Flying into Columbus, Ohio a few weeks ago, we chose to land our Cirrus SR22–yes, the one with a parachute built into the fuselage of the plane—at Rickenbacker International Airport (call letters KLCK). How could we not? The namesake alone would be enough to attract us: Eddie Rickenbacker, Columbus native and renowned World War I fighter pilot. Besides that, the airport has two 12,000 foot runways (longer than any at LAX, for example), built in 1942 for pilot training and support for the Army Air Corps. Today it is used for cargo, air charters, air shows, and various Ohio National Guard and defense systems, and general aviation aircraft like us.

I found out about another flyer from Columbus, an aviatrix named Jerrie Mock. I was puzzled, and a bit embarrassed that I hadn’t heard of her before. Formally Geraldine Fredritz Mock, she was the first woman to fly alone around the world. Alone! Around the world! In her single engine four-seater Cessna 180, in 29 days in the spring of 1964.

How had I, a kid in northern Ohio then and stuck on Amelia Earhart from an early age, missed that? Well, as I learned from my recent casual polling, I was far from alone in missing Jerrie’s adventure and not recognizing her name.

But think about it; it makes sense that we all knew of Amelia. When Earhart was flying in 1937, it was the between-the-wars Golden Age of Flight. Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic nonstop in 1927. There were air races, barnstorming, round-the-world flights. Commercial airlines began, including luxurious (!) long-distance flights. There were dirigibles and seaplanes. Amelia was a natural for the era: dashing, adventurous, and modern. She had a great silver plane, a Lockheed Electra 10E, and married savvy book publisher and publicist extraordinaire George Putnam.

By the 1960s, the Space Age had arrived. We were chasing Sputnik and looking at pictures from the far side of the moon. Science was about rockets and computers. Astronauts like Alan Shepherd and John Glenn were king, and the universe beyond earth took over our imagination.

So, what did we miss by missing Jerrie Mock?

Jerrie was a mix of unconventional and conventional. She was interested in flying even as a child. She studied aeronautical engineering at The Ohio State University in 1943. She dropped out to marry, had two kids and later a third. She earned her pilot’s license at 33, flew around when she could afford it, and managed 3 FBOs, the small general aviation terminals. In the 1950s, Jerrie addressed her self-described boredom by talking about a big flying adventure. In a “Why don’t you just do it then!” conversation with her husband, who was also a pilot, she decided to try to fly around the world. By 1963, when Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique was published, Jerrie Mock was well into her 18-months of preparation for her round-the-world flight.

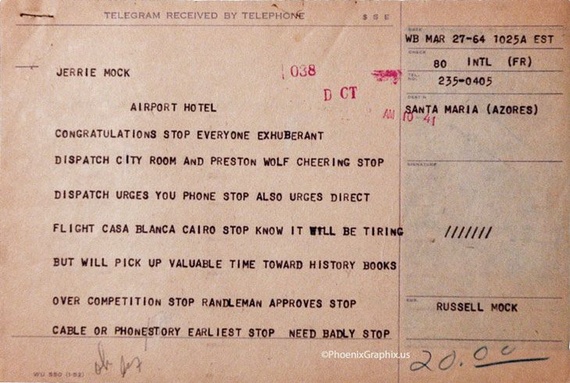

Her husband, Russ, bought a half share in a Cessna, which she pluckily named Spirit of Columbus, in Lindbergh model of Spirit of St. Louis. She and Russ made several trips to Washington, to secure visas for countries along her planned route, and to file her intentions for the record-setting flight with the National Aeronautic Association (NAA). Russ upgraded the plane for the long journey, sought sponsorships and supporters (Interestingly, Cessna wasn’t interested.), and they arranged for Jerrie to chronicle her flight for the Columbus Dispatch. She flew and trained, securing her instrument rating just shortly before her scheduled departure.

A last-minute instrument rating (IFR) sounded very last minute to me, and I asked Dale Ratcliff, an experienced pilot and aircraft mechanic and technician, who recently spent many, many hours talking aviation and airplanes with Jerrie, about it. Ratcliff’s interpretation was that she prepared well before that, and wanted to take the tests then to be as fresh as possible on procedures and practice.

Ratliff vouched that even in her 80s, Jerrie’s breadth and scope of knowledge about planes, their mechanical systems, the complexities of flight, and the rules and regulations of procedures left no doubt about her expertise. By contrast, Dorothy Cochrane of the National Air And Space Museum, said that Amelia Earhart hadn’t even bothered to learn Morse Code, an important navigation tool at the time. (Cochrane wrote excellent blog posts about Mock hereand here.)

And just as important to her success, Ratcliff pointed out, Jerrie Mock was relentlessly methodical, logical, procedural, and possessed a keen situational awareness. She would need that.

On March 19, 1964, Jerrie departed Columbus for Bermuda. All her flights were long, and this one, her first over-water flight ever, was no exception. Past Richmond, Virginia, she unreeled her 100-foot trailing antenna to catch the high-frequency radio she would need over the Atlantic. She tried calls to New York Oceanic, the over-water contact. No response. She tried every possible radio fix with no success.

