If you spend even a day or two in Eastport, Maine, at least one of its proud residents will probably lead you to the water’s edge and point across Passamaquoddy Bay to Campobello Island and the summer home of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. The house has a green roof and a broad lawn sweeping down to the water. It is where FDR was struck down with polio in 1921.

During our most recent visit to Eastport for our American Futures project, we finally got to visit Campobello. We also discovered a few surprising things about how the Roosevelts’ transit through downeast Maine by train and ferry to Campobello affected our American Futures project a good 80 years later.

In 1920, when FDR was waging a failed run as vice-presidential running mate to nominee James Cox, he stopped in Eastport to give a speech. He also endorsed the design of a young engineer who proposed a way to harness the power of the Passamaquoddy Bay tides to generate electricity.

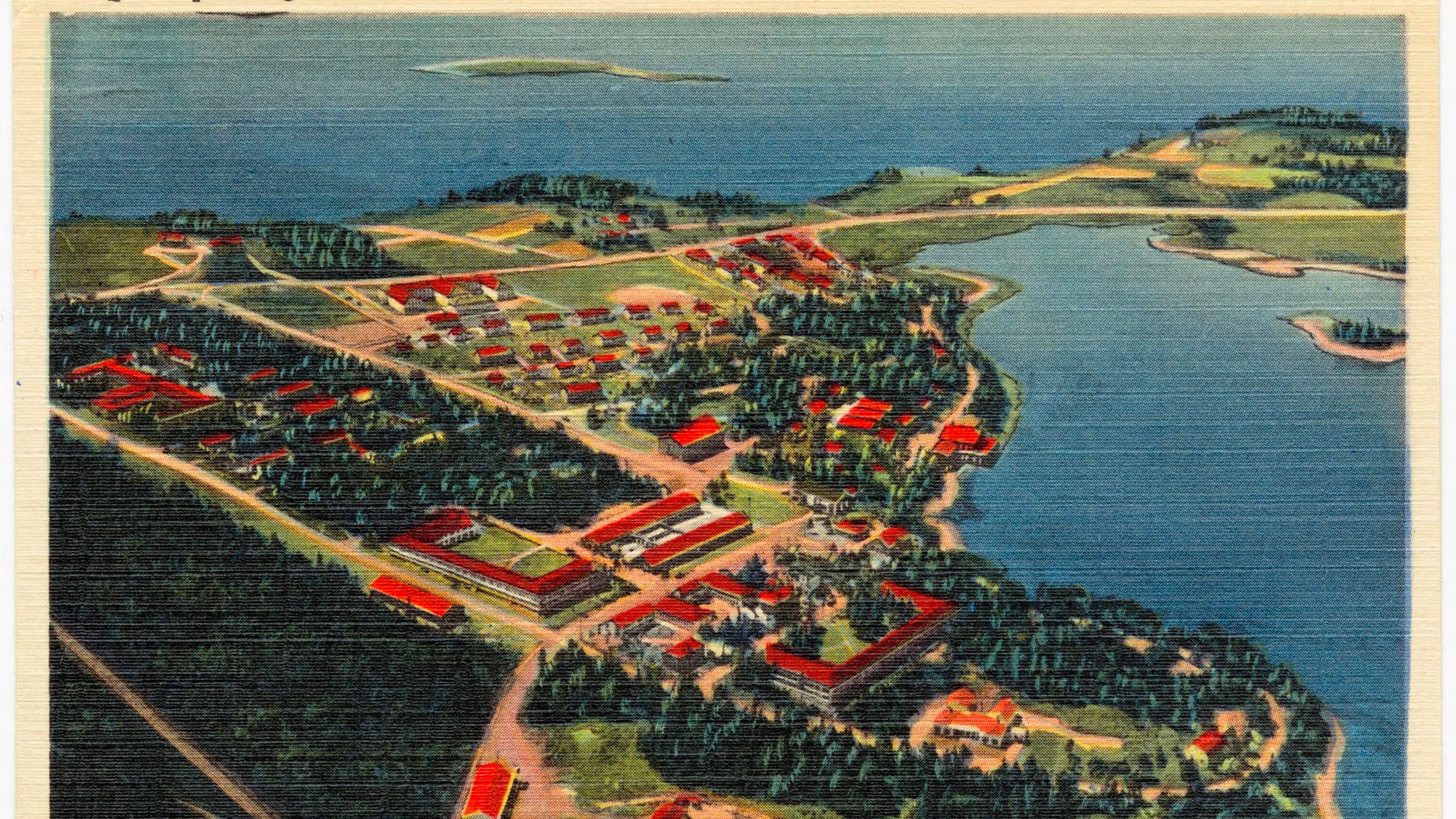

In 1935, the controversial project eventually received seven million dollars from FDR’s administration under Public Works Administration funding. This built two dams, a navigation lock, a gate, a generating station and a small residential area called Quoddy Village for the workers and their families.

All this effort was extremely short-lived; Congress blocked further funding for the project, and work halted in the summer of 1936. Everyone moved out of Quoddy Village. (The idea for harnessing tidal power was a great one, however, and it has returned in promising and now well-funded form. Jim wrote about it here.)

