None of us planned it this way, but my wife Deb and I happened to be reporting from Mississippi at just the time when when Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “Case for Reparations” article, which starts with scenes from Mississippi, was coming to such deserved attention.

What Deb and I have been discussing is loosely parallel to, rather than directly engaged with, the issues of legally enforced racial injustice that are central to Ta-Nehisi’s story and its follow-ups. We have been looking at the ways a part of the country with this heritage—on average quite poor, historically under-industrialized, with about three times as great an African-American population share as the country as a whole (about 38 percent in Mississippi, vs. about 13 percent for the United States) and with a history of racially based mistreatment of its black population—moves ahead now, as every part of the country aspires to do. We’ve had Ta-Nehisi’s articles in mind as we’ve been writing, and I think the accounts of Mississippi then and Mississippi now can usefully be read together.

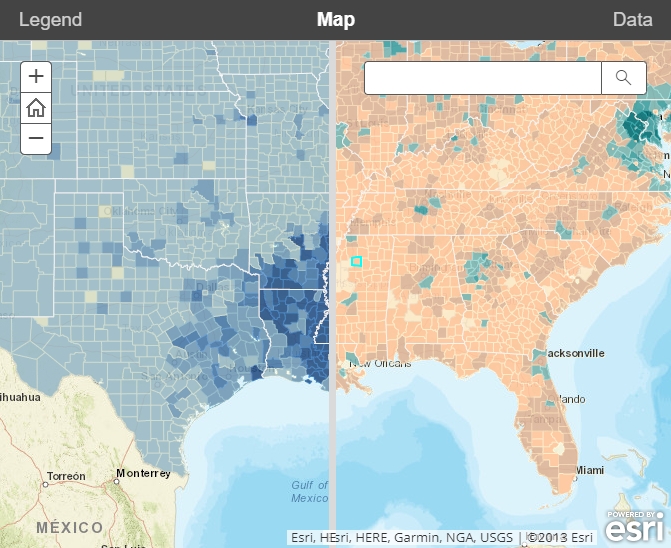

As a reminder, here’s a “swipe map” by John Tierney, matching proportions of black population across the country with median household income. (Click “Hide Intro” to see more of the map. You can zoom in and out and pan to different parts of the country. Also you can follow a link to a more fully featured, but non-embeddable, version of the map.)

In the latest installment, I quoted a reader from the North arguing that on balance it would have been better for America if Mississippi stayed poor. The reasoning was that industries coming into lower-wage, emphatically non-labor-union Southern states were part of a “race to the bottom” that has immiserated the middle- and working-class everywhere. That reader and others faulted me for not laying out my own views on the race-to-the-bottom question as regards Mississippi, whether or not I’d done so in previous books or in reports from China (which is of course as the center of “race to the bottom” patterns worldwide).

I’ll do that, but as part three of today’s three-part plan. Part 1 is factual clarification from Joe Max Higgins of Columbus, Mississippi, who has been at the center of some recent reports. Part 2 is a selection of messages from readers on the “race to the bottom” / “let those Southerners stay poor” theme. And part 3, after the jump, is my summary view.

***

Part 1: Joe Max Higgins and the new industrial wage. Earlier I mentioned that Joe Max Higgins, of the business-promoting “Golden Triangle LINK” organization in Columbus, Mississippi, had one big guideline for the industries he hoped to attract. Namely, that they pay a lot more than people in the area already earned.

As a benchmark: the median household income in the United States is just over $50,000 per year. In many parts of Mississippi, it’s barely half as much. Then when the enormous, high-tech Severstal steel mill opened up outside Columbus, employing hundreds of people at an average pay (before benefits) of $80,000, Higgins said that he regarded this as a huge win for his area. A reminder of what it’s like inside the mill, from a company video that exactly resembles what I saw:

Many people wrote back to say: Eighty thousand dollars, on average? No way. You’ve been conned! So I went back to Higgins. He showed me evidence of a formal agreement between the mill and the State of Mississippi that the average pre-benefit pay must be at least $70,000. And at the latest audit, it was just under $80,000.

I’m not getting into the possible differences between median and average earnings there, or what the workers give up or gain by being in a non-union plant. I’m saying that there’s a reason the mill had so many thousands of applicants when it opened up, which is that its jobs are such a step up for local workers. (And, before you ask, there is still an installment coming on how local people are being trained for these jobs.)

***

Part 2: Let’s hear from the readers. There has been a very large volume of mail, from which I am trying to take representative samples. Here goes.

• Think of the TVA as reparations. A previous reader objected to the TVA even trying to speed development in Mississippi: “To be honest my chief reaction was to wish that TVA funding was quickly and permanently yanked. I do not support federal funds in order to develop this political cesspool into an influential center of the American economy.” Another reader, originally from Wisconsin, responds:

I moved to the mid South about 12 years ago, and very few days go by when I don’t find it alienating still. However, your piece on the Black Belt in Mississippi caught me up.

