It is important because so much of the future of American economic, cultural, and civic life is now being devised and determined at the local or state level. Educational innovation, promotion of new industries and creation of fairer opportunities, absorption of new arrivals (in growing communities) and retaining existing talent (in shrinking ones), reform of policing and prison practices, equitable housing and transportation policies, offsets to addiction and homelessness and other widespread problems, environmental sustainability—these and just about every other issue you can think of are the subjects of countless simultaneous experiments going on across the country. Voters, residents, and taxpayers need to know what is happening (or not), and what is working (or not), in their school systems, and their city councils, and their state capitals.

It is imperiled for obvious reasons. What has happened to media revenues in general has happened worst, fastest, and hardest to local publications, newspapers most of all.

This is part of the reason Deb Fallows and I have been reporting on local-journalism innovations (and successes) we’ve seen, such as the Report for America initiative I mentioned in June, and the business model behind the last family-owned daily in Mississippi, The Commercial Dispatch in Columbus (and, long before that, the former alt-weekly that has become a leading statewide news source in Vermont, Seven Days, of Burlington).

No one of these models or examples will necessarily apply in other places or circumstances. But any illustration of success is worth noticing, for tips.

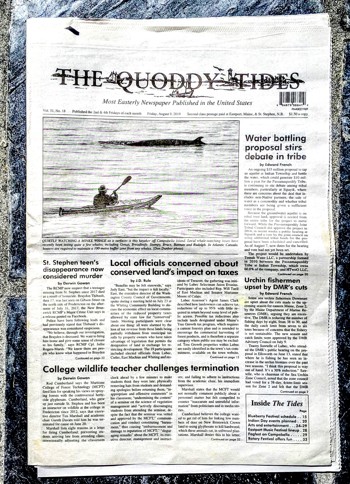

This brings us to The Quoddy Tides, the twice-monthly, family-owned and -run newspaper that has a print circulation several times larger than the population of the city where it is based.

The home city is Eastport, Maine, whose library Deb wrote about recently, and which we described in our book, Our Towns. In its heyday as a sardine-canning capital, Eastport had a population of more than 5,000. Now the canneries are gone, and the year-round population is about 1,300, and nearly everyone in town holds a combination of jobs—lobster fishing, seasonal tourist businesses, work at the commercial port or in forestry, small crafts or art studios—to make ends meet. But in this setting, The Quoddy Tides has a paid print circulation of just less than 5,000, and now has more than 50 years of continuous operation. Its editorial and business office is in a white clapboard structure that at various times was a fishing-company office and then a Christian Science church, along the bay front in Eastport’s small but architecturally distinguished downtown. It is run on a shoestring, but it has some 20 contributors and correspondents in the region, and it is full of both articles and ads, and it matters in its community.

Part of The QT‘s circulation secret is similar to that of Seven Days, in Vermont: It is aimed at an audience, and market, beyond its immediate hometown base. In addition to news of Eastport, The QT covers that of other down-east Maine towns such as Lubec, Machias, and Calais (pronounced like callous), and adjoining maritime islands and towns in the Canadian province of New Brunswick. It also has a substantial mail circulation, reaching subscribers in 49 states who are originally from the area, or have visited, or feel some interest or connection to it. (South Dakota is the outlier. People of Sioux Falls and Rapid City, c’mon!)

Also, like The Commercial Dispatch in Mississippi, the paper’s family ownership means that it can spend its modest resources as it chooses. It is not under external-ownership pressure to meet regular profitability targets, which has sent so many small papers into cycles of cutback and decline.

But when I spoke with the husband-and-wife couple who run the paper, Edward French and Lora Whelan, they emphasized that it was the kind of journalism they provide that has allowed them to survive.

The Quoddy Tides—named for the Passamaquoddy Bay on which Eastport sits, which feeds into the Bay of Fundy—was founded by Edward’s mother, Winifred, in 1968. She and her husband, Rowland, a doctor, had moved to Eastport from Arizona in the early 1950s, and stayed there to raise their family. (“My mother was looking for someplace not quite as hot,” Edward told me in The QT‘s office earlier this month. “Coastal Maine qualified.”) Rowland became a leading local doctor, with a clinic now named in his honor. One of Edward’s brothers, Hugh, also lives now in Eastport, where with his wife, Kristin McKinlay, he runs a museum and arts organization called the Tides Institute.

In the late 1960s, as the family’s children were growing, Winifred decided that the community needed a newspaper. A previous one, from the town’s sardine-canning days, had gone out of business in the 1950s. “She had no newspaper experience,” Lora said of her mother-in-law. “But she thought these communities really needed a voice. So she talked to other small newspapers and had correspondence with people all around the country about how she should set this up.” After a year of research, she launched the paper in 1968.

