There is a category of things you “learn” from travel or other experience that you simply weren’t aware of before. Example: it is obvious once you travel around in the Dakotas that they really should have been two states — but East and West Dakota, not North and South. And that the political dividing line should have been what is also the natural and geological and climate-zone divider, the Missouri River, which in that part of the country runs largely north-south. Obvious once you see it, but something I had not thought about before.

A different kind of learning involves things you already “knew” but whose implications and importance you had not really absorbed. One more of these reminders from Holland, Michigan is the crucial impact on civic culture of locally based wealth.

Of course everybody knows that family- and personally owned businesses can behave differently from publicly traded firms. For the big corporations, it is a compliment rather than a criticism to say that ultimately they care most about dividend growth and “maximizing shareholder value.” Toward that end layoffs, outsourcing, cost-cutting, cheese-paring, union-busting — you name it, and if it can arguably lead to greater long-run corporate profitability, then by definition it is what management should do.

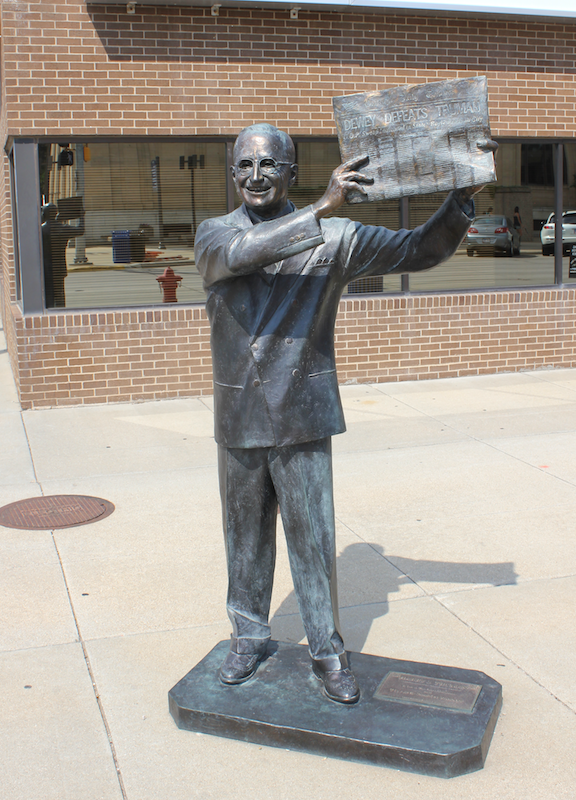

A family or privately run business can do things differently, for better and worse. Worse: management jobs for relatives, whether competent or not. Better: deciding in some cases to take a temporary loss, or settle for less-than-maximized profit, in exchange for some other goal. Through its decades of collapse, the newspaper industry has illustrated these tradeoffs. Family ownership has led to its excesses: Hearst, McCormick , Murdoch. But also to some great ambitious traditions: Binghams (until they sold), Chandlers (until they sold), Grahams (until they sold), Sulzbergers (….), etc. By the way, that’s part of the McCormicks’ legacy shown in the photo, via life-sized recreation in Rapid City SD’s “City of Presidents” outdoor-art display.

What’s the connection to Holland? Like everyplace in America, its economy is tied to international trade and big global corporations. Many of its strongest manufacturers make auto-industry and aerospace components. Haworth, Herman Miller, and nearby Steelcase sell into the world office-furniture market. The Padnos family’s scrap and recycling company, mentioned earlier, has big markets in China. The Amway corporation, founded and run not far away, is of course a global titan.

But an unusually large amount of Holland’s economic activity comes from companies that have their headquarters right in the vicinity, or are still owned and run by people who live in the immediate area. And every single person we spoke with emphasized the difference that this awareness of local circumstances, this involvement in local long-term prospects, and this latitude of policy for family-owned companies made in the region’s life.

Not always in a positive way. A big local flap involves descendants of the two enormously rich Amway-founder families: the DeVoses and the Van Andels. That’s a controversial new Van Andel mansion in the picture, going up inside a gate-protected community but with a commanding prospect on the nearby public beach.

On the one hand, the two families’ philanthropic mark is everywhere. We saw the vast DeVos Fieldhouse sporting complex at Hope College (which is part of Holland’s downtown) and met people who worked at the nearby Van Andel Institute, a medical-research center. On the other hand, the DeVoses have played a big part in right-wing politics, and one of the Van Andel descendants is involved in what seems an almost feudal dispute, also related to the house shown above. Short version:

One of the city’s landmarks, a picturesque Lake Michigan lighthouse named Big Red, sits on public land. But the road to it goes over the property of a Van Andel family member who has decided to grant the public access to the lighthouse on only two days per week. You can read more about it here. The photo at the very top of this post shows how Big Red looks from the private side. Here is how it looks from the public Holland State Park beach on the other side of a channel.

(Another group of young men, just out of this shot to the left, were happily passing around a joint on a summer Sunday afternoon.)

I know enough about other towns with inescapable Leading Families to understand that not all of their influence is positive or comfortable. However. Time and again in this little city we came across evidence of local industrial families pitching in for the city’s development. For instance:

- The late Edgar Prince, as mentioned in the “snowmelt” saga, personally organized and partly bankrolled the snowmelt system and other parts of downtown Holland’s restoration. “Mr. Prince and others thought it was very much in their interest to create a dynamic downtown,” Randy Thelen, from an area-development group called Lakeshore Advantage, told me. “Prince was a huge factor in improving the downtown,” Jim Timmermann, opinion editor for the Holland Sentinel, said. “He bought up properties and held onto them until he was confident that the right purchaser or tenant had come along.” Prince’s wife is still involved in downtown-development work.

- At the Arts Council, the symphony, the museum, the colleges, and almost any other civic site you can mention are plaques acknowledging gifts from the same list of local family-business names.

- In the public schools system, and at the private-religious Hope College (right), we heard repeatedly about the networks and programs locally based businesses have created, to place graduates in jobs.

- Local business families have also been leading a lake-cleanup effort, and a community energy-efficiency program.

- There was an interesting dog-that-didn’t-bark counter example. The enormous downtown Heinz pickle works is the oldest major factory in town, and the biggest pickle works in the world (below). It employs many, many more people than, say, the Padnos scrap works, but has a much lower civic-leader profile. The obvious reason is that the Heinz family and the Heinz company are from, and of, Pittsburgh, not any place in Michigan. In their real home, the place the founders and descendants cared about, they have a big effect. Much less so here.

“What makes the city what it is?” Jim Timmermann, of the Sentinel, said when we talked with him. Timmermann grew up in Southern California but came to Holland with his wife, a Hope College professor, in the early 1990s.

It’s because of the local entrepreneurs who:

• Started their companies here;

• Kept them here, when they could have moved away;

• And remained active in the community, all of this when they could easily have moved away.”

OK, he didn’t use bullet-points when he was talking, but I wrote it down that way. “The involvement by leading families here has been crucial, and I’m not sure that it is replicable,” he said.

To conclude: You “knew” all this already, as I did before going to Holland. But after our visit there I realized how inured I’d become to the idea that companies would always and only run on a Gradgrind-style shareholder-value basis, and that they would be “from” no physical location except the stock exchange. I’ve been looking at local ownership and local influence differently since our time in Holland.