Yesterday PCH International — the company from Shenzhen, in southern China, that is run by my friend Liam Casey and whose exploits the Atlantic has chronicled from 2007 to 2012 — announced yet another acquisition. It’s of the e-commerce site ShopLocket, and the logic of the deal was an extension of what I’ve heard from Casey all along. The main function of his company (and others) has been to shorten the distance — in time, money, effort — between the idea for a new product, and the reality of that product in a customer’s hands.

You can read all about it in the announcement, but here’s the connection to our American Futures journey. ShopLocket is a service for the “maker revolution” — the small startups, all around the U.S. and elsewhere, that are producing new things, and that are using the advantages of today’s distributed commerce to help small, new companies do what only big companies could do before. That is, they can more quickly and easily: get startup capital; refine prototypes for their products; find suppliers and subcontractors; line up distributors and test markets; respond to shifts in demand; and all the rest. This is what Liam Casey was describing to me a little over a year ago, and it’s what you can read about on the ShopLocket site here.

As my wife mentioned before, and as we’re sure to mention many times again, just about everything in the Greenville area reflects the fruits of the “public-private partnerships” that have rebuilt the downtown, attracted international manufacturing firms, created surprising new schools, and in other ways tried to reposition the town as a modern technology/culture/good-life center.

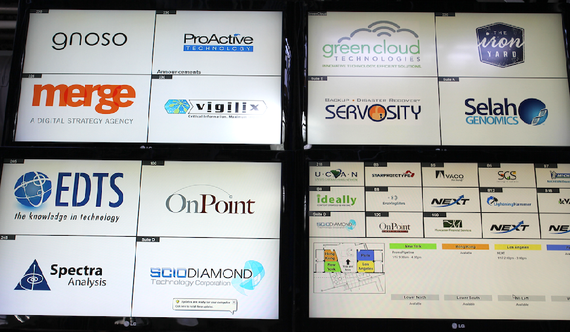

[Before you ask, I’ve received a lot of mail about Greenville’s troubled past in race relations and other barometers of inclusiveness. Greenville County, for instance, was the very last one in South Carolina to observe Martin Luther King’s birthday as a holiday. We talked the past, present, and future of the area’s “openness” with lots of people there and will say more about it in upcoming dispatches.]The Next project is run by the Greenville Chamber of Commerce, with “public-private” guidance from local officials, businesses, developers, and so on. But it is located separately from the main Chamber of Commerce building and is designed to look and feel like a Boston/SF/Shenzhen-style startup center rather than some normal civic building. When we visited there last week, John Moore, a Chamber executive who runs the Next project, told us that it tried to run lean startup-style too. “We had the advantage of starting with a blank sheet of paper,” he said.

“Because there were no existing entities to protect their turf, we were able to leapfrog,” Moore said — much as some developing countries jump entirely past the wired-telephone stage to create nationwide wireless networks. “We went from the idea for the center, to finishing the building and opening it, to having it full, all within three years. If we’d had to start with a university or an existing city facility and tried to change its model, it would have been a lot harder and slower.”

The purpose of Next is to make it easier for new companies to start in the Greenville area. Moore pointed out that this “upstate” region of South Carolina had become famously effective in recruiting big, established firms to set up operations there: GE, BMW, Michelin, and on down a long list. “We’ve been so good an attracting other companies that we may not have done enough to develop our own,” he said. Thus Next and related enterprises — which connect startups with angel investors, provide physical space to get started, offer advice from mentors and startup veterans, and generally supply the sort of surrounding entrepreneurial information and advantage that can come automatically from being in startup centers from Boston to SF.

Has it made any difference? Can it make any difference, I asked Moore, given the scale and distance handicaps of a smallish place like Greenville?

“They’re now coming without recruiting. It’s become a kind of flywheel. The momentum, the acceleration — it all shows the potential. But of course I’m from the Chamber of Commerce, so you’d expect me to say that!”

Indeed, but then he put it in more tangible terms, gesturing to an office across the hall: “A few years ago, people like Eric Dodds would never have stayed here.”

Eric Dodds, whom we met at the Next building, is a co-founder and the chief marketing officer of The Iron Yard, a multi-purpose software startup based in Greenville and with operations in Spartanburg, nearby Asheville, NC, and other southeastern locations. You can read more about its operations here.

Dodds grew up in Greenville, and always dreamed of getting away. “Boulder, Portland — that’s where My People would be.” Then, after going to Clemson and working for national branding companies, he came back and noticed that the place where he started out had changed. The Iron Yard’s co-founder and CEO, Peter Barth, grew up in Florida and had worked in New York and the Midwest and was planning to work in Charlotte. He stopped for lunch in Greenville, walked through its famously renovated downtown, and decided this is where he wanted to stay.

Some other time I’ll go into The Iron Yard’s whole business model, which is a combination of “code academy,” business incubators, kids’ classes, and other features. The code academy charges $10,000 for a three-month session, and offers a full refund if graduates can’t get an appropriate job. “We can guarantee an entry-level job, but entry level in this field might be $65,000 or $75,000,” Barth told us. So far they have not had to give any refunds. (More here and here.)

The point for today is an effect we heard about time and again. This was a change in this area’s ability to attract and retain people like Barth or Dodds — whom you might normally expect to find in Boulder, Portland, Boston, and who might have expected to find themselves there.

“Greenville is great once you get here, but it can be hard to get people to come and take a look,” Peter Barth said. Eric Dodds added, “It’s been really interesting rubbing shoulders with people in our classes who say: ‘I’ve gotten here, I’m going into your program, and this is my ticket Out.’ Then after a while they say, ‘I’ve seen this culture, I think I’m going to stay around here.’ It’s been very interesting in stopping the brain drain.”

More on this theme, the dispersion of opportunity, in coming installments. And before this coming week’s State of the Union address, a reminder that the resilient capacity of America is more evident and encouraging city-by-city than it seems in national discussions.

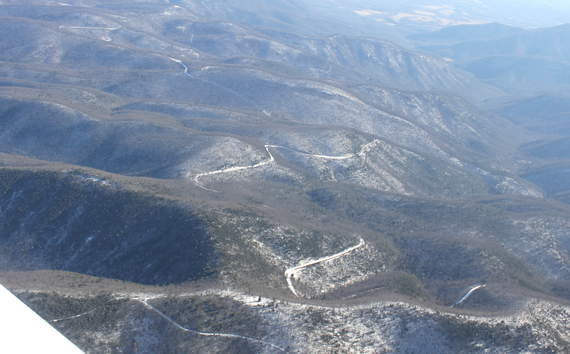

As a closing bonus, in case you were wondering what the Blue Ridge Parkway looks like from above during the Polar Vortex era, here is your answer.