There wasn’t space to go into it at the time, but I was a fan of the project then, and have become more so as time has gone on, even as political controversy about it has mounted. Reasons for my initial pro-HSR outlook:

• If you have lived any place where HSR is up and running, you see the difference it can make. China’s high speed rail has its flaws, like crashing. But a relatively quick rail connection between Shanghai and Beijing is miraculous. So too with Xiamen-Shenzhen — or Tokyo-Osaka in Japan, or all the ones in Europe I have heard about but not yet taken.

• If you have lived or worked any place in America with even medium-speed rail service, you see the difference it has made. Amtrak also has its flaws, to put it mildly. But just imagine life along the Bos-Wash corridor without it.

• If you even start to think what already-congested, still-growing California will be like without some alternative to increased reliance on cars and airlines, you get depressed. It’s not just the congestion — at LAX, SFO, 101, and “the 405” and all other freeways of the Southland (where freeway names begin with “the”–and where, for the record, I grew up and still consider myself “from”). It’s the doomed choice between building more roads, thus chewing up more land while ensuring that the new roads clog up soon, and not building more, thus ensuring even worse Beijing-style paralysis.

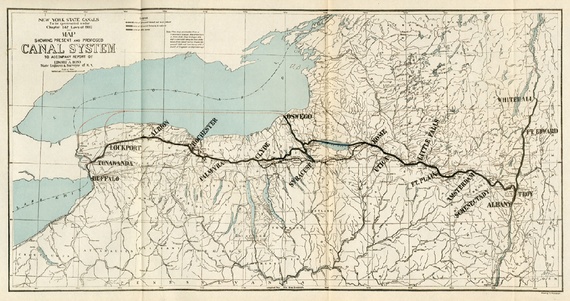

• Plus, infrastructure! Of the right kind. You can think of big transport investments that didn’t pay off, especially if you start by thinking of Robert Moses. You can more easily think of ones that defined countries, eras, economies. For your old-world types, you have the Silk Road or the Via Appia. For the Japanese, the ancient Tōkaidō, or “Eastern Sea Way,” immortalized by Hiroshige, and the modern Shinkansen that covers much the same route. We Americans have the Erie Canal …

… and the “National Road,” the transcontinental railroads, the early U.S. expansion of an air-travel infrastructure, the Interstate Highways, the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate, the international effects of the Panama Canal, plus others. History’s record suggests that big investments of this sort are more often a good than a bad idea. It’s because of the central historic role of transport-infrastructure projects in shaping the growth of states, regions, and whole countries that I’ve made this post part of the American Futures series.

***

That was my pro-HSR starting position. As I’ve read and interviewed over the past year, including on reporting trips to California’s Central Valley, I’ve become more strongly in favor of the plan, and supportive of the Brown Administration’s determination to stick with it. In installments to come I’ll spell out further pros and cons of the effort, and why the pros seem more compelling. For the meantime, here are three analyses worth a serious read:

• An economic impact analysis prepared by the Parsons Brinckerhoff firm for the High-Speed Rail Authority two years ago, which looked into likely effects on regional development, sprawl, commuting times, pollution, and so on.

• An analysis by law school teams from UCLA and Berkeley, which concentrated on the project’s effects in the poorest and most polluted part of the state, the central San Joaquin Valley.

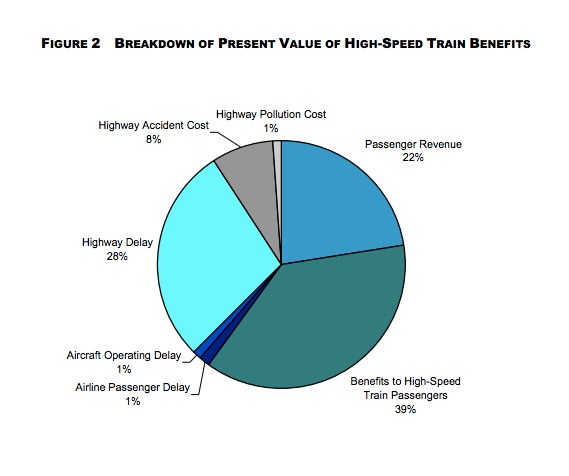

• A benefit-cost analysis by Cambridge Systematics, of the “net present value” of a California high-speed rail system. (NPV is a standard way of comparing long-term costs and benefits.) It had charts like these on the likely longer-term benefits of the project, and said that the costs would be significantly less.

More on those arguments later on. While I’m at it, here is the site of the U.S. pro-HSR association, and here is the one for California’s High-Speed Rail Authority.

