Through the 1930s, a woman named Caroline Henderson wrote a popular series of articles for The Atlantic Monthly called “Letters from the Dust Bowl.” She had grown up in Iowa, gone to college at Mount Holyoke, moved to the far western part of the Oklahoma panhandle to begin life as a farmer, and married a man she first met when he worked digging a well on her farm.

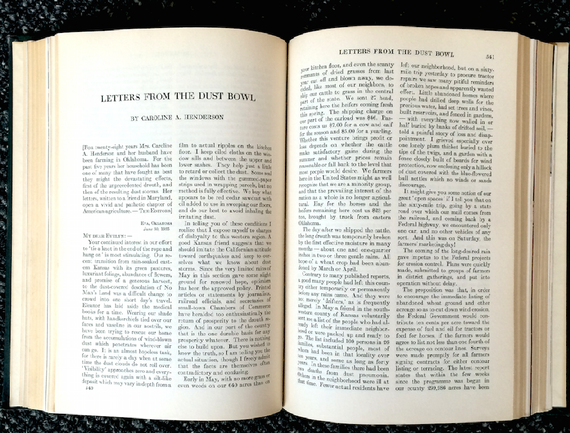

Then things turned very bad for the country, and the high-plains farming region, and the Henderson family and their neighbors, during the combined economic and ecological disaster of the Depression and Dust Bowl years. That is what Caroline Henderson wrote about for the magazine, in installments that looked like this when they were first published (in a photo from our bound volumes, courtesy of my colleagues Jennifer Barnett and Nora Biette-Timmons):

Here is the sort of thing she wrote:

We have had several bad days of wind and dust. On the worst one recently, old sheets stretched over door and window openings, and sprayed with kerosene, quickly became black and helped a little to keep down the irritating dust in our living rooms. Nothing that you see or hear or read will be likely to exaggerate the physical discomfort or material losses due to these storms.

Less emphasis is usually given to the mental effect, the confusion of mind resulting from the overthrow of all plans for improvement or normal farm work, and the difficulty of making other plans, even in a tentative way. To give just one specific example: the paint has been literally scoured from our buildings by the storms of this and previous years; we should by all means try to ‘save the surface’; but who knows when we might safely undertake such a project?…

The prospects for a wheat crop in 1936 still remain extremely doubtful…

You can read some of her installments from the archives here.

Why am I mentioning this? Through this week my wife Deb and I are making our way across the country in our little airplane, getting away from the East Coast just before the big storm on Tuesday night and heading for a period of Western-states reporting for our American Futures series in the weeks to come. Once we get to California we’ll have more to say about some surprising experiences en route in West Virginia and Kentucky.

But I couldn’t let this day end without mentioning the surprisingly emotional effect of seeing the very site from which a correspondent for our own magazine wrote about her and her region’s hardships 80 years ago.

We decided to make the Thanksgiving Day stop in the western panhandle town of Guymon, Oklahoma, a commercial center about 30 miles from the Hendersons’ farm. This is how Guymon looked on the way in today, with a very strong, steady down-the-runway wind that gave a slow-mo feeling on approach, as if landing a helicopter. (“I guess it’s always this windy?” I said to the airport manager after we landed. “What wind?” he replied—but we both knew he was putting me on.)

Then we followed the instructions that Deb had gotten from the Henderson’s grandson, a professor who still owns the land and has observed Caroline Henderson’s wish that it not be farmed. (He now leases it to a man who runs goats there.) We drove west for 20-plus miles, toward the small settlement of Eva. Then up another 2-lane paved road, and then looking for the intersection of two unpaved roads, known as “Road N” and “Road 9.” The GPS lat/long coordinates were a big help.

We found their farm, and the remnants of the buildings whose construction and care Caroline Henderson had described so painstakingly in her dispatches and an eventual book, Letters from the Dust Bowl. With one or two details removed from the frame — modern wires here, a large commercial sow-raising operation in the distant background there — we felt we could have been looking at a scene from the 1930s, minus only the dust.

This part of the country is now connected to the nation and the world in a way hard to imagine when the Hendersons were fighting dust and drought and despair. Yet even now, this area has the distinct sense of being very, very far away from anything, and very much on its own. Here is the view to the south:

And more to the east:

And to the north. In her letters Caroline Henderson describes the barn that Will built. It is now collapsing into itself, the roof timbers falling into its interior.

Everything seemed shaped by the wind, even without its former burden of dust.

In later installments Deb will have more to say about Caroline Henderson’s writings, her life, and her example. At the end of Thanksgiving Day I merely wanted to note the very powerful effect of seeing the very house in which she wrote her chronicles of a terrible stage in the country’s history, the very land that she and her husband and their daughter fought to preserve. (Let alone the improbability of letters she wrote at her desk, which we saw inside the house, making their way to editors in Boston, who made them known across the country.) Most of us fancy ourselves “brave” and “independent” in various ways. But to have even this rough idea of where and how these families lived, through all those years, gives a different meaning to courage and independence. Today I am thankful for what Caroline Henderson and others like her did; and that my wife and I had a chance for this further understanding of the world they lived in; and that our magazine played its part in their saga long ago.

Now, back on the road early tomorrow.