This is the second of two collections of essays and poems written by the students at the Mississippi Schools for Mathematics and Science, in tiny Columbus, Mississippi. The first collection is here.

Students come to MSMS, as the school is called, from all over the state. They live at the school, a free public-residential school, for their junior and senior years. The curriculum is intense in STEM courses and equally demanding in the arts and humanities.

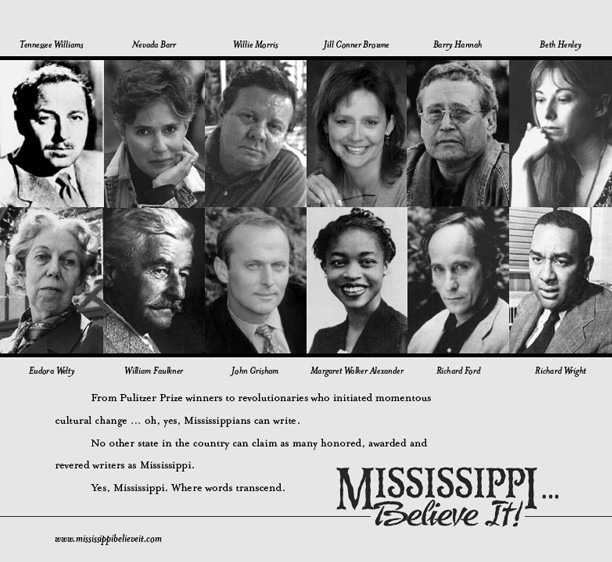

The students certainly read the writers of Mississippi—William Faulkner, Walker Percy, Eudora Welty, Willie Morris, Tennessee Williams, and Richard Wright to name a few. Such a heritage must both inspire the students and terrify them; how could they ever aspire to be real writers from Mississippi? They have two points in their favor. First, Mississippi is a state of powerfully rich (for better and worse) culture and history, with which they can connect their own lives. And second, they are dared and guided by their teachers to examine and write about their own lives in this context.

Connor McNamee is a senior from Florence, Mississippi, which is just south of the state’s capital, Jackson.

Momma’s Boy

Momma’s boy. That’s what Daddy always used to call me when I didn’t act like the other boys. When I attracted looks in McRae’s for dancing and singing along to Britney Spears, he’d tell the gawkers, “What can you do? He’s just a momma’s boy.” When I’d cry, Daddy would say to my aunts, uncles, and grandparents, “He’s just a momma’s boy.” I never saw the bad in being called a momma’s boy; in fact, I took it as a badge of courage because I knew I was a momma’s boy. While the other boys were out in the woods learning to kill deer they’d never eat, I was learning how to make my great-great grandmother’s pecan pie recipe. When the other fathers were teaching their sons to play football, Momma would tell me to study and learn and read and be the best I could because she “wanted the best for momma’s little boy.” I took this advice and inspiration from my mother—as I have taken the advice and inspiration from many other women in my life.

When grade school was over the other boys decided to give me a new name: Sissy boy. This name followed me like a shadow through most of my time in high school. The other boys never saw me as the boy at the top of the class or the boy who always liked to smile. They just saw me as the boy who sat with girls at lunch and listened to pop music. The sissy boy. I couldn’t talk in class without being mimicked; I couldn’t walk the halls without being pushed. All I could do was what Momma had taught me to do all my life: Learn. I buried myself in my studies, aced all my classes with flying colors, and rose to the top of my class like cream on milk. Again, the most valuable lessons I learned during this part of my life did not come from my books, but instead from the women in my life. Through the lessons of Mrs. Holder and Mrs. Porter, my first science teachers, I discovered my love of science because it was able to show me a beauty in the world that I had previously not been able to see anything special in. Through the laughter of Emmie and Annie, the girls I sat with at lunch, I learned the value of making others and myself happy. Most importantly, through Kori Weaver, the girl who stood up in the middle of class and yelled at those making fun of the way I speak, I learned that no matter where I am in the world and how people tell me to be, I am worth something.

