Our Towns co-founders Deb and Jim Fallows visited Marion County in southeastern Tennessee this past spring, and spent time at the exhibit of the Paper Clips Project, a memorial to victims of the Holocaust in Europe, at the Whitwell Middle School. This report tells the backstory of the Project and shows how students can be drivers of conversation and understanding of very grown-up issues.

Taylor McDaniel Kilgore was 10 years old the day a German railcar pulled into Whitwell, Tennessee in 2001. As a student at the Whitwell Middle School, Kilgore locked eyes on the dark brown, wooden railcar rolling in. Many others did the same. News of the railcar’s anticipated arrival brought out the townspeople and invited in an array of visitors with cameras ready to capture the moment in history.

Such an occasion might have seemed strange wherever it happened – a foreign piece of transportation equipment being ported in from more than 4,000 miles away, gathering an eclectic crowd on onlookers. It might seem all the stranger in the small city that’s home to just 1,641 residents in the southeastern Tennessee Sequatchie Valley. But this railcar had a purpose in Whitwell. It would serve as the container for the millions of paper clips that Kilgore and classmates had been collecting over the last three years.

The day the German railcar turned up in Whitwell left an indelible mark on Kilgore. When she came home later that day, she announced to her mom that she was going to be a teacher. More than 20 years later, at the age of 30, Kilgore has since made good on her word, having gone off to college to study education and having returned home to Whitwell to help continue engaging more students in what has become Whitwell’s nationally and internationally renowned Paper Clips Project.

The Paper Clips project, now an educational program and memorial for the 6 million Jews and millions of Jehovah’s Witnesses, Gypsies, and other people murdered during the Holocaust, is now 24 years old. It got started in 1998 when Linda Hooper, then the principal of Whitwell Middle School, realized that she wanted to pursue a project to expose her middle school students to the outside world in a meaningful way.

“I looked around at my kids and thought, What am I going to do to introduce my kids to different cultures and make them appreciate how easy it is to be lead astray and how easy it is to make the choice for evil instead of good?” she told me.

That thought led Hooper to send Assistant Principal David Smith to a conference in Chattanooga presented by iEARN, an organization that empowers teachers and students to work together online. Smith returned to Whitwell with a study on the Holocaust that school leaders modified into a voluntary, after-school class attended by 30 eighth-grade students, each accompanied by a family member.