Edward, then elementary-school age, grew up helping address papers for mail subscribers, and with the page layout. In those days, a fishing boat took article text across the water to a layout shop in Deer Island, Canada, and then another boat would carry the pasted-up pages back to the U.S. for printing.

Then and now, the striking characteristic of the paper is its density of local news. The most recent issue, when we visited, was 40 pages long, with many dozens of purely local, information-packed news stories.

For instance, the front page (at right) had five local stories: about the Passamaquoddy Tribal Council’s effort to defend water rights; about limits on sea-urchin fishing (a quickly growing market, mainly for export to Asia); about the impact of new tax preferences, for land conservation, on local tax revenues; a crime story; and one about an academic-freedom dispute at the local Maritime College of Forest Technology. Plus, a picture of a kayaker viewing a Minke whale—of which we saw large numbers in the bay.

In the rest of the paper you have: high-school sports. Commercial shipping schedules and tide tables. Gardening and cooking tips. Religious news. Birth and death notices. Puzzles. Local city-council roundups. A long editorial and letters-to-editors section. Everything.

“I think it’s important for newspapers not to keep cutting,” Edward told me at The QT‘s office. “If you keep cutting, there’s less and less reason for people to buy the paper. If you want to keep a healthy circulation, you have to make the investment in reporters and providing the news that people can’t find anywhere else.” If there is a “secret” of the paper’s success, he said, it is “that you’re providing information that people can’t find any other place.”

Both Lora and Edward emphasized that the paper’s twice-a-month publishing schedule—the second and fourth Friday of each month, with a built-in cushion for them in the months that have five Fridays—gives them an advantage, in forcing them away from the daily or breaking-news stories that their readers would already have learned about elsewhere.

“I believe that daily newspapers struggle because they’re so often repeating what’s already been presented, either in social media or on the television news,” Edward said. “But when you have a local newspaper that is presenting news people aren’t going to find anywhere else, I think there will always be a need for that. I think that will allow local newspapers to survive very well.”

Unlike her husband, Lora is not originally from Eastport. She grew up in New York; some of her relatives ran a small newspaper in Santa Barbara, California; and she originally came to Maine, before she met Edward, to work on an economic-development project. They met, and married, and she became involved with the newspaper. Now she is the assistant editor and publisher, and does much of the local-news coverage.

“I don’t know what journalism schools are doing these days, but I really wish they would focus more on local news,” she told me. “It can be boring, I mean reallyboring, to go to city-council meetings every month, and county-commissioner meetings every month. But at the same time, it’s incredibly important. And at least once a year, something will come out that’s incredibly important, and that you would not know if you hadn’t been there.”

“Those are the kinds of stories that local people need to know, and want to know, and that are getting lost with some of the papers that don’t have the resources, or don’t understand how important it is to cover those boring meetings month after month.”

“It’s not exciting most of the time,” she said—and Deb and I knew what she was talking about, since we’d been to an Eastport City Council meeting that she was covering. “But it’s critical. It’s like how most of us live our lives. Not terribly exciting most of the time—but, you know, we have these moments!”

Edward had an aw-shucks, self-deprecating manner when talking about his newspaper’s influence and record. Maybe this is The Maine Way; maybe it’s just him. But he wasn’t afraid to seem earnest when talking about why he believed that local journalism mattered.

“I think we provide quite a bit of investigative reporting, and try to get into the meat of what’s happening so that people can make informed decisions. We really try to provide a voice for people in our communities that might otherwise not have a voice, so that people in power have to address their concerns and be held accountable.”

“I think that’s really the basis for a healthy democracy,” he said. “I think without community newspapers, democracy will really suffer.” It’s worth noting at this point that we’ve been following the Eastport and Quoddy Tides saga for more than six years now, and what Edward and Lora said about their paper matches what other people in the community have told us as well. It’s not unusual to overhear people saying, “Well, I saw in the Tides …”

Lora said that in a town as small as Eastport, she and her husband and their contributors knew that every day they would encounter people they were writing about, and people who read their paper. “It’s a delicate balance in a community this small,” she said. “We’d walk into the IGA”—the local grocery store—”and people would come up to us waving a story we’d written.” For a long time, she said, she and Edward didn’t have a phone-answering machine, because they didn’t want to deal with some messages.

But overall, she said, “actually it’s a blessing to feel that trust that people have in you. They come up to you and say, ‘This is what I’m worried about. Is there any way you can look into it?’ Sometimes we can. Sometimes we cannot. But it is a beautiful feeling to have someone trust you like that.”

The Quoddy Tides model may not work in other communities, and it may not work forever even in this one. But for now it’s a useful illustration of the way journalism, community, public discourse, and civic engagement can interact in a positive cycle, rather than in the destructive ways we’re all so familiar with.