To reference TNC’s recent Atlantic article, a TVA designation of “Megasite” plus Federal/State/Local tax incentives could be argued as the sort of economic policies that target the development of poor communities, and if focused on areas historically affected by racist intent/policies (e.g., chattel slavery in the Black Belt of the South followed by sharecropping, lynching, disenfranchisement, Jim Crow, etc., etc., etc.), a sort of reparation. (Did that sentence contain enough hedges?!)

Although I too decry the political shift I feel in the nation as a whole which I think is in large part driven by the weird Republican values emanating from the South, I believe policies of infrastructural development such as the TVA “Megasite” are essential for moving forward. My electricity comes from TVA and in general I do not herald their track record (e.g., Kingston Fossil Plant in Harriman TN). However, I was heartened to read about the “Megasite” policy. TVA is not perfect but as a hybrid Federal/State/Private entity, maybe it can be steered toward more progressive ends (could not for the life of me find a better word than progressive there…)

An aside: a pox on those in my home state [Wisconsin] who have lost the true “conservative” Republican values of my father’s family who fought for the Union.

• Also about the TVA. A reader, who discloses that his firm does business with the TVA, adds this note:

A minor nitpick with your reader who dislikes the TVA megasites due to it being federal funds helping a region of the country she dislikes politically.

The TVA does not receive federal funding, it is a self funded agency, funded through ratepayers and bonds.

• “They may be charming, but their policies are killing us.” In support of the original “let Mississippi stay poor” message:

Add me in as another regular reader who has a hard time much caring about economic gains in white Mississippi. [JF note: the regions I’ve been writing about have been majority black, and the factory work forces are integrated.]

As a young person, I was too much of a snob to work at learning this history of my own country — much snazzier to concentrate on Europe and Africa — so I’m doing some catching up as a semi-retired adult. One of the insights I’ve gotten through working my way through the Oxford History of the United States is that the shape of modern US society was set by the absence of representatives of the Confederate States from Congress in 1860-65. I don’t just mean emancipation, though that’s the root. I mean the Homestead Act, the Land-Grant colleges, “internal improvements”, a modern-ish federal government and direct taxation system. With the Southern obstructionists around, we could not have had any of that.

And the southern states, insofar as they are controlled by whites (almost entirely) don’t seem to have changed much: they exist to impede all forms of necessary national public policy: access to health care for all, education, reasonable gun control, etc. In this era, climate crisis is the moral equivalent of the emancipation struggle and these states, along with some western types who imagine themselves solitary cowboys, would rather all our descendants suffer than sacrifice their phony extractive culture.

The only reason I can imagine attending to the economic struggles of the South is that the majority of this country’s Black citizens live there. It would be an additional white crime to abandon them to the unhindered depredations of their white neighbors.

What to do I don’t know, but you lose me when you are celebrating industrial development using non-union labor that props up a state whose representatives throw themselves against everything that makes this country and the world work. I’m sure they are charming, but their politics are killing us.

• “Do these people think we can’t read?” A note on anti-Southern attitudes:

These comments show explicitly an attitude that has been pretty common from the beginning of the civil rights era- hatred and contempt by progressives for those they consider not sufficiently with the program, most obviously southerners but also non-elite, non-progressives whites outside of the south.

Do these people think we can’t read? Or are too stupid to understand what their real feelings, intents and motivations are?

• “The real question is, what’s the worst we will put up with?” Mike Levsen, the mayor of Aberdeen, South Dakota (whose city we have coincidentally planned to visit), writes:

We will always try to steal other cities’ assets when the opportunity is offered (and have done it); it is expected of us as city officials. So, I don’t question the Mississippi people, even if it correspondingly causes distress elsewhere. Interestingly, nobody ever suggests we are destroying the work ethic of those companies by giving financial help, the way it is assumed by many that social welfare breeds laziness.

To me, a more essential question demanding answer is “What will we put up with”, not where.

There will always be people occupying the bottom one-fifth or one-tenth.

We spend much time discussing who, what, where, why…but I don’t care about those questions.

Whether by race, geography, legacy, age, or any other demographic indicator.

Whether or not they are responsible for their own situation or undeserving in any way.

Whether they are able to exit from that status or not

They are among us.

Those exiting will be replaced by others who will be a part of our life, our country, our future, and occupy that bottom cohort.

The question is, what is the worst state of life for that bottom rung that we will put up with. How bad does the housing, nutrition, healthcare, educational opportunities, family services, environmental protection legal system access, and all the other things that are degraded by a lack of money have to be before we say it can’t continue. …what’s the worst the rest of the country will put up with…

It’s not important where they are, what’s necessary to acknowledge is that they exist in that situation, and everyone else is also the worse for it.

