This post is about three recent developments that bear on a common theme: the complex role of “place” in Americans’ identities.

It’s a theme that ran through the entire Our Towns book and our movie, and that Deb Fallows recently addressed in a dispatch from Florida. My latest report on the contradictory strains of where-ness in American life was here.

In short: the importance of place comes from people’s lasting sense of where they are from, and their emerging sense of where they would like to be. Some times these turn out to be the same place: It matters deeply to walk your children down the same streets where your parents walked with you. Some times they turn out to be the other side of the country. Consider my current-favorite California movie, Ladybird, or Mona Simpson’s first novel, Anywhere But Here.

The theme is rich, and it’s complicated, and it’s the back story of our on-the-move but also-rooted country. Here are three reasons it’s on my mind. [Note: this item is co-published with the Breaking the News substack site.]

1) William Whitworth, an Arkansan on the East Coast.

Last week William Whitworth, universally known as Bill, died in Little Rock, at age 87. You can read a beautiful appreciation of his achievements, and his quirky humanity, in this brilliant Atlantic piece by two people who worked closely with him, Cullen Murphy and Scott Stossel. Ian Frazier, of the New Yorker, also wrote wonderfully about Bill here. Bill had been the boss, editor, lodestar, and friend to all of us and to countless others in the writing world. I feel so fortunate to have been part of his time at the Atlantic. I will miss him every day. And I won’t presume to add to the portrait that Cullen Murphy, Scott Stossel, and Ian Frazier have collectively created.

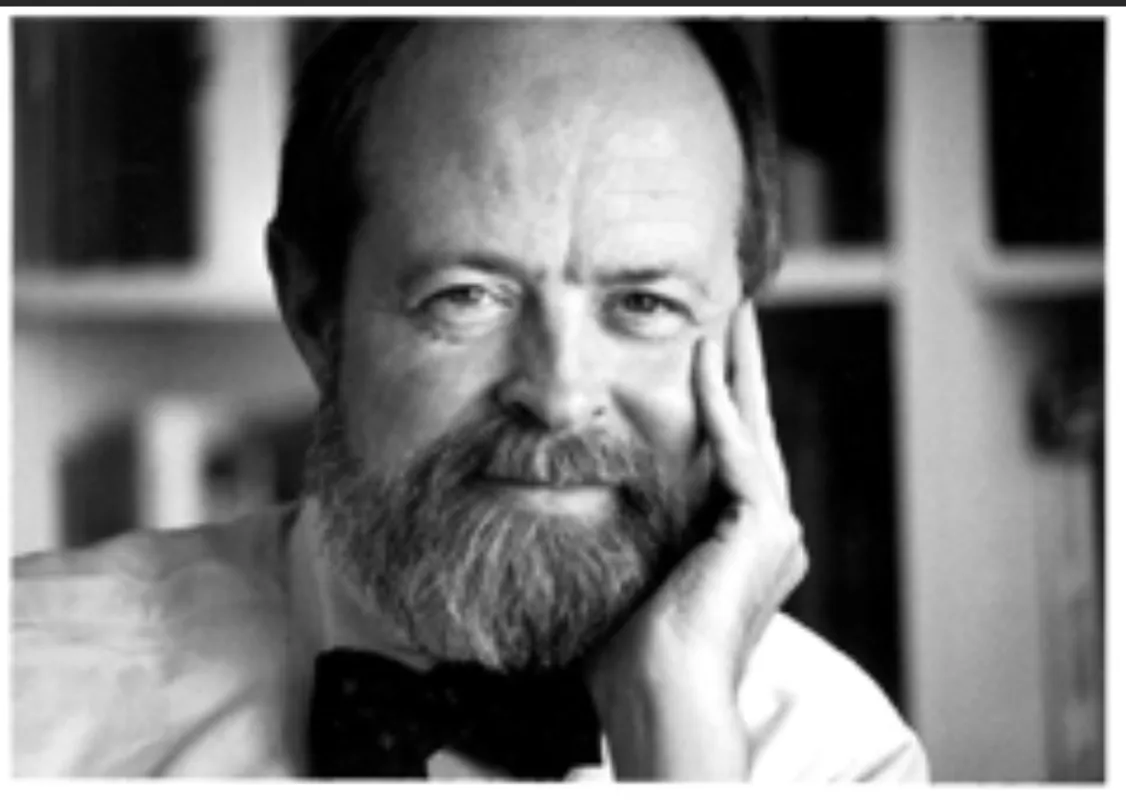

Below is a literal portrait of Bill Whitworth, as I first knew him in the early 1980s. This photo has accompanied countless pieces about him. It would have been at the end of his time at The New Yorker or the beginning of his Atlantic run, when he was in his early 40s.

