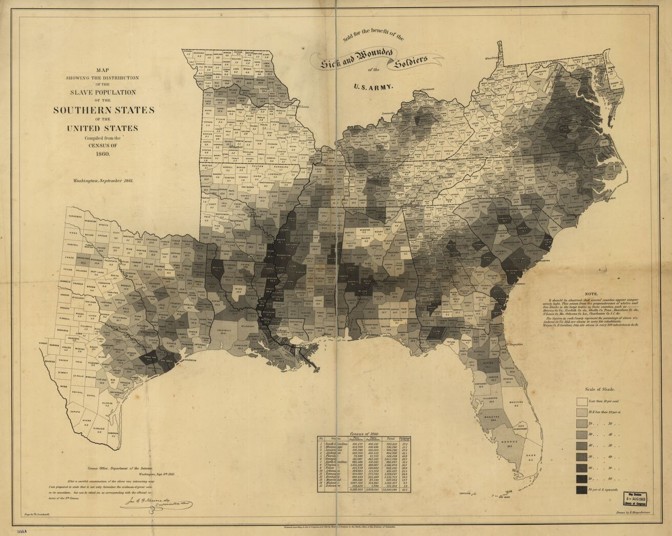

A fascinating map at Danville’s Museum of Fine Arts and History correlates Virginia’s county-by-county black population in the early 1860s with levels of support by the white population for joining the Confederacy. (It’s different from the map shown above but based on similar data.) The rugged Appalachian west of the state, including what later peeled off to become West Virginia, had very few plantations, low black populations, and also less support for secession. The tobacco heartland around Danville had more plantations, with more slaves, and (among the whites) stronger secessionist views.

After the Civil War, the tobacco industry remained, having shifted from a slave basis to sharecropping and low-wage labor. Auction houses, warehouses, and processing facilities for tobacco transformed the city’s downtown. Many of them were huge brick structures on the streets near the Dan River. An academic history of the area’s economic evolution, Danville, Virginia: And the Coming of the Modern South, by Michael Swanson, details the way that the tobacco industry shaped the physical and economic contours of the region through the 1800s—and how the textile industry, drawn down from New England by the search for lower wages (and hydropower along southern rivers), shaped them after that.

The Danville area, while retaining its tobacco business, also become one of the most important textile centers in the country. An operation eventually known as the Dan River Mills was by the mid-20th century one of the largest textile mills anywhere.

A central theme of Swanson’s book is how rough life within a mill town could be, for people other than owners and managers. Swanson refers to W. J. Cash’s famous coruscation of southern mill culture in his book The Mind of the South, published just before World War II. Part of Cash’s description is so floridly overdone that I won’t quote it in full. (It’s no surprise that as a young man Cash wrote for H. L. Mencken’s usually florid The American Mercury.) Here is a comparatively restrained sample:

The working conditions in the Southern cotton mills were extremely unfavorable. Men and women and children were cooped up for most of their waking lives in the gray light of glazed windows, and in rooms which were never effectively ventilated, since cotton yarns will break in the slightest draft—in rooms which, because of the use of artificial humidification, were hardly less than perpetual steam baths.

The harvest was soon at hand. By 1900 the cotton-mill worker was a pretty distinct physical type in the South; a type in some respects perhaps inferior to even that of the old poor white, which in general had been his to begin with. A dead-white skin, a sunken chest, and stooping shoulders were the earmarks of the breed …

The women were characteristically stringy-haired and limp of breast at twenty, and shrunken hags at thirty or forty. And the incidence of tuberculosis, of insanity and epilepsy, and, above all, of pellagra, the curious vitamin-deficiency disease which is nearly peculiar to the South, was increasing.

The mills’ influence was wide-ranging and profound. Businesses in the area discouraged higher education and brought in workers straight out of public schools. They effectively separated the region’s work force by race—mainly blacks as tobacco workers, whites in the mills—which reduced possibilities for labor cooperation, while reinforcing segregation. Nonetheless, greater Danville was the scene of repeated labor-related and racial strife for half a century after the Civil War, through the Reconstruction era and the beginning of labor organization.

Then, during the civil-rights era of the 1960s, it was again a battleground. Despite the Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 decreeing an end to “separate but equal” segregated schools, public education and most other aspects of Danville’s life were rigidly segregated into the 1960s. After civil-rights protests and brutal police response in the summer of 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. said that three places where he would focus his efforts would be Montgomery and Birmingham, in Alabama, and Danville.

The main civil-rights confrontation in Danville, on June 10, 1963, was known as “Bloody Monday,” when police used fire hoses and billy clubs against demonstrators. A local grand jury also indicted many of the demonstrators under a pre–Civil War–era law, passed in response to the John Brown abolitionist raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859, that made it a crime to incite “the colored population to acts of violence or war against the white population.”

Just this past week—yes, I mean in June 2019, or 56 years after the original Bloody Monday event—Danville’s police chief, Scott Booth, offered a public “heartfelt apology” to the city’s African American community. He did so at an event honoring Apostle Lawrence G. Campbell Sr., a prominent civil-rights and religious leader, who with his wife had been beaten during the 1963 protests. Campbell has recently published a memoir, 1963: A Turning Point in Civil Rights. In it, he points out how inflexibly segregated the city was in his youth, and the aspects that have changed now: a black mayor, a black superintendent of schools, black members of the city council, and overall a city that “is totally integrated, and blacks are very much a part of its growth.” Like other parts of America, Campbell writes, Danville still exists in “two communities, black and white,” especially in religious organizations. But “it’s come a long way” from 1963, he said at this week’s event with Chief Booth.

Why go through this difficult history? On general principles, because it’s true, and because the background of 19th- and 20th-century strife has shaped the social, economic, and physical realities of the town confronting its 21st-century future. Also, I think it’s worth remembering that an imagined golden age in which households depended on big-factory jobs had its severe drawbacks, too.

But in specific, this background is significant in Danville because it helps explain a highly noticeable aspect of modern Danville’s possibilities: the abundance of historic downtown structures, legacies of the tobacco and textile age, that have outlived their original economic function but give the city new prospects today.

“We actually have more antique architecture than downtown Charlotte or downtown Atlanta”— even though those cities are vastly larger, Rick Barker, of Danville, told me last week. Barker, who is now in his 50s, grew up in the area, worked in sales and packaging design for years, but over the past decade has become one of the leading entrepreneurs behind a revival of former tobacco and textile buildings in what is now called Danville’s River District.

“In the 1970s and 1980s, it was popular in lots of places to tear down antique buildings for surface-level parking,” Barker said. “Well, in the ’70s and ’80s, Danville was still a mill town. We had a mill that was thriving, with thousands of employees.”

Then, through the 1990s and early 2000s, the rest of the state took off in a way that left Danville and Southside behind. “At one point we led the state because we had an agricultural-based economy,” Barker told me. “Now, with the booms in northern Virginia, and the Tidewater, and Richmond, we’ve been left out as a mill town in an ag region. And that mattered because [during the recent economic crisis] there was no reason to tear the buildings down. By that point, we didn’t need parking for anything.”

So during one destructive wave of downtown demolitions, Danville didn’t want to tear down buildings, because they were still profitable. And during the second wave, it couldn’t afford to, because it had so many other problems.

“What we tended to do was just cover them up—just put aluminum on top of an antique facade and say it looks ‘modern,'” Barker told me. “Now it turns out that the aluminum was a pretty good protective cover.”

Starting about 10 years ago, Barker and others in Danville began peeling back the facades. The next installment will describe what they’ve found, how they’re paying for it, where they’re aiming, and what this effort might mean for the future of the town.