• “Strategically brilliant but morally bankrupt.” From a reader in a big East Coast city:

As a Citizen of this great country, someone who has more than a passing acquaintance with American history in regard to industrialization and things north/south and also someone who builds all over the United States and Canada, I continue to wish that we could somehow meet in the middle on the work issue, because there truly are two legitimate sides to this story.

The actions of various Southern state governments and their business partners actions have been strategically brilliant but morally bankrupt. To wit, South Carolina. They receive $1.92 in Federal funding for every dollar paid, gleefully using the differential as a subsidy for their low wages, low property taxes and poor services, all while issuing a steady stream of anti-Federal, pro-State rhetoric.

States like South Carolina are all about the business owner and only about the worker in the most basic sense that they see them as units of production, nothing more. From a development perspective the best monetary example of how South Carolina would act if they were allowed is by building the Burj Khalifa, which cost $1.5B for 5M sf, or $300 psf.

On the other side, we have the legacy airline and automobile manufacturing unions, who have continued to make their own collective beds through continuing to demand luxurious pensions, European-style working hours, confiscatory base wage, overtime and double time rules, and refusal to modernize their approach towards work and a continued erosion of quality of work that used to separate them from non-union workers. The best development example of how this still works in the US is the Freedom Tower, which cost $3.8B for 3.8M sf, or $1,000 psf, or 3.3 times the cost of the Burj Khalifa.

I’m equally frustrated with both sides. People in work for Boeing in South Carolina need to make more. People who work for Boeing in Washington need to make less. Benefits need to generally equalize on both side.

• And what if Lincoln had lived? To wind up this part for now:

As a native of the upper south (Kentucky) and a student of history generally, I consider myself “southern” in a general kind of way. I have two graduate level degrees, and am currently living in the Mid-West. My speech, however, is peppered with the southern and country idioms, and while in informal company, I am still apt to drop the g’s of words ending in “-ing.”

My political beliefs are left and Democratic, despite the conservative nature of the Kentucky Democratic Party: I can point to real things in my family’s more humble beginnings that are the products of the hard work of my forebears, certainly, but which were made available TO my forebears during hard times by Democratic administrations. THAT is the Democratic Party in which I believe and for which I still vote unflinchingly…

Your post yesterday regarding the affirmative answer given by an urban resident of a Rust Belt city to your hypothetical question, “Should Mississippi remain poor?” prompted a reaction in me, as I’m sure it did (and will) with many others, perhaps none more so than residents of Mississippi. My own reaction, however, is more of an “Amen!” of sorts rather than a typical “circle the wagons” response from a fellow southerner.

I have taken enough history courses to know understand how the anti-union and union-busting policies of the South in general have led to a “national race to the bottom” as your correspondent pointed out, with Northern industries decamping to states where unionization is at best discouraged, but where the State actively pursues policies favorable to “business growth” – low taxes, right-to-work laws, lax environmental regulations, and so on. The move of the textile industries from New England to the lowlands of the Carolinas and Georgia after the Civil War is just such an example.

I am also aware that as much as the South has been guilty of economic depredations against its Northern kin, it has also been a victim. After the Civil War, the untapped natural resources of the South were snapped up at bargain prices by Northern interests, whether it be West Virginia’s and Kentucky’s coal, Georgia’s timber, Alabama’s iron, etc. These new industries were, of course, abetted by the aforementioned state policies that gave them, more or less, a free hand to do as they pleased, whether to the resources they controlled and processed, the workers they employed, or the land they despoiled.

As an American citizen (not one of Kentucky or ‘the South’ alone) with progressive political beliefs, I can understand your correspondent’s dark suggestion that perhaps, yes, Mississippi should be left poor. If increasing economic clout means “the Mississippi model” works, and therefore, her policies should be emulated elsewhere, then I might tend to agree with her. I’ve watched President Obama try to solve some of the nation’s toughest problems with both hands tied around his back by an intransigent opposition that has sometimes appeared willing to destroy the nation in its zeal to “save it” from Obama’s policies. Examples of this, and other, clearly race-based policies, such as those that have rolled back voting protections in the South, etc., have just left me disgusted.

I don’t know how you feel about “alternate history,” but I’ll go one better than the Rust Belt correspondent. I very often wonder how different (and presumably BETTER) the nation as a whole would have been had Lincoln lived, and, instead of his passive “prodigal son” reconciliation with the South, he had been inflamed with a real sense of remaking (with a “Radical” Republican Congress) the South for all times:

– the entire political and military leadership of each seceding state being seized and forcibly removed, either to the North or West, or otherwise given the opportunity to be banished abroad, but removed from the South at the least;

– the political and economic vacuum in the South filled with the growing ranks of the Northern urban poor and immigrants from abroad;

– massive agricultural and land reform;

– investments in infrastructure projects and education; and

– perhaps even a redrawing of jurisdictional boundaries, such as redrawing state boundaries, creating new states with new names, etc….Such a thing as this “remaking of the South” is unimaginable in American society or history, and thankfully (for the South, perhaps, at least) we had a man with Lincoln’s temperament instead of, say, Stalin’s at that time and in that office. From the nation’s fraught history with race, and with that region’s desire to seemingly stymie nearly every effort to advance public policy that brings light to the darkness and knowledge to the unlearned, it would seem, sometimes, to be a price worth paying.