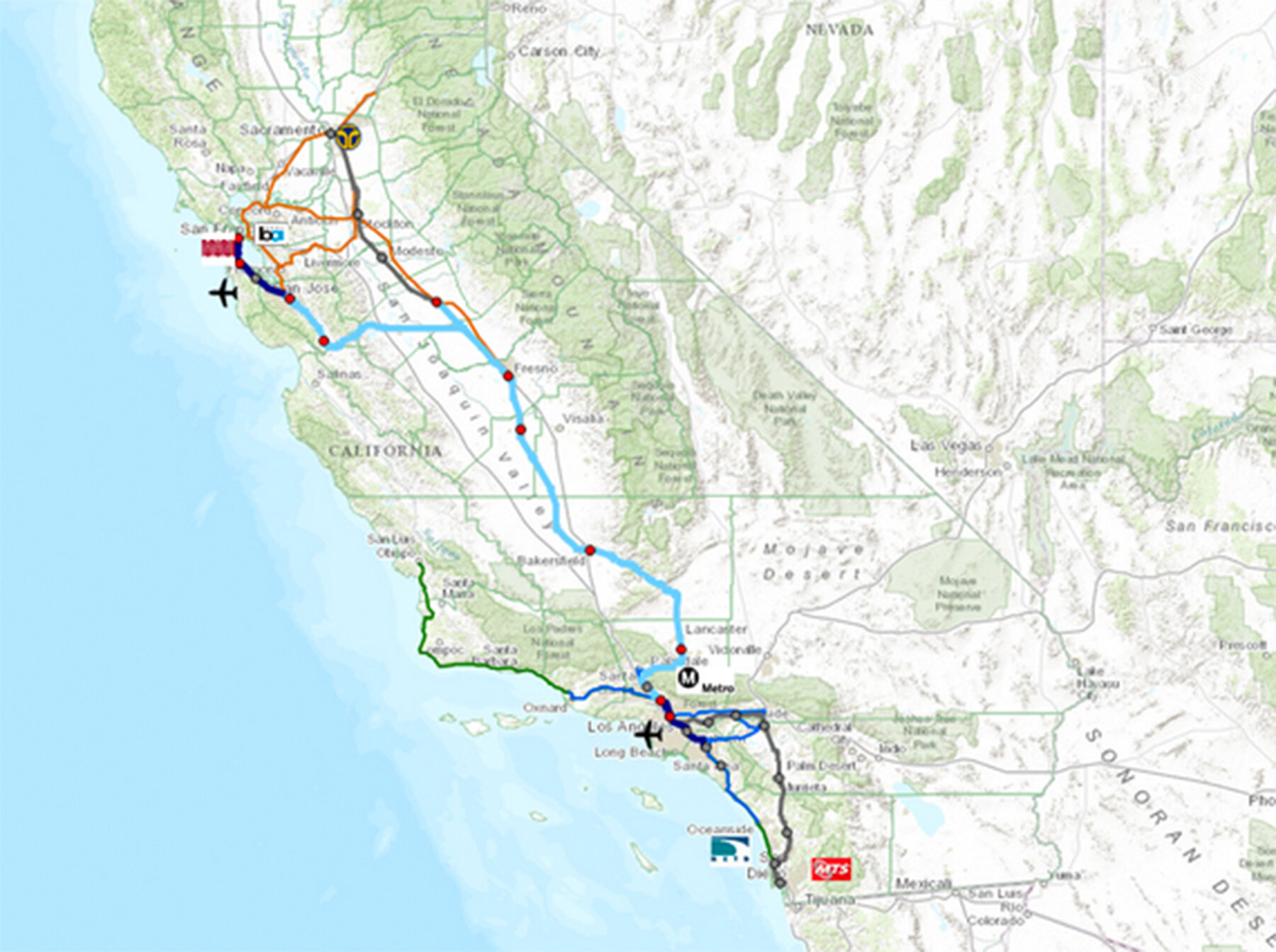

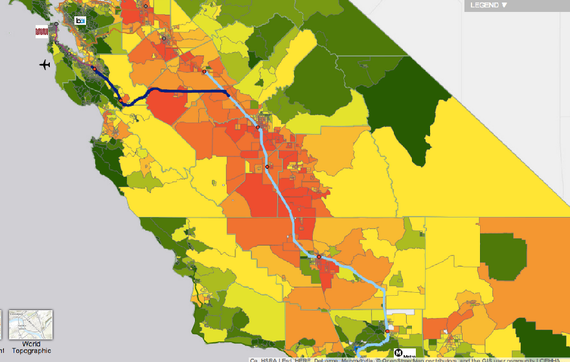

The remaining purpose of this first post is to tee up the topic and introduce a wonderful resource for Californians and other interested outsiders who would like to learn more. It’s a complex and instructive interactive map, based on technology from our old friends at Esri and created by a group of analysts at UC Davis and elsewhere in California. It addresses the most difficult intellectual and political challenge in considering a huge, long-term project like this: namely, assessing or even imagining the long-term, dynamic effects.