What’s the place-connection here? It is that Bill Whitworth—who as “William” had a dominant role for two decades as a New York and New Yorker writer and editor, and for two decades more as dean of Boston/East Coast journalism from his seat as revered Atlantic editor—was always from Arkansas.

He grew up there. He graduated from Little Rock Central High School, famed for the 1950s desegregation order. He began his newspaper career with the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. And when he ended his run at the Atlantic, as David Bradley bought the magazine and brought in Michael Kelly as editor, Bill returned to Little Rock and spent the rest of his life there. The headline in ArkansasOnline last week read:

Arkansas’ Bill Whitworth dies at 87; was editor at New Yorker, Atlantic

The first line of the appreciation by Cullen Murphy and Scott Stossel is:

William Whitworth, the editor of The Atlantic from 1980 to 1999, had a soft voice and an Arkansas accent that 50 years of living in New York and New England never much eroded.

We are all from somewhere. Bill was from Arkansas, and was aware of that identity while leaving his mark much more broadly—including on the minds of his readers, and in the hearts of those who worked with him. I don’t think I’d ever seen him happier than when he was leading a contingent of Boston-and-DC-based Atlantic staffers for a sit-down interview with then-candidate Bill Clinton, at the Governor’s Mansion in Little Rock in 1992.

2) Tom Ruby and ‘Life on the Knob,’ in Kentucky.

Last month I had a podcast conversation with my longtime friend Tom Ruby about these issues of purpose and place.

You see Tom and his wife, Laura, in a photo at the top of this item, outside their house in a small community in rural Kentucky that is set in geological features known locally as “the knobs.” Tom had arrived in the US in the 1960s as part of a Serbian refugee family; grew up, like me, in Southern California; had a long and varied career as an Air Force intelligence officer, with postings around the world; and about a decade ago decided with Laura to begin their next life in rural Kentucky.

Deb and I visited them at “the knobs” two years ago. I’ve been in frequent touch with Tom Ruby about the contrasts between the world he sees there and the perspectives he hears from the rest of the world. Two years ago he wrote a trenchant Our Towns post on how the possibilities for a “next Civil War” looked from Kentucky.

In the conversation below, Tom Ruby touches on a number of points, but he mainly stresses that concentration on the local, and the practical, is the most reliable course through these fractious times.

You can listen to the whole discussion at the Substack site. Note: I was partway through a really bad cold and sore throat when we recorded this, as you will notice immediately.

I offer a transcription of one central point of the conversation below. The full conversation follows at of this post.

James Fallows: I’m going to ask you a personal and local question, before some bigger picture questions. Personally, what’s the biggest surprise you and your wife and your family have had? Something you didn’t expect about living on ‘the knob’ in Kentucky that you hadn’t foreseen?

Tom Ruby:

I didn’t think that it was going to be as cosmopolitan as it actually is. We live in a red county, but even the red is very purple, if that makes sense. So it’s very interesting to me that if you try to bifurcate something into a one or a zero–a red or a blue–well then you can say yes, we live in a red county. It’s very reassuring to me how purple the county actually is.

So people that vote blue do things that you would consider red, like shooting guns out here. My sister-in-law, the first time she came from California on a Saturday morning, she says, What is that noise? And I said, people are out shooting. And she says, At what? And I said, I don’t know, targets, I guess. Why? Because they live in the county and they can. Are they hunting? No, they’re just out shooting…

And so it’s very interesting that even people that vote blue like to come out and shoot guns, and they even come out and hunt with us. The people that consider themselves red, they like to go to the brew pub, they like to go to the Centre College Performing Arts Center to see the shows that come through. It’s very purple.

The full conversation is available as the transcript that I will post below.

3) Arts and Inclusion, in California’s Central Valley.