In my sophomore year I made the decision to leave my small, private Christian school and attend my junior and senior years at the Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science. Momma accepted this decision with more than a grain of salt. She was finally “losing her baby boy” but she also knew this was the best way for me to pursue the love of knowledge and learning she had put in me since I was her little momma’s boy. The only person who took this decision harder than she did was the momma’s boy who had to leave her behind. What helped me make the decision easier was the classes I would be able to take, such as AP Chemistry, University Calculus, and Microbiology. Even though the classes were definitely difficult, I made Momma proud and excelled in all. By going to this new school I wanted, of course, to get the best possible education, but I got so much more. For once in my life I wasn’t renamed; I wasn’t momma’s boy, or sissy boy: I was Connor. My feminine mannerisms were no longer my defining trait; finally I was seen as the kid who does whatever he can to excel in academics and does whatever he can to see others happy.

This isn’t to say that I resent my name, because they are true. I am that momma’s boy who couldn’t stop crying when my favorite America’s Next Top Model contestant got eliminated and I am that sissy boy who listened to Lady Gaga and Britney Spears instead of Nickleback like the other boys, and I am Connor, the boy who loves who he is no matter what anybody has to say.

* * *

Dancing on the Factory Floor

Working with my dad on sticky August mornings,

we swayed and sweated to the beat of heat presses.

The screens for shirts lifted with hydraulic hisses,

like cats in the night but steadier.

With the whir of a thousand paper airplanes cutting through air,

boards of shirts swung exactly sixty degrees left.

Then massive metal arms plunked down,

dropping with the heavy groan of grandfather falling into recliners.

The reluctant clang of metal provided beats to the dance.On the edges of the shop floor, people would gather.

“Now, I just heard they were moving churches!”

might rise above the rhythm of the presses,

echoing off the highdomed

ceiling and reaching our corner.

“You know, she’s behind on her paperwork.

Been drawn up in a knot about that boyfriend of her’s.”

Their gossip was to our ears

what movement is to the corner of your eye.Dad and I just focused on our dance.

As the hydraulics lifted, I folded a printed shirt onto a belt,

while he smoothed one onto the press with meticulous motions.With the whirring rotation we paused and swayed,

maybe bent our knees to test for stiffness.

As the press clunked back down with a bang,

we moved on the beat, Dad grabbing another shirt to load

while my hands found the corners of a printed one.

Then, like the circling swing of the press,

we just went round and around.

Jenny Bobo is a senior from Okolona, near Tupelo, in northeast Mississippi.

Chiron

To the ancient Greeks, Chiron was a kindly centaur, mentor to great heroes like Achilles, opposite in nature to his warlike, constantly inebriated brethren. To me, however, Chiron was a full horse, with little tutoring skills except to those younger, rowdier foals he was sometimes pastured with. My Chiron was a quiet gelding, complaisant to simple commands and fairly decent at cart-pulling if given a slow pace to match and lots of praise afterwards. He never balked, kicked, jumped, charged, bit, or even pawed at any human: a true representation of the ideal working Shire. It can be said, however, that his training was rudimentary; he knew little of the life of work beyond the occasional short-lived wagon festivities. Perhaps if he’d been worked more in early years he could have put up with that witch. I sure as hell know I couldn’t have, even with a thousand years of training, even from the tutelage of the greatest centaur the Greeks ever had.

The witch herself arrived one balmy autumn midday, shambling up the sidewalk whilst complaining all the while of her stiff hip and every minute inconvenience of her entire drive. The trailer had blown a tire; her phone had died; the entire world was against her. I leaned against a porch column, attempting to blink away the headache her jabbering would soon form. I’d already been out to the gelding pasture twice that morning; both times at my daddy’s beck to “brush them boys ’til they shine.” Indeed, they shone. I’d given each boy a quick bath and scraped away the water with a tined brush; Chiron was the most brilliant of the four, his ebony coat highlighted with russet from a long, sunny summer and his wiry mop of mane coiled into lustrous dreadlocks. Mama cut the witch off from her complaint monologue with a polite offer of refreshment and rest. The hag declined, grumbling about needing to see the horse “right now, otherwise we’re wasting time.” I snorted and leapt off the porch, striding across the yard to the gravel road that meandered across the creek up to the gelding pasture. My parents, sister, and the witch all loaded into a set of ATVs and zoomed ahead of me, plodding along with my eyes on the line dividing the chalky rock road and the silky byhalia. When I reached the feeding stalls connected to the front of their forty-acre pasture, no horses were to be seen, only my father banging on the buckets, mimicking the feeding call for all creatures we have ever owned. The boys rounded the corner from the pine forest, thundering their way clumsily to the stalls. They snorted and pawed, eager for food they would not receive, as my sister snuck around behind them, securing each pipe gate to ensure no escape from the witch’s clutches.