***

You can go straight to the maps here, but let me explain a little more about what you’ll find.

Judging the dynamic effect of big projects — downtown restoration efforts, canals or highways or airports — is essential because they all involve “compared with what?” questions. Building a railroad is expensive. But what is its cost, compared with that of building roads, airports, and so on? Building a railroad requires extra land. But how much land will it use, compared with instead building more highways, airports, etc? Trains use fuel and send out emissions. But compared with …

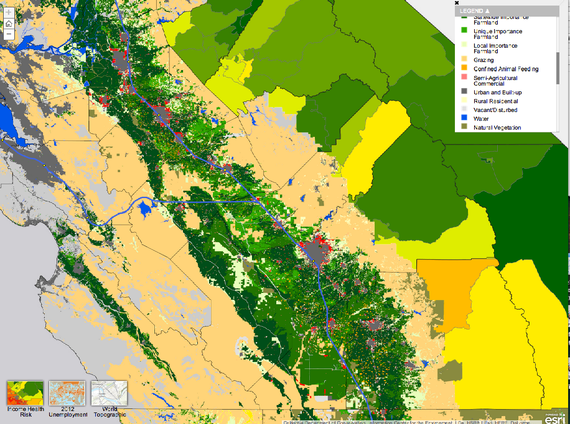

The analyses above all go into these comparative questions. But the interactive maps present the information in a different and more literally dynamic way, by letting you zoom in and out, pan around, and compare building plans for the rail system with the main variables: cost, land-use effects, environmental impact, job creation, and influences on the rich-poor divide that is even more acute in California than in the country as a whole.

For instance, this is a screen shot of the map’s depiction of the system at an early stage of its construction, overlaid on a display of pollution and health stresses in the Central Valley.

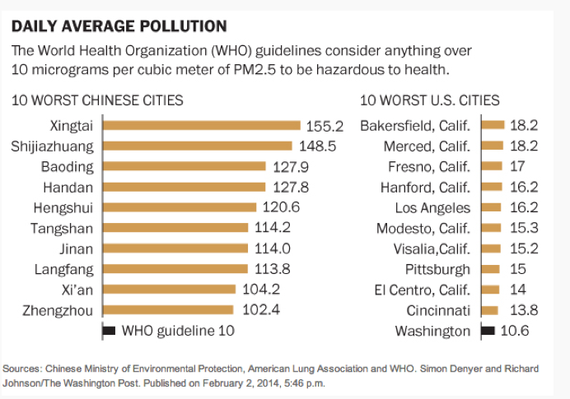

As a reminder of why the environmental situation in the Central Valley is so important, reflect on this chart — previously discussed here, originally from the Washington Post — comparing the ten worst air-pollution cities in China with those in the United States:

The first moral of the chart is: China has a huge problem. The second one is: so does the Central Valley, where six of the seven most-polluted U.S. cities are located, the other being Los Angeles.

There is a lot more in these interactive maps. For instance, here is a screen shot showing the extraordinarily valuable farmland that has already been lost to sprawl around cities from Stockton in the north, through Modesto, Merced, and Fresno, down to Bakersfield in the south. The red dots represent acreage that has been converted to housing developments, malls, and the like. (You can see this much better at the map site.)

A make/break question for the rail project is whether it would accelerate, or retard, the paving-over of some of the world’s most productive farm land. To me, the analyses suggest that HSR would be an important land-saving policy, but go to the studies and the maps to judge for yourself.

That’s it for now. In upcoming installments, interspersed with travel reports, there will be more about the arguments for—and against—this investment. Please prowl around on the maps, check out the studies, and follow on here for the next rounds.

***

For their work on the maps, and for explaining to me what they have put together there, my thanks to: Mike McCoy of the California Strategic Growth Council; Nate Roth of the Information Center for the Environment at UC Davis; Dan Richard and Doug Drozd of the California High-Speed Rail Authority; and Jack Dangermond and many others on his team at Esri.

Update: This post is No. 1 in a series. See also No. 2, No. 3, and No. 4.