Early this month the NPR program Here and Now reported on another side of the American saga of place: People imagining where else they could or should be.

This was a five-minute report by correspondent Jon Kalish, which you can listen to in full here, or in the clickable embedded version below:

The headline on the item is “Bay Area creatives find harmonious synergy with their new rural neighbors.” It’s about how people who have been priced-out of San Francisco or Oakland are finding new possibilities and new homes in farming communities in parts of the San Joaquin River watershed known as “the Delta.”

Deb and I had seen this same phenomenon, starting almost ten years ago, in the Central Valley capital of Fresno. For instance in this post, “Creating America’s New Bohemia in an Unexpected Locale,” we talked about how more than a decade ago artists priced out of the Bay Area were finding a new creative home in Fresno and places like it.

An important theme in the Here and Now story is the freedom-to-reinvent that many of the new arrivals feel. For example, Kalish quotes a woman named Heidi Petty, who manages a watershed, runs a cattle range, and does other projects as well. She says, “If you’re willing to try things, the Delta will let you try them… I think the Delta changed who I was. It made me realize that there were new things I could do.”

Bill Wells, of the California Delta Chambers and Visitors Bureau, said, “I think everybody has a kind of the attitude of, Mind your own business up here.” One way I read this was: If you started talking with your new neighbors about national politics, you’d likely disagree. But there are a lot of other ways you can live together.

Kalish packs a lot into these five minutes. And his report reminded me so much of what Deb and I had seen in so many other communities remaking themselves through art and other attractions, from Ajo AZ to Eastport ME. Very much worth listening to.

How we think about where we are from has been an eternal issue of US discourse. I offer these episodes as this moment’s discussion of an ongoing theme.

Transcript of Tom Ruby discussion

Via the magic of AI, here is a transcript of the discussion with Tom Ruby in February.

James Fallows

Tom Ruby, it is a pleasure to be able to talk with you again to continue the discussions we’ve been having over the years. I will tell our audience a little bit about how it is you know and have thought about the things we’re going to be talking about.

But I’d just like to ask you as an introductory question. We’re talking as I’m in Washington, DC with a mid -February snowstorm, and you are in small-town Kentucky. You have been all around the world in your career. Why are you in small- town Kentucky right now? What’s the story of why you are where you are?

Tom Ruby

It did snow last night. We had a really nice covering of about an inch and a half of snow when we got up this morning. And so it looked beautiful in the sunrise. It’s going to melt this afternoon. It’s great to talk to you too, Jim.

We were introduced by our mutual friend, Bob Deans, who was the president of the White House Correspondents Association. And he thought that you and I might have some common interests, and we have for many, many years. So I’m very grateful for those years of fellowship and friendship with you.

Why am I in small-town Kentucky? I live out in the county in the knobs of Kentucky, outside of Danville, Kentucky, which is an hour southwest of Lexington. And we’re here because out of all the places that we’ve lived around the world, we thought the bluegrass was the most beautiful and genuine place that we’d ever lived.

The Air Force sent me to graduate school to get my doctorate at the University of Kentucky in political science and international relations. And in the time that we lived in Lexington, we thought that this was just the ideal place. It had all of the culture that we had seen in DC and Europe and Japan.

It had a great restaurant scene, a great university town, but it was also very, very local. It had everything that a big city had, with tall buildings and skyways between them, but then it also had beautiful little neighborhoods and within minutes you could be out in the countryside.

We went a little bit farther outside of Lexington. We are just outside of the town of Danville. It’s even a smaller place with only 18 ,000 people in the town, but it has a wonderful college, Centre College. It’s a small private, liberal arts school. And Danville itself is like a tiny little Lexington. It has a great restaurant scene. It has a couple of microbreweries, several distilleries.

It has a wonderful school system, the Boyle County Public Schools. And the land here is ideal. When you look at pictures of the place, people just don’t believe that you can still buy land in America that’s close to town, that’s affordable with good schools. And I’m here to tell you that it is.

So we made a decision that this was where we were going to live forever. Or for the rest of our lives. We were going to build a house here when I retired from the Air Force, and start a business. And by that point, two of our kids had already graduated and gone off beyond college. But we still had two more in the house that needed to go to high school. So we integrated ourselves into the community fairly quickly and into our little village up here on the knob, which you visited.