The first three horses proved to be inadequate for the witch; she looked Comet, Zeus, and Apollo over without placing one finger on any of them, denouncing each to be “not what she needed.” With each word she slurred from her tobacco-stained teeth, my hatred of her grew. This woman had already been to our home twice, viewing our horses then rattling off after several hours with a declaration of “I need time t’think.” My parents both kept inviting her back, hoping to sell a horse after almost a decade of no sales. She oozed superiority and condescension; she treated my friends like trash, slapping their hocks and jerking their halters down so she could meet their eyes with her own beady, black, soulless gaze. She had yet to inspect Chiron; from what she’d described as the right horse to pair with her other black Shire, I knew she’d settled on Chiron. After the same rough once-over, she proclaimed Chiron to be “good.” I jammed my greasy hands into the pockets of my mud-splattered jeans to stop my body from trembling with anger. She struck a deal with my father for a trial period, and off she whisked my sweet brother. My tears had hardly any time to seep into the dirt smears on my cheeks before the trailer bobbed down the highway and out of sight.

It had been close to five months since she taken him, and the first spider lilies were shooting up from Mama’s raised flower bed. The crone called during a Saturday lunch after a morning of mulching and pruning, explaining that it hadn’t worked out, Chiron had been “too lazy t’fix after all.” So she brought him back the following Thursday. It’s a blessing I wasn’t there to see her, for if I had been, she’d have been sent on her way with a few less teeth. My Mama was the only one home and, therefore, the only one available to help unload Chiron. He shuffled from the back of the trailer, his lips drifting over the soft tufts of milo. He was not the same horse. He’d lost weight, now lacking that roll in his step that made his jolly belly jiggle; his eyes were glassy, blank of all previous expression, even anger. The witch towed him towards the paddock; he tottered behind in a stupor. His gaze wandered from the ground to Mama’s boots then up to her face. If asked today, she’d recall his eyes “lit up like someone threw a match on a brush pile in a drought.” His spark, I believe, was reignited in that instant. And how he chose to rejoice in its return will forever be the reason I believe horses are smarter, and wittier, than people. He jerked to a halt, snapping the witch’s arm back to near his shoulder. She squealed and thumped him on the face, the face! Even my Mama would’ve slapped her for it, but Chiron beat her to the punch. He whipped around, situating his haunches near the hag’s face, and double-kicked the woman’s bad hip, the one she’d bleated about since I’d first met her. Mama says she might’ve actually given a little delighted whoop before fetching the horse and helping the witch to her stubby feet.

The crone wasn’t injured badly, just given something real to complain about for once. She left without much fuss; perhaps, in a moment of clarity, she’d realized her cruelty and just how much injustice she’d done to Chiron. That day after school, I strode quickly up the hill, over the creek and culvert, and through the paddock gate, dreading to see Chiron, broken and weak as my Mama had woefully described. I whistled and glanced around, seeing none of the geldings. Then, their hoofbeats echoed from the fringes of the pines, and a resplendent sight, very much like the day Chiron had left me, emerged a moment later. I marveled at the skinnier figure of my friend, head high as he led the procession of proud Shires into the bodock paddock. His eyes were not glassy; his countenance displayed his usual charm. I yanked the carrot bag from my shoulder and dispersed the treats quickly, my eyes flickering across Chiron’s form as he walked and ate, searching for signs of trauma. Although he was smaller and weaker than his normal self, he showed no feelings of pain, much to my delight. He nudged me, and I wrapped my arms around his arched neck, draped with shaggy coal tresses. This time my tears fell on Chiron’s shoulder and were given ample time to soak into his dusty, matted hair, christening his deliverance from hell.

Although I saw no wounds on Chiron that day, I soon realized there were still plenty lurking in his mind. It took months before he didn’t flinch at a hand being raised or run from the sight of a wagon. For the longest time he wheezed pitifully when confronted with a harness. We slowly coaxed him back into his former self, helping him regain the confidence the witch had stolen from him. Today, he has been rehabilitated to his full being, once again the sage-like elder to the rambunctious weanlings of any given year. I give you my word that I saw him hold lessons in decorum for his little adopted brood in the clover patches just this spring. As for the witch, she was never heard from again, and it’s a good thing, too. Bad things can happen on a farm.