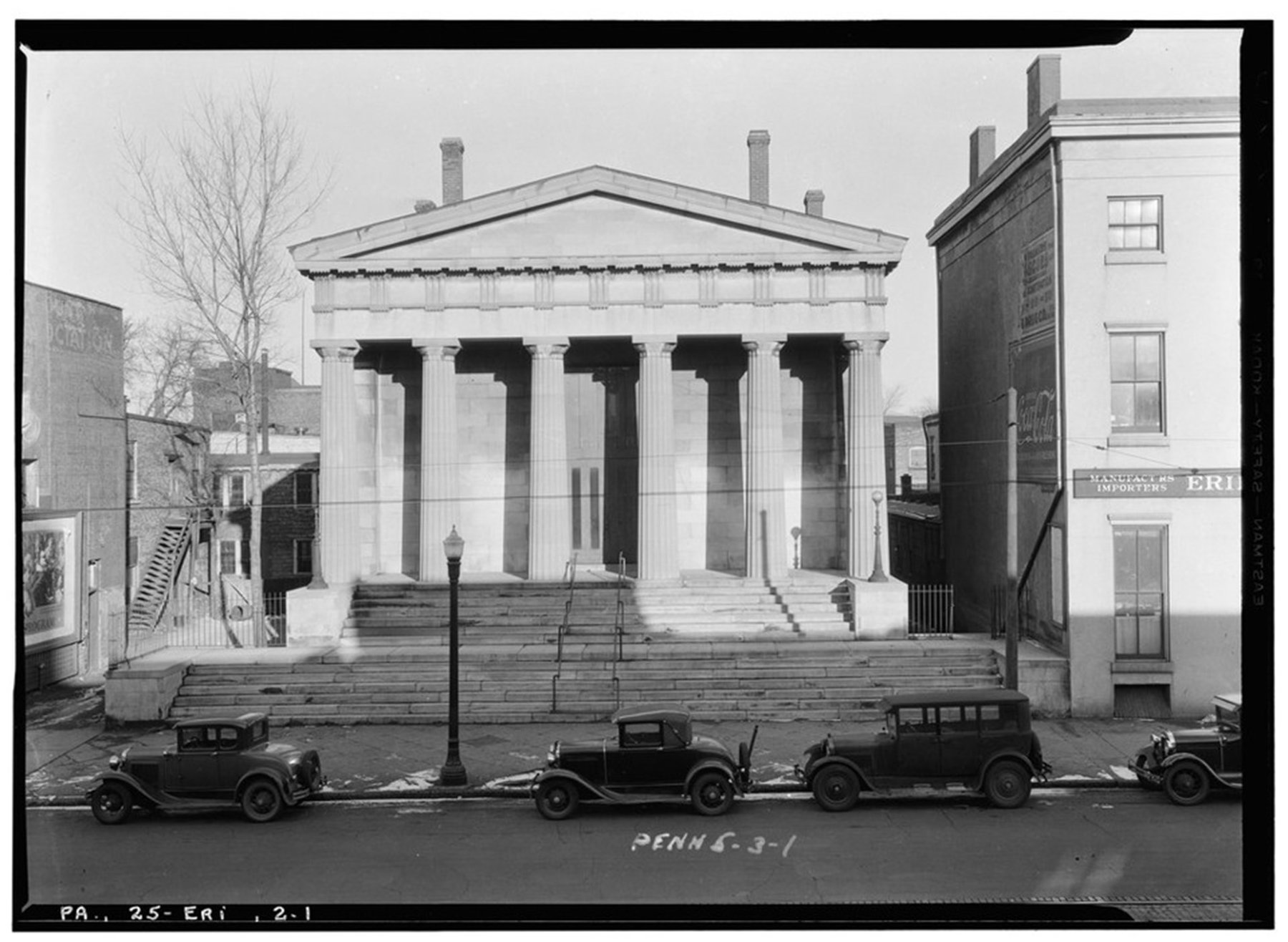

If you walk along State Street in Erie, Pennsylvania, which heads straight through the heart of downtown, all the way to the pier jutting into Presque Isle Bay, you’ll pass the imposing Greek Revival building that was built in the 1830s to house the U.S. Bank of Pennsylvania. When the bank folded after a few years, the U.S. government bought the building for use as the Port of Erie’s Customs House. A series of other identities followed.

Nestled next door to the Old Customs House, as the building is fondly called around town, is the former bank cashier’s house, also part of the museum. It is more modest, like the rectory of a grand church, but confirms that being the cashier came with terrific perks back in the day. The Museum has a number of tenants in other adjoining buildings, including the Erie Historical Society and a yoga studio.

Round the corner to 5th Street and there, set back in a courtyard and in intentional architectural contrast to the formality of the Old Customs House, is the new, glass-front double-story public entrance to the museum. To me, the message of this new architecture beckons: Welcome! This is for you!

* * *

Across the room is a folk-art carousel by self-taught Pennsylvania artist Louis Dartanion Alexatos, who had earlier been a cowboy, a carnival worker, a boat captain, and a fencing instructor. Maybe it takes such life experience to design such a carousel. Besides the standard (but undersized) animals, the top of the carousel features scenes from the Old and New Testaments alternating with figures of, among others, Christ and a grinning devil.

There is so much to see in this museum that I was grateful for the tour around from John Vanco, the museum’s founding director, and from Kelly Armor, the Director of Education and Folk Art. (They are married.) Vanco was barely into his twenties when he was hired. He had graduated from Allegheny College with a degree in art history, completed an internship at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and then returned home to Erie.

