We made this latest trip home from Erie on a quiet Monday afternoon. The weather was warm and clear. We marched through our departure routines: return the rental car, gas up the plane, and since we knew some weather (in airplane talk, “weather” means “bad weather”) was predicted along our route, file an Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) plan for the trip home in instrument conditions, meaning we would be following instructions from the air traffic controllers (ATC). Also, high on my list was a stop at the produce stand I had spied across from the airport to pick up some tomatoes, honey from the local hives, and corn that was still in its prime this much farther north.

We were cleared for takeoff on Runway 24. Runways are laid out where possible to match the prevailing wind, and you choose which runway to use and which direction to take off based on the winds at the time you depart. Ideally you want to take off, and to land, flying into the wind—with a headwind, not a tailwind—because that reduces how fast you need to get going along the runway before lifting off, and how fast the plane’s speed relative to the runway will be when it touches down.

The ATC gave us these instructions: climb and maintain 3,000 feet, expect 5,000 within one-zero minutes. The ATC language is very programmed, designed for efficiency and clarity, and also, at this point, to preview upcoming expectations in case you lose radio contact. We circled around to head south toward home, and I looked back and across through the pilot-side windows to see the town of Erie and the beautiful Presque Isle peninsula with the Bay to the south and Lake Erie to the north.

It wasn’t long before the first clouds materialized ahead of us. We had cross-winds at about 5,000 feet, and you could see that the clear, flat shear of wind seemed to hold up the bottom of the clouds like a tabletop. We were listening on the radio to ATCs guiding planes in the Cleveland Center airspace by this point. This airspace of this part of the country is quiet compared with the busy Atlantic coast, and it is buzzing compared with the quiet spaces of Wyoming or Montana, where we could fly for hours with no contact.

A dramatic foggy-cloud layer was developing ahead of us, and we were trying to decide if we should request an altitude from the ATC that would be below the clouds or above them. We often choose high when we have tailwinds, which are likely to be stronger the higher up you go. And lower if we have headwinds. Frequently, there will be pilot reports of flying conditions, like “smooth ride” or “light chop,” which the ATCs will relay to other planes heading into that airspace.

We broke through the layers at just about 5,000 feet. There were still occasional cloud buildups to the right or left, and we sometimes requested course changes 10 or 15 degrees so we could dart between them. ATCs have no problem allowing you to do this, if you can remain well separated from other planes.

Cruising along, skimming the top of the cloud layers rewards you with the glory of it all. The sun is above you. The clouds are at eye level. You can peer down through the breaks to see farmlands, winding rivers, and geometric highways. You can spot quarries and prisons, schoolyards, and backyard swimming pools.

The cooling towers of the nuclear plants make their own clouds, which rise and mingle with those of Mother Nature.

Other strangers appear in the sky: sometimes there are “jumpers” who are sliding out of planes and floating down to earth by parachute. Sometimes there are low-flying gliders or dirigibles. In the distance, we’ll see the profiles of big jumbo jets and 747s. Occasionally at low altitudes, birds will come out of nowhere, unexpected and dangerous. And near storms, we might see the drama of lightning.