So here is a bullet-point summary of arguments I’ve made mainly in books More Like Us, Looking at the Sun, Breaking the News, Postcards from Tomorrow Square, and China Airborne, and a number of Atlantic (and New York Review of Books and Industry Standard articles) since the 1980s.

• I view economic success as a matter of adjusting to an endless series of changes—technological, environmental, cultural, business-competitive, geostrategic, you name it—as quickly and smoothly as possible. The changes will never stop. Individuals, companies, regions, and countries do relatively better or worse depending on the ease and speed with which they adapt.

• Beyond their skill in adjusting, individuals, companies, regions, and countries can sometimes bend the direction of change in their favor, to increase their absolute and relative success. Regions or countries can often do this by investing in infrastructure, research and development, and education.

• Through the past two centuries the United States has overall fared very well thanks in part to success in both these areas. Its culture, laws, policies, geographic openness, and ideas about itself have generally encouraged adaptability. And its policies have bent change in its favor—through expansion of mass education and a research established, through public investment in leading technologies, through remaining attractive as a site for immigration, et cetera. All this is on top of the incredible natural advantages the U.S. enjoys because of scale, resources, distance from enemies, etc.

• The successful American bargain has depended on relative mobility, openness, and egalitarianism, with the obvious enormous exception of slavery and its aftermath, and many other lesser barriers. As legal changes make America even more equal and mobile, it should become more successful in the basic job of adaptation. As economic and other shifts make it more unequal and class-bound, it becomes less itself, and less successful. (This is the whole point of More Like Us.)

To put this in recent historical terms, from the 1930s through the 1970s, most national and regional policies in the U.S. increased its adaptive mobility. Infrastructure building, the expansion of elementary and higher education, social insurance programs, public investment in high tech. From the 1980s through now, the net effect has often been the reverse.

• Trade policy can also be an important part of the mix. The U.S. had an infant-industry protective approach through most of its 19th century rise. A generation ago, it needed to rebuff Japan’s mercantilist policies, and it largely did. (Eg through Sematech.) These days it has major rule-of-law, cyber-theft, and intellectual property disputes with China.

• In this process there are such things as “tragedy of the commons,” and “race to the bottom.” Tragedy of the commons is the linked disasters of the worldwide environment, from the depletion of the oceans to the failure to deal with climate issues.

“Race to the bottom” is competition of a particular type. It’s not the shift of industries to ever-lower-cost sites: Old England to New England, New England to the South, the South to Mexico, Mexico to coastal China, coastal China to inland China, all of China to Vietnam, Vietnam to Bangladesh—and now backin many cases. That is the nature of centuries of world capitalism, and from a worldwide perspective it’s been an important agent of equality. “Race to the bottom” is a self-defeating, self-enhancing cycle of competition that ultimately leaves everyone worse off: ever-laxer environmental standards, in the most obvious case. China is realizing, very late, that it has suffered through race-to-the-bottom environmental standards, overwhelmingly by its own rather than foreign firms.

• There are also such things as unfair competition, abusive concentrations of power, preying on the weak, and all the other reasons that from Adam Smith to Teddy Roosevelt onward, real capitalists have embraced regulation.

• To concentrate on the business rise of the American South, I disagree in two ways with those who see Mississippi’s industrial rise as reflecting America’s “race to the bottom” economic decay. (Even apart from the fact that people in Mississippi are, how do I put this, Americans too.) First, there is little to no evidence that Nissan, Toyota, Severstal, PACCAR, Airbus-Eurocopter, Yokohama Tire, or other big recent entrants are there because they have been given the OK to be extra dirty and pollute. They haven’t.

Second, their presence in Mississippi or Alabama is not the reason for industrial hard times in what we now call the American rust-belt. Elaborating that point is the stuff of many books. For now I’ll leave it with this: wages in Mississippi are lower than those in either Japan and Germany, and Japanese and German firms are opening factories there. But that isn’t making them “race to the bottom.” They are not hollowing themselves out. If that is happening elsewhere in the U.S., it is not Mississippi’s fault.

I realize that in a 10,000 word (or whatever) post I can’t say “In short…” But in short, by my lights the big American problem is the constellation of forces that make us less mobile, less egalitarian, less adaptable, less fair. And in that perspective, the spread of industry and opportunity to an area that has sorely lacked them is progress for America, not the reverse.