Fallows

And so part of what I think would be interesting for people to hear is, you’ve had a very cosmopolitan background. If I understand it correctly, you, like me, grew up in Southern California. You, like me, have been all around the world on various professional assignments. But for you, unlike me, it’s been through the Air Force.

I’d like you to talk about the difference between the place you are in now, and that you’ve decided to make your long term home, and the way you see places like this described, portrayed, either disparaged or idealized in the national media or the national political discourse. What’s the difference between the world you live in and the world you hear portrayed from outside?

Ruby

I think I’ve been looking for the exact quote forever. I can’t find the exact words. But I’ll paraphrase Chesterton when he said the idea of a thing is very different from the thing itself. And the idea of where we live is either disparaged, or it’s idealized. And it’s neither one of those things. It’s something entirely different.

When people say that there are no jobs in small-town America, it’s just not true because it’s hard to find people to even work, you know, around here. You can go into any place in town here and get a job. When you hear people say that homes are not affordable, well, they’re affordable here.

And what they really mean is that homes aren’t affordable … where I want to live. I saw somebody this morning on Twitter that was disparaging Cincinnati. They’re from New York. And they said, I could never live in a heckhole like Cincinnati because I could never make what I make here in New York City. And there’s no jobs in Cincinnati.

Of course there are jobs in Cincinnati. Of course you could afford to live there because, no, you wouldn’t make as much as you make in New York City, but the delta [difference] would probably make you wealthier than you are there.

Fallows

And Cincinnati, by the way, is a great town, but that’s a whole different topic.

Ruby

But it goes to what you were asking about. The reality of where we live is not the idealization that some people that have of what living in the country is—that it’s just magnificent. Well, it’s still hard. The whole “Cottagecore” concept is not the reality of having a garden. You actually have to dig hard to make your plants grow. And yes, you can feed a family on a garden, but you’re going to be working really hard. And yes, you can do that while working another job.

But there is a reality that’s different from both the idealization and the disparagement. We planted an orchard when I retired from the Air Force in 2012. The house we started building in 2011. You’ve seen it, we have an orchard, it produces fruit.

But we were in it for the long haul. So instead of buying mature trees, which were very expensive, we bought small whips.

We put them in the ground and figured if it takes six years before we get our first fruit, that’ll be fine. And now, when we do have a bumper crop, we send out a text in the group chat to everybody here on the knob and let everybody know. And people day after day with huge buckets and just pick all the fruit that they want to. And nobody has to schedule the time.

But that’s the reality that’s very different from the discussion.

Fallows

Let me ask about a particular point, which has been a through-line in national political discourse about smaller communities, especially over the last decade during Donald Trump’s rise to power. That is the idea that that small places are overwhelmingly exclusive, and resentful. Their resentment is both against “the other” and against perceived helplessness in life. What do you think when you’re in your little community on the knob in Kentucky, when you hear these portrayals, and what would you like people to know about the view from your community?

Ruby

It’s interesting, you know, we have a self -described Daoist shaman here on the knob who, contrary to perhaps popular expectations, you wouldn’t expect him to be a left -wing survivalist. How’s that? We have a lesbian couple here on the knob that are very close to us who have horses and guns. Okay, we have MAGA supporters who don’t wear the red hats, but vote that way. And they get together and host the barbecues for the knob. We have atheists, we have Catholics, we have evangelicals, and they all get together, probably three or four times a year.

We just had a chili cook -off. We had a knob-mob chopped championship [see TV show] where they actually brought in judges and People did like a chopped competition from TV together We do a Christmas get -together. We do a pig roast in the fall or in the summertime.

It’s absolutely not like what you see portrayed in either Fox News or MSNBC. It’s nothing like that. And if those people could see what it was like here, well, you’ve seen it. You came and did a whiskey tasting here. You’ve met these people.

Fallows

We were there just for a day, but it was fabulous.

Ruby

Yeah, it’s nothing like people like people portray.

Fallows

And just to push on that for a second. So as we’ve discussed, over many years when my wife Deb and I were traveling around the country to do our towns reporting and a book and then the film, our version of what you’re describing is similar.