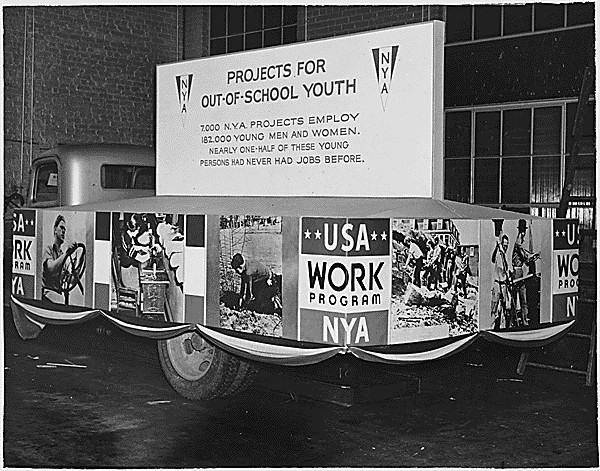

In 1937, Quoddy Village was turned over to the National Youth Administration (NYA), a WPA-model project to provide vocational training and work experience for some of the vast population of underemployed Depression-era youth. The effort in Eastport was called the Quoddy Regional Project and described as “an experiment in youth rehabilitation.”

Over the next seven years, the comprehensive project accepted groups of hundreds of young men in their late teens to mid 20s from needy New England families. For at least five months at a time, the young men were oriented, trained, given work assignments, and evaluated. They brushed up on their English and math skills. The project looked after their medical and dental care and their recreation, including sports, dances, and movies. They had library time, put out a paper called the Quoddy Eagle, took citizenship classes, and elected a mayor and council for their Quoddy Village government. They lived two-to-a-room in two Quoddy Village dorms, which had been built for tidal-project workers. They ate plentiful, healthy food. As noted in a very poignant description in the 1940 report was “an almost immediate gain in weight on the part of the great majority of junior personnel.”

Eleanor Roosevelt, an enthusiastic supporter of the NYA took the ferry from Campobello to visit Quoddy Village in 1941, and wrote this report as one of her regular columns for the Boston American:

We are having the most wonderful weather … Yesterday morning, on the water, it was cool and we had a grand breeze on our way over to Eastport. Once landed there, we took a taxi and went out to Quoddy Village to visit the NYA resident project.

I had not seen this project since it had been turned over to the boys. I was impressed by the excellence of the work shops and by the tremendous interest which the boys show in the work they are doing in aviation mechanics and the regular machine shops. They have good classrooms and have set up an instrument room now, because they found a demand for men who could work on instruments.

The gliders they are making are extraordinarily good, and I hope the Army will send somebody up to inspect them, because I feel they could be used for experimental purposes. an airfield is being built quite nearby, so that some day they will actually see their engines take a plane off the grounds, we hope.

Perhaps the most exciting part of this project is the actual practice of democracy. The law allows no discrimination of race or religion, and these boys have entered into the spirit of real democracy. Since they govern themselves, they see to it that no discrimination exists. They have a mayor, a council and a court. They also hold elections ….

I saw them have dinner. The food is good and yet they do it on 38 cents per boy per day. They plan a full recreational program and seem interested and happy. I think the NYA project at Quoddy is a very valuable project, for it seems to be turning out good men.

I was struck in a back-to-the-future way by one comment Eleanor wrote: We took a taxi and went out to Quoddy Village. There were taxis in Eastport! The first lady took a taxi! Today, the taxis are long gone from Eastport; no Uber there yet either. To get around during our visits, we relied on the goodwill of local residents to give us a ride or lend us a car, which they readily did with small-town generosity.

* * *

The work opportunities for the NYA youth were vast and varied. Interestingly, many of the late-1930s version of skills training are replicated in the many, many programs we have seen across the U.S. in the progressive community colleges and technical training high schools today. Some of the names and certainly the technology have changed.

There was cafeteria work (now called culinary skills); carpentry, drafting and planning, and woodworking (which now includes computer-aided technology); electrical work; garage work (now called automotive training); medical services; sheet metal; and aviation work, including construction and maintenance of airplanes. And much more.

By the late 1930s, the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) had begun building airports around Maine as a national defense move. With Eastport’s Quoddy Village aviation work and its strategic downeast location, it was natural that Eastport would be a candidate for an airport. In 1941, construction began. The first runway, 3,000 feet long and running northeast to southwest, is now 4,000 feet long and where we landed on all our visits to Eastport. The first time we tried to land, we had to abort and circle because a man on his mowing tractor was using the runway and didn’t hear us coming. We finally got his attention. The second east-west runway was never finished, but its vestigial limb remains the off-ramp to airplane parking today.

In early 1943, NYA suddenly lost its funding, Quoddy Village closed up again, and everyone was gone within three weeks. It became home for a while to Navy Seabees.

During our last visit, we drove the mile or two to the outskirts of town to have a look at the Quoddy Village of today. Many of the 123 houses are still standing, and better yet, many have been renovated. We found it surprisingly evocative to walk through the streets, imagining the eras that have come before and passed away. The dorms are vacant. The warehouses are vacant. There is no library anymore. But it feels like another second wind, actually the fourth wind, has arrived.

Selfishly speaking, without FDR and the WPA, without Eleanor and the NYA, there would likely have been no airport built. And we probably wouldn’t have made it to Eastport. At the end of our last visit, we put in our request for an upgrade to the field: There is a weather station, but it is not connected to any transmitting capability. Without weather data, we looked in vain for the (faded) weather sock, and we had to scour the skies for the direction of blowing smoke, or flags, or trees swaying in the wind. So, our one request to Eastport: Please activate the weather station!