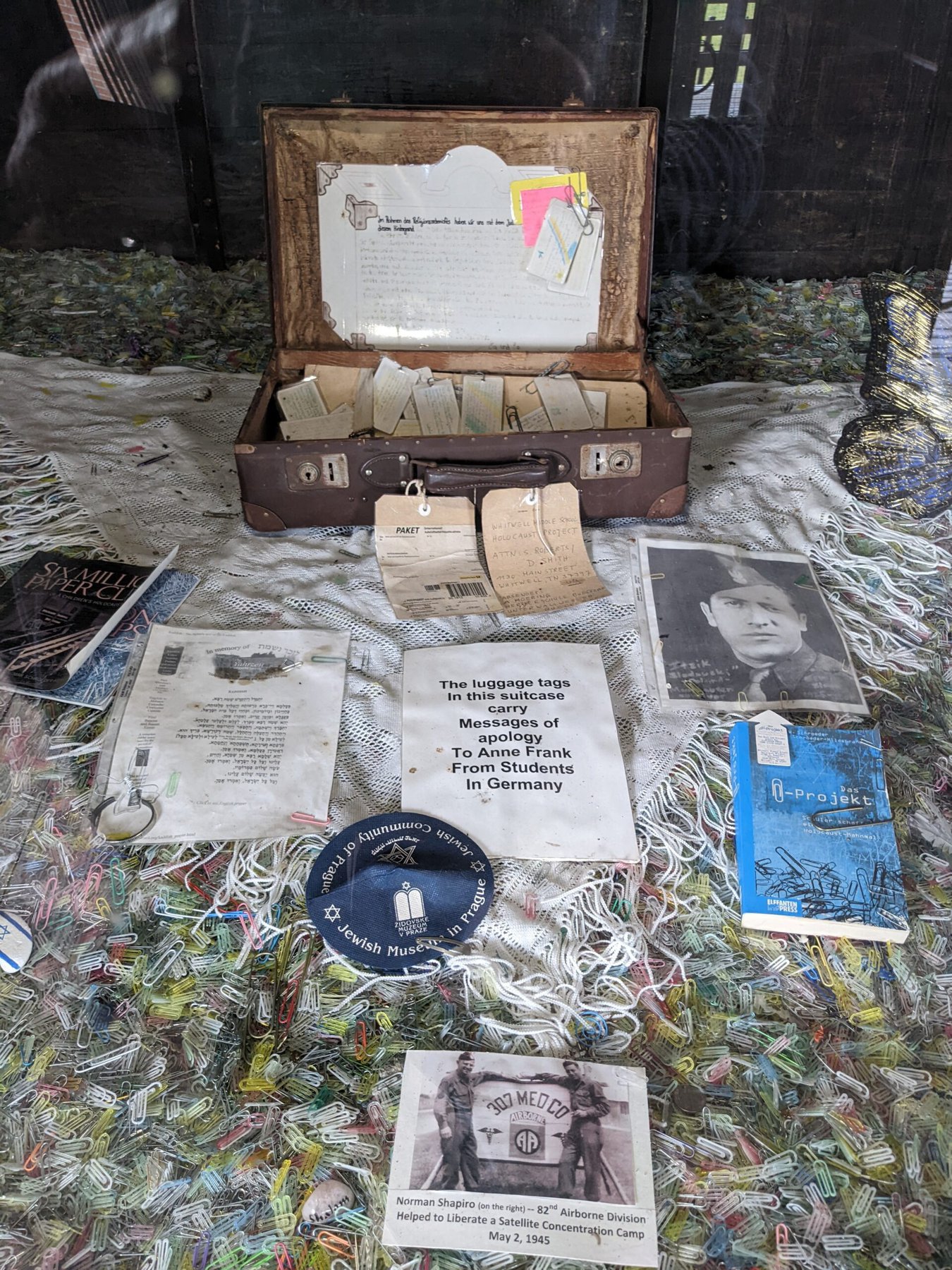

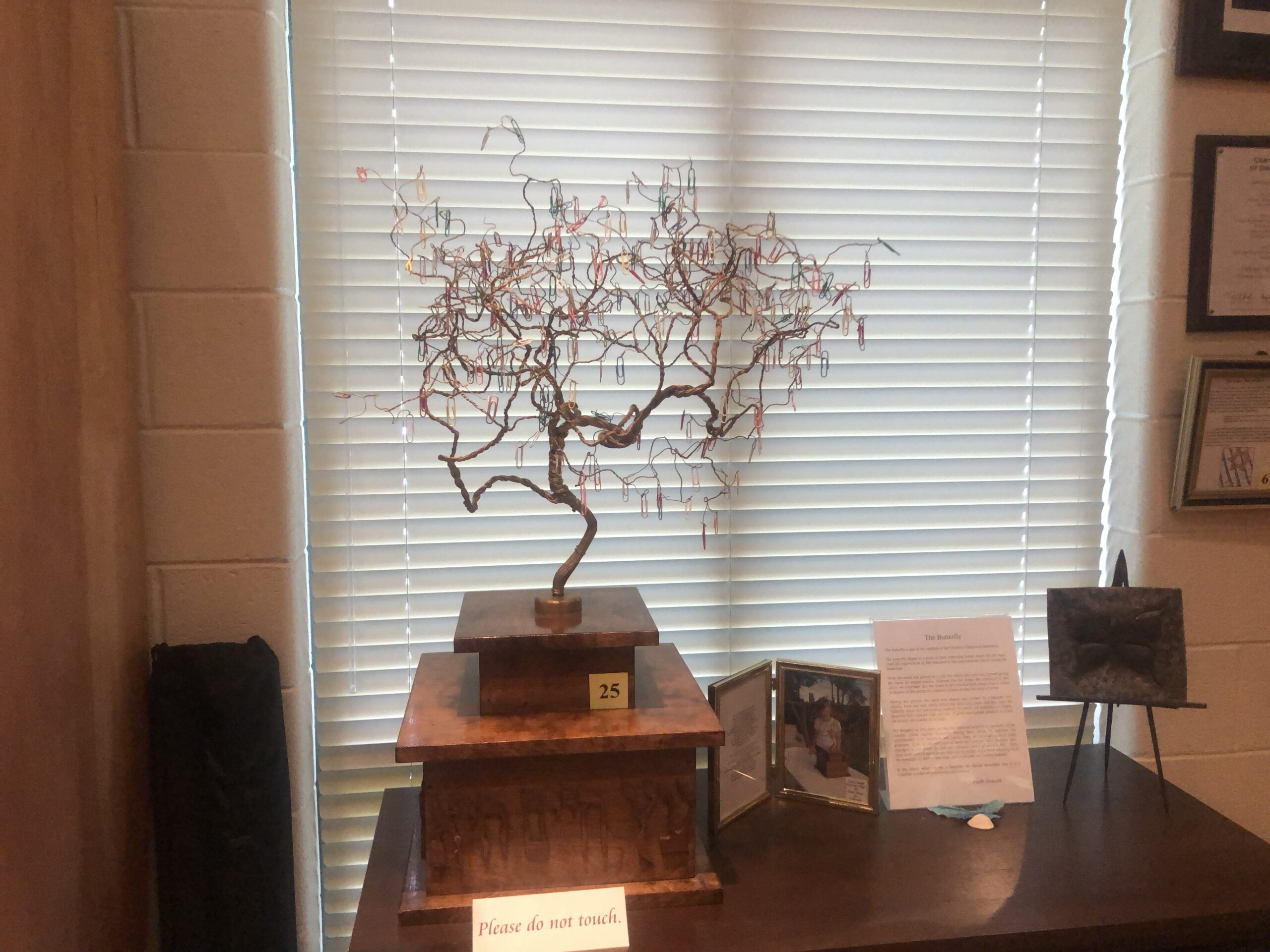

The after-school class was so successful that the Whitwell administration incorporated it into the regular curriculum for the 1998-1999 school year. During that year, a student came to Hooper saying that she had trouble picturing 6 million people. She wanted to collect something that would make the reality more vivid, and represent those killed by the Nazis. Hooper agreed on the condition that whatever they collected would be small but relevant. After some research, the administration chose paper clips, since Norwegians had worn them as a silent protest against Nazi occupation.