And we found that if you asked people about national politics in this polarized era, then essentially you were going down a hole. There was no coming back. That is because many people had internalized national media views of what to say about any national political issue you came up with.

But if you didn’t start that way, then you could find that on the rest of human and community existence, people could generally be reasonable, positive minded, practical minded, et cetera, et cetera.

And I have two questions. First, is that your experience too? And second, what is your response to a comment that I often got, which is: “Yeah, you say people are reasonable, but they still are voting in these extremely polarized ways. And that is what counts.” How do we reconcile those realities?

Ruby

We don’t live nationally, we live locally. You live where you live in the neighborhood that you live. You don’t live in the idea of the United States.

I understand that there are people out there where their first question in conversation is about how you vote nationally, and that will determine whether or not we even talk anymore. Yes, I understand that that’s what happens.

People here in our community know that that their co -workers, the teachers at the public schools, they know that some of them vote Republican and some of them vote Democrat. It doesn’t stop them from going to have beers together.

Okay, the people on the knob here know that some vote Republican, some vote Democrat, some don’t vote. We live near each other. We send out the group chat when somebody’s dog is running down the road and we pick him up. My neighbors, when we were out a couple of weeks ago, said, “Hey, is it okay if we come walking on your trails?” Absolutely. If you need anything in the house, just go on in. Okay.

When you live locally, it doesn’t matter. Everybody has their civic duty to go vote, or obligation–or you don’t even have to. You have the opportunity to go vote. It doesn’t mean that that takes priority over neighborliness. And I wish that people, especially on the East Coast and probably also equally in the Northwest–you know, the coasts–would realize that living locally forces you to prioritize things that are more important than who you voted for.

Okay, now they might say to you, oh, that’s going to affect all parts of your life. But it really isn’t going to affect all parts of your life. You’re still going to have to go to see the doctor regardless of who’s president, you’re still gonna have to go buy vegetables regardless of who’s president. And the price of gas, the president just has so little to do with the price of gas, right? And so you’re gonna live your lives locally, largely, like my local life has not changed between when Obama was president to Trump to Biden.

Fallows

But there are areas where voting nationally does affect life locally. The 1860 election. It MADE A DIFFERENCE how that came out nationally. And the 1940 election, et cetera.

There are big changes. The national tide ripples down. It mattered that FDR was there, instead of Herbert Hoover in 1932.

So how do you, both in your own life and in your community life, how do you think of recognizing that national decisions actually do matter — yet there is this reality you described that people live locally. How do you reconcile those two realities?

Ruby

Sure. National decisions actually do matter. I don’t think that we would have pickup truck rallies with Confederate flags rolling down the streets if national elections didn’t matter. That is something that people have to deal with. They have to deal with seeing that when they’re out shopping. They have to deal with the distraction that this causes, emotionally as well.

They can’t unsee those things, and then they have to wonder if these people are going to school with their kids. We talk about this with my book club brothers — and you’ve met them too — about how these issues impact the people that you see on the streets and now what you can and can’t talk about.

What I’m saying is that those things are impactful, but I don’t think that you need to make them… You have to take them as part of the equation. They are a variable that’s part of the equation. How much you weight that variable in the equation is going to determine how willing you are to either not deal with those people at all, or to allow it to be an annoyance to you that you can deal with in life.

Is that fair?

Fallows

I think that is reasonable and in accordance with our observations, too.

I’m going to ask you a personal and local question, and then some bigger picture questions. So personally, what’s the biggest surprise you and your wife and your family have had? Something you didn’t expect about living on the knob in Kentucky that you hadn’t foreseen?

Ruby

I didn’t think that it was going to be as cosmopolitan as it actually is. We live in a red county, but even the red is very purple, if that makes sense. So it’s very interesting to me that if you try to bifurcate something into a one or a zero–a red or a blue–well then you can say yes, we live in a red county. It’s very reassuring to me how purple the county actually is.

So people that vote blue do things that you would consider red, like shooting guns out here. My sister-in-law), the first time she came from California on a Saturday morning, she says, what is that noise? And I said, people are out shooting. And she says, at what? And I said, I don’t know, targets, I guess. Why? Because they live in the county and they can. Are they hunting? No, they’re just out shooting. But they came and moved out here and bought property out here and they’re moving here.