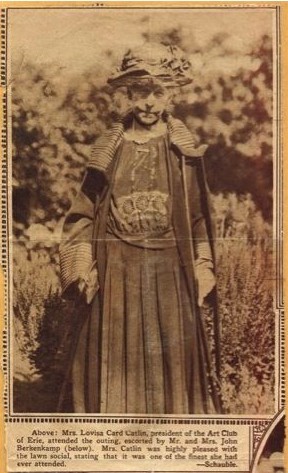

There was nothing ordinary about the beginning of the museum. Unlike the many art museums that make their debuts with a family name and art collection, the Erie museum began in 1898 with a group of artists calling itself The Art Club of Erie. The club members were active in Erie for the next 70 years before ramping way up, launching a membership and fund raising drive, and hiring John Vanco.

Over the first 15 years, they grew, expanded, and prospered with new exhibitions, programs, traveling exhibits to bring in revenue, a frame shop, studios, a darkroom, a theater, a ceramics studio, a music series, and more.

In 1983 came a new name, the Erie Art Museum, and a gutsy move to the Old Customs Building. It was gutsy in a way similar to the Erie Public Library’s move to its new building on the waterfront about a dozen years later, which I wrote about here. Both institutions were early arrivals to rundown, even derelict areas.

We wended our way through the museum’s rooms and halls, up stairs and down, even as far as the old bank vault. One of our first detours was one I always like the best: the back rooms. The back rooms are different from the produced and polished rooms on the public floors. They are more of a glimpse into the thinking and planning of what museums and their curators are about, their dreams, the works-in-progress, and the bits left on the cutting room floor. Here laid out on a long work table was a wonderful collection of Erie decoys, as old as the 1890s. Vanco describes himself as a collector, and he has been collecting wooden decoys for a long time now.

We looked at the decoys, and then he and Armor gave me a kind of quiz, which I passed thanks to my own childhood growing up on Lake Erie, in Ohio. “What do you notice about all these decoys?” they asked expectantly. I offered a few lame tries with “nice carving,” “dark, faded color” before I landed on what I knew would be the right answer: Flat bottoms! I knew the choppy waters of Lake Erie; what could serve an Erie decoy better for not flipping bottom-up than a flat bottom?

Like many other collections and exhibits at the Erie Art Museum, the decoys are connected to the place that is Erie, its people, and its past. Duck hunting has always been important to Erie, from its days when ducks were sent to market, through the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and its annual regulations for hunting seasons and bagging limits.

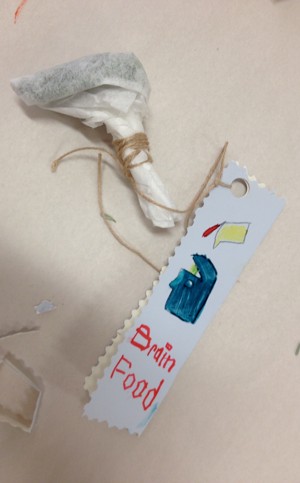

Upstairs in the old bank’s main room, now the Hagen Family Gallery, is something completely different. On display were the semi-finalists in the eighth year of the InnovationErie Design Competition. This represents a great collaboration of folks from Erie’s innovation, technology, business, manufacturing, art, and philanthropic worlds. Innovators and artists submit ideas and designs for products that can be made in or around Erie. This year were, among others, the prototype for heat resistant finger mitts called Grabadoo, more compact and less clunky than traditional oven mitts. Also, a sensor device called Spot the Tot: Car Seat LIFESAVER, which alerts a (forgetful) driver who has unbuckled his own seatbelt that there is still a child in the car strapped into a carseat .

Vanco told me that at least one of the past entries, reCap Mason Jars, has gone to market successfully, a set of interchangeable plastic Ball jar lids with various uses, like shaking out the jar contents or allowing breathing room for lightning bugs.

A local favorite exhibit in Erie is Avalon Restaurant, a soft-sculpture of figures around the counter of a now-closed local Avalon diner. Local artist Lisa Lichtenfels was inspired to create this sculpture after a year working as a waitress in the restaurant. Vanco told me about the number of Erieites who file through nostalgically to see the piece and remember the Avalon.

Around town outside the museum, Jim and I ran into one of the museum’s public art projects. It is called Artist-Designed Bike Racks, and is the product of a collaboration between the museum and some 20 partners and sponsors from private businesses to the Erie Country Department of Health, to foundations and many more. The creative bike racks were designed by local artists and installed at various sites around town.

At the end of our afternoon, Vanco, Armor, and I went outside into the museum’s herb garden. Armor described that this is a kids’ favorite, and it has served as a great tool for getting kids to connect with art, the museum, and an experience that may be novel to many of them. The kids are encouraged, to pick, taste, and feel the plants, and to talk about them. Armor described a small, telling moment when one little boy, a young refugee from Bhutan, was carefully studying all the herbs and then asked, “Do you have the herb for headaches?” You know there was something behind that question. It could have been any number of things, but all of them are about that little boy trying to make a connection between the home he left and the place that he arrived.

For me, a moment like this represents something that is hard to quantify or measure, which is the reach that public and civic institutions like museums and libraries have into a town and the people who live there. We expect them to reach the patrons and donors, the educators and professionals, any of the people who would naturally find their way through the doors. But when they reach young elementary-school-age kids, even refugees, and make a personal connection, then I would say this is a sign that institutions are making a difference. The little Bhutanese boy learned something new and was thinking about something relevant to him in the museum garden in his new hometown. And for it, he’ll probably grow up with a fondness and a story that connects him to the town art museum. That is saying something.