A view from above

Recently Jim Fallows posted this item on his Substack site, Breaking the News. It is about one kind of everyday calm professionalism on which millions of people depend, but which very few people have the chance to witness or appreciate. It is also connected to the aerial exploration of America that has been a connecting thread of the Our Towns explorations since the start.

Here, with a few updatings, is the account:

For unusual reasons, both family- and business-related, I’ve been almost entirely outside the “virtual” realm and online life for nearly a week.

Deb Fallows and I spent much of that time traveling up and down the East Coast by small propeller plane. We went from the DC area on Sunday afternoon, down to South Carolina, then up to Vermont on Tuesday, and back again to DC recently. The on-scene weather was lovely in most of these places but was challenging in between. For aviation buffs: of the 10-plus total flying hours, about seven were in “actual” instrument conditions—ie, inside the clouds—because of overcast layers along the East Coast. Three of the five approaches-and-landings were also in “actual” conditions.

Being inside the clouds is stressful. (And before you ask, I’ve been doing extensive, recent “instrument proficiency” training flights and check rides, in anticipation of just this kind of travel.) Imagine driving your car with the windshield covered over, and needing to steer, brake, and accelerate just by very precise GPS displays or the Waze voice.

But the long stretches of being inside-the-gray only heighten the sense of awe, appreciation, and beauty when you burst into the clear and can finally glimpse the horizon, terrain, and landscape. That was the case with the approach to Burlington’s airport, as in the photo above. Or the aerial perspective on Cooperstown, New York, home of the Baseball Hall of Fame, as shown in the photo below. (This zoomed-in view makes us look much closer to the ground than we really were. At that point we were still on an instrument flight plan, 5,000 feet up.)

Most of this post will be an aviation report. Here is the reason I go into it, apart from noting our offline hiatus: On this trip Deb and I were exposed once more to an under-appreciated, or mis-appreciated, aspect of America’s “soft skills” public infrastructure. I’m writing this item to convey a view of their work that most people never have a chance to see.

We also were reminded of a specific contrast between U.S. practices in this regard, and those we had seen while living in China.

When the airwaves are raucous, and silent

Depending where you’re traveling by small plane in the United States, and in what kind of weather, you can go for long periods without talking on the radio to air-traffic controllers—or your headset can rattle with more-or-less nonstop transmissions.

On clear days, when flying over farmland or prairie, you might not need to talk with a controller at all. People who don’t know the general-aviation world are usually surprised to learn that, in the right circumstances, you can pretty much take off and go where you want, as in a car. The “right circumstances,” for these purposes, mean: the weather is clear, so you can see where you’re going and can fly under “Visual Flight Rules”; you’re not crossing into restricted or “special use” airspace, which can range from military bases to Disney World; you’re not going too close to big cities and major airports; and you’re not climbing to the high altitudes populated by jets.

When going from city to city in, say, Kansas or the Dakotas, Deb and I would use the radio to announce our departure to other planes at the small airport we were leaving, and do the same to announce our arrival at the other end. In between, we’d just talk to each other. A story of such a trip, in Wyoming, is here.

But if you’re going up and down the East Coast or West Coast urban corridors, or when you’re traveling anywhere under “Instrument Flight Rules,” you’re talking with controllers all the time. In urban areas, that’s because you need permission to go near cities of any size. In the clouds, it’s because the controllers are telling you when to climb, when to descend, where to go.

Through the decades, the back-and-forth with controllers has made Deb, who is a linguist, more and more aware of their precise, spare, specialized grammar and lexicon. She’s written about that many times, for instance here. Through the decades, I think I’ve better learned how to communicate with counterpart terseness.

And we’ve both grown ever more respectful of the practiced sang-froid of controller-culture generally—and also the difference between veterans and rookies at the job. We had reminders of each this week.

The tenser it is, the calmer they sound

The (enjoyable) 1999 movie Pushing Tin portrayed air-traffic control as a kind of bumper-car exercise, in which planes are always about to crash into each other, until controllers veer them to safety. As William Langewiesche—celebrated as a pilot as well as a writer—explained back in 1997 in The Atlantic (“Slam and Jam”), that image mis-represents the controllers’ skills.

While coping with emergencies is part of their training and readiness, including the one in Boston I wrote about recently, most of the time controllers’ duties are large-scale and strategic. The best ones anticipate emergencies that could happen 15 minutes (or 50 miles) into the future, and make the minor adjustments now that avert them.