And so it’s very interesting that even people that vote blue like to come out and shoot guns and they even come out and hunt with us. The people that consider themselves red, they like to go to the brew pub, they like to go to the Centre College Performing Arts Center to see the shows that come through. It’s very purple.

Fallows

That is really interesting. I’m going to insert a little factoid here. Or, a factlet–because I think a factoid means it’s false, but a factlet is a little fact:

There was a fascinating large database story in the Washington Post a couple of days ago trying to explain what is one of the biggest health disparities between counties that vote red in the US and those that vote blue. And it appears to be hearing loss, which seems to be related to exposure to gunshots. That if you plotted the number of people who in their lives have fired more than a thousand rounds of ammunition, that has a very strong sort of partisan lean these days. And that seems to be a very major factor in premature hearing loss.

Ruby

So I’d add something else. I’d add something else to that. And that’s equipment.

In the city, you don’t need a zero-turn mower or a tractor. But everybody out here has one. And everybody is exposed to that. So I’m exposed to the noise of the chainsaw more than people in the city are, we heat our house with wood that I cut up myself. Yes, we have a furnace, but we heat our house primarily with the wood stove in the wintertime. Most of our neighbors do.

So the sound of chainsaws is prevalent around here. The sound of tractors is prevalent around here. Liberals and conservatives have tractors and chainsaws and zero turn mowers. And so I think that that might be a factor In premature hearing loss, add to it in addition to gunshots.

Fallows

Yes, that rings true to me. And I won’t even get to the urban and suburban phenomenon of gas -powered leaf blowers, which we’ve discussed before.

Ruby

So that we don’t have, yes, that’s true. So that is the noise that you hear in the suburbs. We don’t have leaf blowers out here. Nobody out here has leaf blowers. You know why? Because nobody around here cares if you have leaves in your yard because nobody here has lawns.

Fallows

So let me switch to big picture themes that you’ve written about a lot and you’ve spoken about.

In your career as an Air Force intelligence officer, you’ve studied the ways that civilizations either coexist, or come to conflict. And you’ve written for the Our Towns site, and other places, about ways in which governments and populations can cohere or not, or the ways that they come apart.

Two years ago, you wrote a very interesting piece for our site, just examining the evidence that the US might be coming to a breaking point. As you know, my own theory is the US is in trouble and always has been. And that’s sort of the saga of the US of trying to deal with these eternal strains.

But you’re talking about a national level polarization that seems, if anything, to be getting worse. What is your current view? About how the US both will and should manage the coexistence of this local level fabric and the national level fraying and tension of the fabric?

Ruby

I really like your analogy that we’re always just, please correct me if I’m misstating it, but you seem to say over the years that we’re always just treading water, that we’re not quite drowning, but we’re never going to be able to make it to shore. It seems to me that the biggest that could tip us is that we are self-sorting. Okay, we have self -sorted into very, very liberal neighborhoods and very, very conservative neighborhoods.

And even when you see what’s happening in migration to Texas, that’s almost entirely blue migration, and that’s almost entirely into already blue cities. And so while Texas may still be red, it may end up going to blue, okay, because of Houston and Austin, and parts of the [Dallas-Fort Worth] Metroplex, not the entire Metroplex.

When you see what’s happening in Montana, Montana is going, it’s undeniably trending towards, it’s becoming purple from red and trending towards blue in the urban areas where people are moving in from the West Coast. The once almost pure-red Idaho is becoming purple largely thanks to a few places that could never have been considered even possible 20 years ago.

And so the self-sorting by wealth is something that’s driving away the kind of localism that we see here on the knob, that we see here in Kentucky.

And I think that if we fray, it’s going to be because of that. If we fray. So you mentioned very astutely that we’ve never had a national election in which the losing presidential candidate didn’t get 40 % of the vote.

Fallows

Yes. And so and it’s in the ballpark of 40 percent. That’s how much even the losing candidate has always received. Herbert Hoover was just under that, Barry Goodwater just under that. But that’s sort of the base.

Ruby

Right, but 60/40 is a pretty good win, okay? And what’s happening now is we’re barely, we’re not even getting to 50-50, right? And, or if we are, it’s just barely 50. And so you may have a large electoral win, but that belies a, let’s say, a more likely split of 40, 40, 20 in the country. People will accept a 55/45 landslide, right? But they won’t accept a 49 / 44 landslide.

