Jim and I spent a lot of time in San Bernardino, California last winter. We were based in next-door Redlands, Jim’s hometown, to report on towns in the West and Southwest for our American Futures project.

When we returned to Southern California a few weeks ago for a conference of town mayors at the University of Redlands, we retraced our familiar paths in San Bernardino. We were drawn to see the town again after the terrible shootings that happened there in December.

Of course the town looked the same after “December second,” a term that has become the linguistic handle in the region for discussing the tragedy, the same way “September eleventh” or “nine-eleven” has become a handle across the U.S. for that infamous date. When I asked people what felt different in the city, some of the language was new. They used phrases like “a show of resiliency,” “a commitment to try to do better,” and “to believe in the city.”

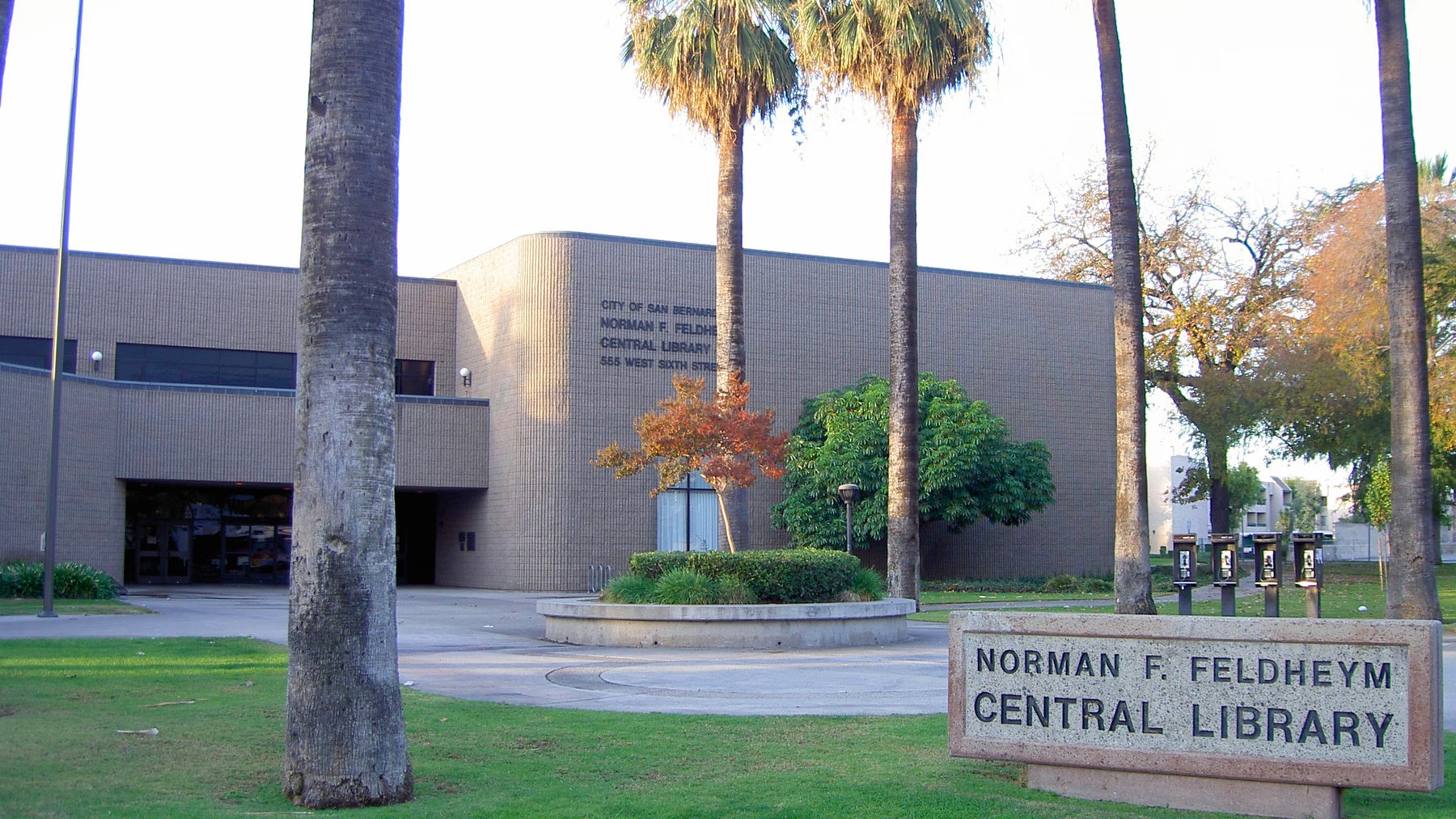

The Central Library, as it is often called, is in downtown San Bernardino. It is surrounded by park-like grounds, but signs remind you that there is no loitering allowed. Despite that, at least one homeless man made himself comfortable lying amid his bags. He was harmless and not exactly loitering, and there were certainly bigger problems for the police in San Bernardino than to chase him away.