She wrote in her book, Three Eight Charlie (the call numbers for her plane, which she affectionately called Charlie), about the incident:

The radio just had no power. It was as if it were disconnected.

Now what should I do? Go home? Land at Richmond? I thought of the crowd back in Columbus. I thought of the sponsors who had risked their money on a flying housewife. Those people believed in me. How could I let them down?”

Calling Norfolk on the over-land VHR frequency, she reported in one last time, telling them that she could make no contact with New York Oceanic on her high frequency radio. She wrote of the garbled communications:

I stood by, listening to that channel, hoping that I’d be out of range before someone told me to turn back.

“38 Charlie, Norfolk Radio.'” The transmission was faint, barely readable. I didn’t know what he was talking about. Fading swiftly. One word: “…hatbox.”

Hatbox? What was I supposed to do with that?

And off she flew. This, I think represented what Ratcliff was describing as the balancing point between Jerrie Mock’s being extremely prepared and being, as he described her, “a calculated risk taker.” This balance strikes me as familiar among the pilots I know. Flying is more dangerous than lots of other pursuits, of course. Unexpected things—weather, mechanics, other planes, you name it—arise surprisingly frequently. But pilots I know and respect share the traits that Ratliff uses to describe Jerrie.

Jerrie landed in Bermuda in fierce winds, which increased soon to 75 knots, hurricane strength. She was stranded there for a week, but it gave her time to have the radio checked. With much trouble, mechanics removed the 110 gallon tank next to the pilot’s seat. (All 3 extra seats had been replaced with gas tanks.) She wrote of the mechanic, who was tracing the wire from the radio:

In less than a minute he sat up and looked at me with a funny expression on his face. “Well I found the problem, and it’ll be easy to fix. But I sure don’t understand the men who installed the radio.”

The wire had been disconnected at the control head—deliberately, they figured. It was a mystery never resolved.

Mock encountered other episodes that seemed scary to me, and which she seemed to handle with the same calm and confidence: icing conditions over the dark Atlantic; mild sandstorms over the Arabian desert, failing brakes, unexpected weather changes, navigation equipment challenges.

There was one other thing she couldn’t control. Jerrie’s adventure became a race when Joan Merriam Smith, another pilot, also planned to set off on her own solo adventure to circle the globe. Mock had no choice really but to get caught up in the competition. Her book is seasoned with repartee between her and her husband about the pressure it imposed.

Russ managed to track Jerrie down, no matter where in the world she landed. Their exchanges sounded testy. The call in Bermuda, where she was finally stuck for a week, was typical of how she portrayed Russ:

Look, weather can’t be that bad for that long! Woman, you have to fly. That’s why you got an instrument rating, so you could fly through fronts. Joan’s leaky gas tanks are supposed to be fixed now, and the wire services say she’s ready to go on. She’ll get way ahead. Remember your sponsors, and take a few chances.

Being in a race meant that Jerrie passed up adventures she wanted to do. You can hear the poignancy in her writing that she could take only five minutes—five minutes!—at the Pyramid of Cheops. Or that she couldn’t stop to see the Taj Mahal, or even overfly it for a glimpse because it fell within restricted air space. She was forced into taking time for some absurdities, which amused her: Upon departing Cairo, an immigration official repeatedly insisted that he couldn’t clear her to leave until she produced an airplane ticket. Explaining that, actually, she didn’t have a ticket since she was flying her own plane, did not persuade him.

Jerrie did complete her adventure and finished the “race” first. Joan Merriam Smith had met with more weather delays and mechanical issues, which slowed her down. (And a sad footnote, Joan Smith died in a small-plane crash in the San Gabriel mountains about a year after she completed her own circumnavigation.)

Jerrie Mock was showered with awards, proclamations, and medals, even from Lyndon Johnson in the Rose Garden. She reportedly never gained an appetite for the limelight, shunned speaking engagements and public appearances. She continued to refer to herself as a “flying housewife,” which always reminds of how Senator Patty Murray first referred to her candidate-self as a “mom in tennis shoes.” But she achieved exactly what she sought, a huge flying adventure.

I think of Jerrie Mock now as one who slipped away from us. She died on September 30, 2014, at age 88. She had lived long enough to enjoy the 50th anniversary celebrations of her aviation milestone at the Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum. And fortunately, we have ways to catch up with her. Here they are:

The book: Three-Eight Charlie, by Jerrie Mock, available from Phoenix Graphix Publishing Services, including a 50th anniversary edition. Wendy Hollinger, owner and publisher, here.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Fly38Charlie

See the plane: at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at the National Air and Space Museum.

See the statue: at the Port Columbus International Airport, Columbus OH

Maybe more will appear later, if the packets of records, dispatches, and memorabilia she sent home to Columbus from various stops around the world ever arrive.