They won’t accept that. Now, in actuality, they have to accept that because the person that gets sworn in is the president and gets to sign bills and appoint heads of the departments. But the people don’t necessarily accept that.

Fallows Just to interrupt there, the reality is that the past two Republican presidents have taken office having lost the national vote. It’s not just a win by 49/44. It’s more like 49 / 51, with the 51 side losing.

Ruby

Yes, Bush lost the national vote, and Hilary Clinton lost while Trump lost the national vote. And then the second time around, Bush won the national vote. People are having a difficult time accepting that.

Um, so I think that information availability has led us to sorting. And that sorting has, has allowed for people to say, “Oh my gosh, this is terrible.” In centuries past, you had to live with who you had to live with in the village. Everybody knew who didn’t go to church. Everybody knew who went to church and didn’t really believe. But you had to deal with those people, right? If the miller was a jack wagon [sic], you had to deal with him unless you wanted to start a different mill. If the [black]smith was a jack wagon, well, you had to deal with the smith being a jack wagon or else you wouldn’t be able to have your stuff repaired.

Well, today, people don’t have to do that. They have the ability to move wherever they want to move, and live near whoever they want to live near. And I think that that creates a false sense of security among people..

But what that means on a political level is that we’re never going to get anywhere above at best 50 -50.

And the implications for that are that nobody’s ever going to feel like anything other than that they’re just barely staying afloat. Okay, it’s just going to exacerbate your observation that we’re always in perpetual uncertainty .

There are almost no districts that are not solid red or solid blue. That means that the House might flip, but it’s just going to barely flip. And the Senate is going to be where you’re going to see the big changes. And what that’s going to mean is people can feel comfortable in their little conservative enclave or their little liberal enclave, whatever that means to them to feel safe in their little enclave, however they define feeling safe.

But at the national level, they’re always going to have something to complain about, always. If you live in the cities, that’s where it’s going to be. And because the populations are moving to the metropoles, that is going to be how people live in the future. And that is why I am not confident about the future.

Fallows

As you know, one of my other theories about American life is that every argument we’re having, we’ve had before. There are core arguments that go on forever. And there has always been this kind of sorting.

For example, my wife, Deb, whom you’ve met, all of her grandparents were immigrants from what became Czechoslovakia. And all the Czech immigrants at that time settled in either Chicago or certain places in Nebraska or certain places in Iowa or Minnesota. There just were Czech communities. And the Scots-Irish settled in certain places. And there has always been a kind of sorting of people within the U.S. in communities of people like them. Sometimes this was enforced by redlining. Sometimes It was just by choice.

How is the kind of selection you’re describing different from what has always been part of Irish neighborhoods or Slovakian neighborhoods or Mexican neighborhoods in the U.S

Ruby

The difference is that ethnic sorting is different than political sorting. Okay, the ethnic sorting was for survival and support, mutual support. Political sorting is about ideology.

So, take my Serbian grandparents: My grandfathers came here after World War II, when they couldn’t go back to Yugoslavia because they were enemies of the state because Tito took over and our family were royalists. So when they got let out, when they were liberated from a POW camp by the British forces, they couldn’t go back. So after a couple of years, they made their way over to the States. They settled at first in a Serbian community in Chicago and then a Serbian community in Los Angeles.

When my mother escaped with me in ‘66 and we came over here, we settled into a support network where,, you know, the Serbian church that helped us. Those support mechanisms still exist today for immigrants. But the sorting that we’re talking about is political sorting, ideological sorting.

I think that that’s very, very different because it is based upon ideas, but not providing actual help. The people that sort themselves into these neighborhoods, this is my personal opinion, it is a false sense of security. It is an ideological sorting that these people still don’t know who their neighbors are.

They’re still not going to borrow basil from their next door neighbors or a can of whatever they need, but they do feel better for whatever ideological reason that they’re living next to like-minded people. They’re not in any way the same as people that self-selected into neighborhoods based upon ethnicity for support as immigrants.