When I walked inside, the security guard spotted me immediately; he was clearly waiting for me, in my journalist role, to send me along to the staff. When I asked to stop by the restroom, he grabbed his keys and guided me to the staff restroom, saying thoughtfully that it would be much nicer than the public one.

Like all of San Bernardino, the public library was hit hard during recession of 2008. Before 2008, Ed Erjavek, the library director told me, the budget, which is allocated by the city of San Bernardino, was $3.5 million, and it supported a full-time staff of 31. Today, the budget is $1.5 million, and it supports a staff of 10. One result is that the library open hours have fallen from 54 hours a week to 37 in the central library, and even lower to 20 hours in the branch libraries. [Update: Ed Erjavek has asked me to clarify that he is “hopeful that if/when the city’s recovery plan is approved by the bankruptcy court and implemented, some of the funds will be redirected to the library to offset some of the initial cuts.” I am happy to do so.]

The library copes by grabbing a strong lifeline braided together by generous funders, creative grant-seeking, and an army of dedicated volunteers.

The Library Foundation, an independent fundraising group founded in 1995, has been a staunch and strong driver shoring up the basic staff-and-operations budget from the city to move the library forward. They dedicated $306,000 to replace their nearly decade-old computer hardware and software, a one-time gift that Erjavek pronounced was “beyond my wildest dreams.” The Foundation also donates funds for actual books, e-books, and audio books, and many other projects.

And the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, located in adjacent Highland, California, where it also runs a casino, has donated $40,000 for library books.

As in many libraries, the volunteer Friends of the Library are the grass roots supporters who know their libraries inside and out. In San Bernardino last year, the Friends provided $20,000 for books and more than twice that for projects.

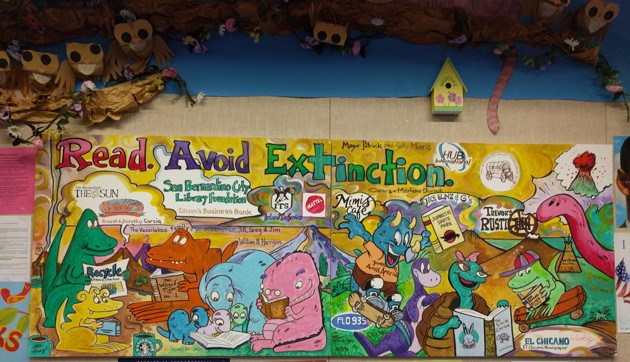

Linda Adams Yeh, the effervescent staffer who manages the programming for the library and the young adults and coordinates the multitude of volunteers, led me around the children’s room, a recipient of Friends’ funds. The children’s area is often the most welcoming room in libraries; San Bernardino’s is bright with hand-painted murals, craft work, and a new set of fish tanks. The room and activities are a draw for the children, as well as a gateway to attract parents into the library.

Volunteers were everywhere. One was a greeter in the main reading room. Another was upstairs staffing the California Room with its archives of local and California history, where a reporter and a professor were working. She told me that lots of people come in to use the genealogy records, which are particularly rich in holdings from the mid-19th century Mormon settlers.

Upstairs, two levels of ESL classes, one for beginners and one for intermediates, were being taught by staff from the Jack L. Hill Lifelong Learning Center. The 20-some students were all ages of Hispanics and, more recently, Asians. More help comes in the form of homework services, literacy, preschool activities, and computer and citizenship classes. All for free. “This is a goldmine,” said Yeh of the library and all the services it helps to offer the community.

Sometimes, unexpected help arrives through unfortunate circumstances. The 200-person auditorium had a nice new carpet, made possible from an insurance settlement from a recent indoor flood. Also, after the December second shootings, the library received a $15,000 grant for library books from the California State Library to support the library’s role as a community anchor in times of crisis. The library also received generous funding for internet, phone, hardware, and a new wifi network under a federal program that helps communities based on the percentage of their K — 12 students who qualify for free and reduced lunch, the proxy for poverty.

I asked Erjavek if he compared notes about their challenges with librarians from other communities at meetings or gatherings. Yes, he told me, and a few were also extremely challenged, but “this is the toughest.” So many times during our conversation, Erjavek repeated a phrase like “We are so grateful for the support we get.” Or “We appreciate the support.” Or “We are grateful for what we have.” Indeed, most of the libraries I have visited have worked on creative fundraising of various sorts. But from what I’ve seen, I would have to agree with Erjavek about San Bernardino that this place is the toughest.

On my way out, I stopped to use the public restroom, since I was curious after being steered away from it when I arrived. It was fine. But I also encountered one of those surprisingly disorienting moments—like when flight attendants hesitate, and pause to remember the name of the city where they’re landing, or when political candidates trip or stumble on the name of the city where they’re delivering the stump speech.