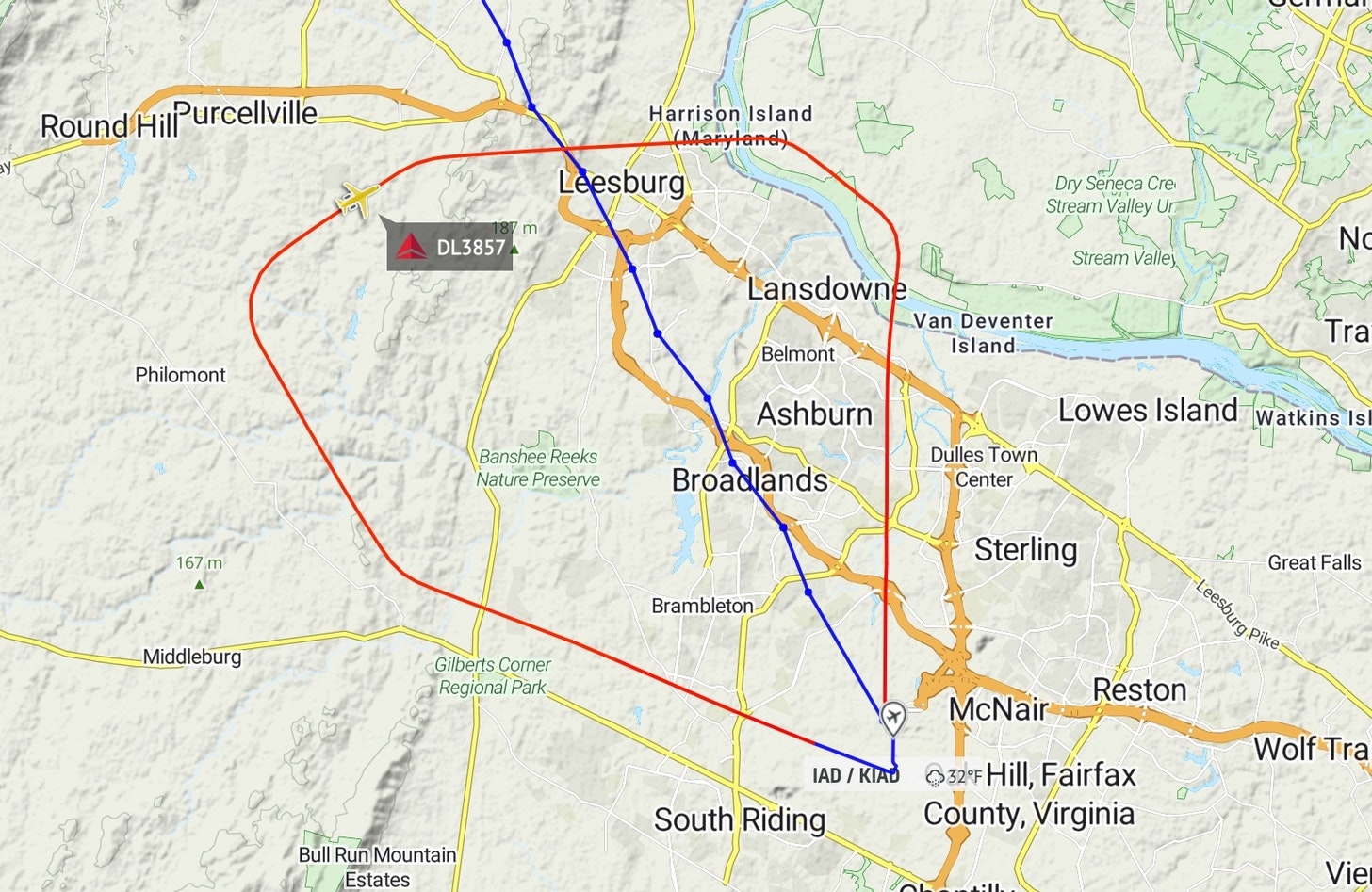

Here are two small illustrations from our recent travel, with accompanying screenshots of the trips from Flight Aware:

—About half an hour before landing in Burlington, the overcast layer had finally cleared, and we could see outside. What was below us at that point was the transition from the very high terrain of the Adirondacks to the low surface of Lake Champlain.

I needed to descend in a hurry, from 7,500 feet over the mountains to around 2,000 feet for the approach. The Burlington Approach controller calmly alerted me to two factors to be aware of as I did so.