Fallows

I accept the point. Another question: If people in New York or in Seattle or in Wausau, Wisconsin or in West Texas or wherever accept your analysis, what then should they do? I’m thinking of the old, the pragmatic philosophers judging ideas by the “therefore, what?” quotient. So if we accept what you’re saying… therefore what?

Ruby

I think the anomie is going to just increase. Okay? People are moving to the metropoles for something that they’re desperately seeking, but can never fulfill them. Okay? They’re desperately seeking some validation, something to spend their money on. Ie you make more money there and you have more things there that can make you happy.

If we look at what the actual evidence shows, people aren’t really happy, are they? People seem to be very unhappy. People say that the politics make them very, very unhappy. They say that living in the city makes them very unhappy, but the city is where they can do the things that they want to do, right?…

People are not happy and we’re seeing as a result a massive, massive, fertility drop. We have these people that identify themselves as de-growthers, saying we have to rapidly de-grow or else we’re going to ruin the planet. If they’re not looking at the actual numbers, they’re fooling themselves at thinking that anything that they can put into place is going to happen before the population collapse actually comes.

Fallows

On the population collapse: That certainly is the story of China now and of Russia and of Europe as a whole and North America as a whole. But Africa in general and India are both exceptions to this trend, aren’t they? And significant ones. So world population is likely still to go up for a while.

Ruby

No, I think actually it’s not actually going to go up for a while because if you look at where African countries are now and where that projected trend is, and Africa is actually topping out on their curve.

Let’s say, I think Nigeria is set to become the third most populous country in the world, sometime in the next couple of decades to overtake the United States. And it’s a fraction of the size of the United States, but their fertility rates are dropping precipitously there. This is happening.

So because there are countries in Africa that still have very high fertility rates, does not reverse the top of the bubble that you’re seeing in Africa and India. Yes, India overtook China as the most populous country in the world, but India’s fertility rates are also really, really precipitously dropping. And without a one child policy, okay, they’re precipitously dropping because of increased economic activity.

So as people become wealthier, as people become, as abundance grows, people stop having kids. And this is what we’re seeing in the world. And so that’s actually going to exacerbate, exacerbate these divisions.

Fallows

So let me ask you one other question as a link to a further discussion I hope we can have. I know that a lot of your intellectual and personal energy goes into the works and activities of the Chesterton Society. And could you just give a teaser of why you view GK Chesterton as a very important intellectual and moral figure for this moment in our lives.

Ruby

Chesterton was a man of his time, but he was a man that spoke timeless truths.

I have I have some very, very liberal friends on Twitter and some very conservative friends on Twitter. And when they all read him for the first time, they say, holy heck, he’s talking to me today. He was speaking to me as if he wrote me a private letter.

A friend of mine in Atlanta that started a new business has done so largely because he read several books of Chesterton’s, particularly Chesterton’s biography of Francis of Assisi. And it spoke to him so personally that, he decided to change his entire life both spiritually, religiously, personally in his family, and then economically, all four of those, spiritually, religiously, personally and economically, he changed his life.

That’s an incredible testament to somebody who died in the 1930s, who when he came to the United States, sold out theaters across the country. He sold out Madison Square Garden to speak. He was a speaker for a semester at Notre Dame and filled the convocation hall every time he spoke.

Chesterton said, in What’s Wrong with the World–I have a little first edition copy here–he talked about people always looking “forward.”

“The upshot of this modern attitude is really this, that men invent new ideals because they dare not attempt to look at old ideals.

“They look forward with enthusiasm because they’re afraid to look back. Among the many things that leave me doubtful about the modern habit of fixing eyes on the future, none is stronger than this, that all the men in history who have really done anything with the future have had their eyes fixed upon the past. I need not mention the Renaissance. The very word proves my case.

“The originality of Michelangelo and Shakespeare began with the digging up of old vases and manuscripts.”

And so when he tells us that, you know, if we really, really want to see greatness in the world, we should look at not just forward what people are building in big cities, but not to forget that big cities were built by hand before we had computers , that Cologne Cathedral took 800 years, sorry, 600 years to build. Imagine starting on something that your great grandchildren won’t even finish. And so I think that Chesterton talks to us today with clarity. There wasn’t a single topic that he didn’t talk about then that you can’t find today something to help us, you know, focus our minds on.

Fallows: Tom Ruby, thank you, we have more to discuss.