The idea stuck, and the school registered the Paper Clips Project with the National Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. Students and teachers also wrote letters to the president, state representatives, and any other person who came to their minds who could contribute to their paper clip-collecting cause.

Progress was initially slow. Then Lena Gitter, an accomplished author, who, in 1938 had fled Austria and the Nazis with her husband and daughter, discovered the project online. She shared it with German journalists Peter Schroeder and Dagmar Schroeder-Hildebrand. The Schroeders visited Whitwell, and wrote multiple articles and a book titled Six Million Paper Clips: The Making Of A Children’s Holocaust Memorial about their experience.

While the Schroeders promoted the Paper Clips Project in Europe, it was Dita Smith’s 2001 Washington Post article, “A Measure of Hope,” that gave the project a national spotlight in the U.S. Within six weeks of her article’s publication, Whitwell Middle School received more than a million paper clips. The article also directly inspired Paper Clips, a 2004 documentary showcasing the project and explaining how the students responded to lessons about the Holocaust.

Having gained awareness, the project continued to prompt a pouring in of paper clips. The big project in the small town created such a response that Hooper told me that she couldn’t even estimate when the school reached six million. It happened rapidly, and the number continues to climb.

That worldwide support led to a new challenge – where to put all the paper clips. The school had been storing them in large barrels in its basement. Then the Schroeders found an authentic German railcar in a railroad museum in Robel, Germany, and raised funds to purchase and bring it to rural Tennessee in 2001. With the paper clips newly on display, the school’s project continued to draw more people to the town.

“One summer, I was in the office working and saw an elderly couple standing in the doorway,” Hooper told me. The visitors had flown from Los Angeles to Nashville, and then drove two hours southeast from Nashville to Whitwell.

“Their only purpose was to put four paper clips in that car – two for his parents and two for hers,” she said. Nazis had murdered the couple’s parents, and they wanted a way to visualize them surrounded by the people who cared for them, Hooper explained. “If we didn’t do anything else, it was worth it for them.”

The railcar soon become the centerpiece for the school’s official Children’s Holocaust Memorial and housed millions paper clips to represent the victims. Visitors came to Tennessee to see the memorial, and Whitwell students traveled to speak in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and all over the United States. Other student groups have toured Germany, Poland, and Israel. Hooper even mentioned one group that met with Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu in South Africa.

After the Paper Clips documentary showcased the origin and early years of the project, the momentum continued. The project stopped counting how many paper clips they received after 30 million, and it still receives visitors and letters to this day. Aside from a pause caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, eighth-grade students have been continuously trained to lead tours for visitors.

Hosting students from other areas is particularly important for the Paper Clips Project. According to Kilgore, teaching and showing kids that everybody can find some common ground is a major focus. This goal was a big reason why Whitwell Middle School hosts a group of eighth graders from Lower Merion Area Hebrew High, a community program for Jewish teenagers in grades 8-12 from four synagogues around Philadelphia. The relationship began after Norman Einhorn, the Lower Merion program’s director, introduced himself to original Paper Clips Project teacher, Sandra Roberts, at a speaking engagement. That conversation led to a tradition of visits that has lasted for more than a decade.

Every year, a group of mostly eighth-grade students and parents from Lower Merion will spend a few days in Whitwell to tour the memorial, share meals with their Whitwell counterparts, and have fun together. This experience allows the children to meet people who come from different backgrounds and to interact with each other.

“It’s just proof that if you let kids be kids, they’re not going to see the things that we see as adults,” Kilgore said. “Those are friends for life that these kids are going to have no matter where they go in life, whether they stay home or go to college. There’s somebody not from their hometown they know they can reach.”

The Paper Clips Project also inspired the creation of One Clip at a Time, a Chattanooga nonprofit that promotes student activism. Educators across North America can attend events virtually or in person to learn how to encourage kids to actively address problems in their own communities. Part of that process includes giving the children the opportunity to make a difference.

“What I tell everybody that comes in here is: ‘Never underestimate a kid,’” Kilgore said. “It doesn’t matter if you are from Tennessee or California, wherever it is. We have a perceived notion that we’re supposed to teach kids and they’re not supposed to know anything except what we tell them. If you get that out of your brain, and you let them be kids, you might be surprised at what they can come up with.”

Our Towns has reported on a number of initiatives around the country where students drive change in their communities. In Winchendon, Massachusetts, students were concerned about sexual orientation discrimination and managed to write and lobby for passage of a citywide proclamation to recognize National Pride month as “a way to promote the principles of equity and liberty.” In Columbus, Mississippi, high school students annually write and stage re-enactments of Civil War era daily life and issues to open conversations around race among the biracial population of their town.

From Tennessee to Mississippi to Massachusetts, students are studying and learning about ongoing issues in their towns, and demonstrating that they can be influential part of civic life to address those issues.