One was a sightseeing Twin Otter float-plane doing low-altitude tours beneath me, over the beautiful lake. Because of it, I should be careful to descend only so far and so fast. The other was a regional jet that was waiting to take off from Burlington until I had landed. And because of it, I shouldn’t dawdle in getting to the runway.

This info was relayed in a calm, conversational tone. It was part of the ballet of keeping the sightseeing float plane, our inbound Cirrus, and the outbound commuter flight all aware of one another, and all getting where they wanted as smoothly as possible. Not to mention the F-35s based at the same airport, and helicopters, and a variety of other traffic. (If I can I find the exchange on LiveATC.net, I will post it.)

The other episode was two days earlier, on approach to the main airport in Columbia, South Carolina. Again it was a question of choreography. I had been cleared to land, and a regional jet was ready to depart, but it was nearing the end of its authorized window for takeoff time.

As I headed toward the airport, the controller asked if I could make a “left 360” to delay our touchdown, and give the jet a chance to get out. If I had still been in the clouds I would have said “unable”—or might have asked him for a “delay vectors” heading. But we were in the clear, and I said “affirmative.” We made the turn and bought a minute of spacing time, and the jet was safely on its way. Otherwise it might have had to request a new clearance, with many minutes’ delay and possible missed connections in Charlotte or Atlanta for passengers aboard.

My point once more is that this was a controller who had confidence in his ability to envision, regulate, and safely maximize a flow.

Rookies and vets

When I was writing about China’s aviation ambitions nearly ten years ago, in my book China Airborne, I said that there were two main reasons why airline travel in China is so much slower and more plagued by delay than its counterparts in North America or Western Europe. (Yes, it’s worse.)

One reason is that so much of China’s airspace is still under military control, which forces even airliners to take enormously indirect routes. In the U.S. and Canada, most airspace is available for commercial use, and a small share is hived off for the military. In China the reverse is true. I go into this at length in the book.

The other reason is that fewer of China’s controllers have the choreographic “we can make this work” confidence that William Langewiesche detailed in his article, and of which I am giving small-scale examples from Burlington and Columbia. Their commercial aviation system has gone from being Wild West and highly dangerous a generation ago, to now extremely safe—but with a procedural ponderousness that is different from North American and Western European standards.

One example: at their pre-pandemic levels, the two busiest airports in the United States, Hartsfield-Jackson in Atlanta and O’Hare in Chicago, handled nearly twice as many flights per day as the two busiest in China, Beijing Capital and Shanghai Pudong. There are many reasons for the difference, but a crucial one is the confidence and competence of the U.S. controllers in sequencing inbound and outbound traffic at the maximum safe rate.

To be ultra-clear about my point: It is an enormous achievement that China’s airline system has become so safe. The next step is to become safe and high volume, as in North America and Western Europe.

What’s the relevance here? In our recent travels, we saw the difference between what a confident veteran and a cautious rookie could do. For one of our takeoffs, we were at an “uncontrolled” airport—a small one without a control tower, like the vast majority of the 4,000-plus airports in the U.S. The clouds were low enough that we needed an instrument clearance to depart.

We started the plane, did the pre-flight checks, and radioed to the local air traffic center to request our clearance to take off. In what I thought was a tentative voice, the controller said, “Hold for release, inbound traffic, call me back in ten minutes.” The “inbound traffic” turned out to be a plane that was many miles away, and that touched down long afterwards. The controller was taking absolutely no risks.

I won’t go through all the intermediate steps, which left us on the ground, with the engine running, for quite a while. I’ll just say that there was a dramatic change when a different voice came on the radio. This controller’s first question was, “Are you ready for takeoff with no delay?” I said that we were. She said, “cleared for takeoff, no delay, traffic inbound XX miles away [this was a second inbound plane], report immediately if not airborne,” plus some other instructions.

We took off; the next inbound plane landed a minute or two later; and we realized that we’d witnessed the difference between a controller who was still gaining experience, and one who already had the experience and was confident in her big-picture understanding.

Of course there is no shortcut to becoming experienced. But Deb and I were both reminded of the fully experienced, intentionally calm, orchestrating-and-strategic skills of the women and men who make this part of American life go. Our thanks and respect to them. And we are imagining how many other parts of our society depend on similar day-by-day competence that the rest of us take for granted.