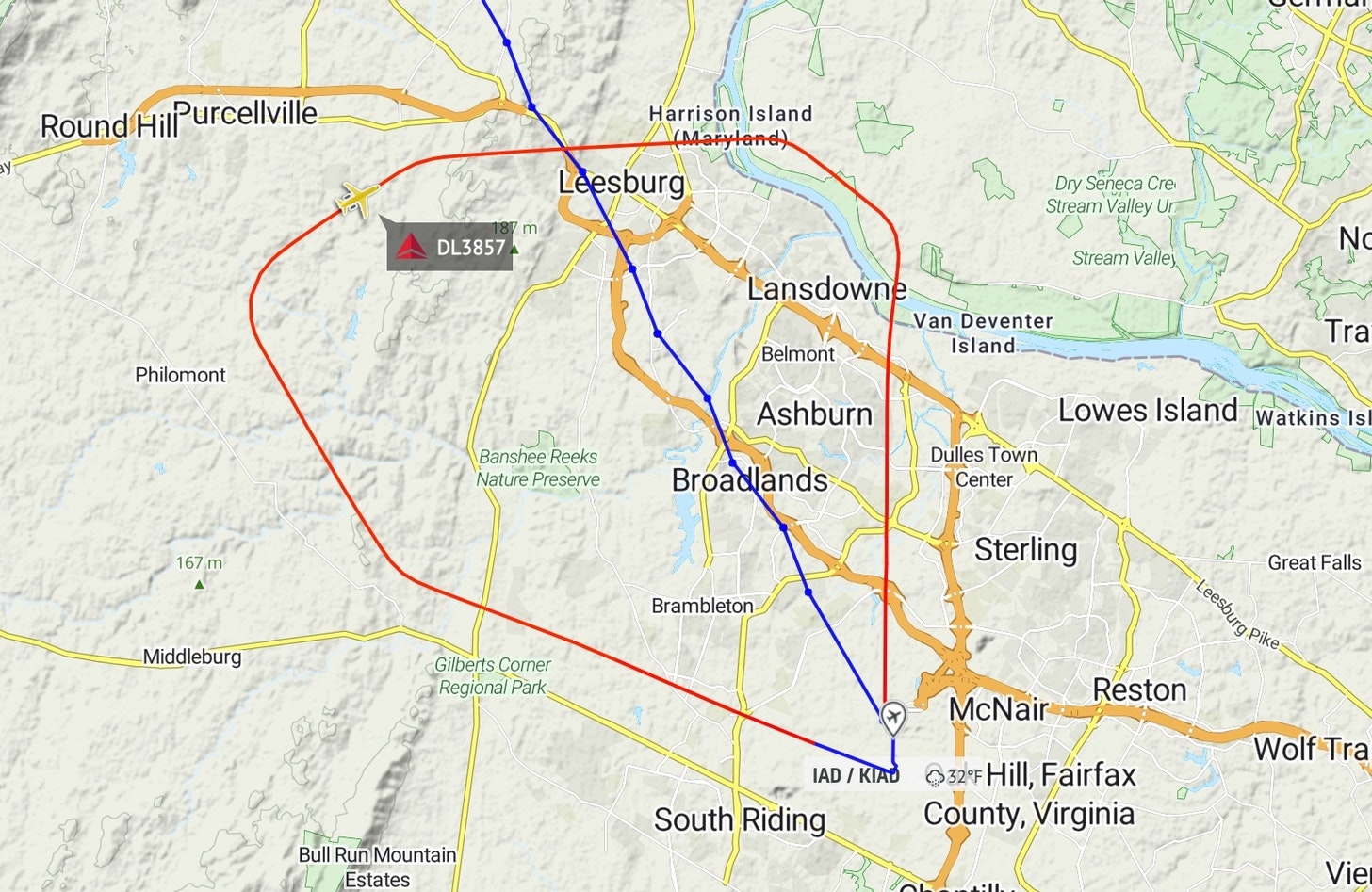

We exited Pennsylvania, flying over Amish country and entering Maryland. The rains had passed, but the clouds were stalled, thick and heavy. We were getting near the D.C. airspace, which is always busy and has become more intense since 9/11. Since then, a Special Flight Rules Area, or SFRA, has been in place circling Washington D.C., and its suburbs require a special clearance for all planes entering or exiting it. Our home-base airport in Gaithersburg, Maryland, is outside the inner Flight Restricted Zone, or FRZ (called “freeze”), over downtown D.C.—essentially a no-fly zone for everything except military aircraft and airliners heading to D.C.’s National airport. But Gaithersburg is inside the SFRA, so we have to file flight plans with our intended time of entry or exit before each flight, and check in with ATCs while we’re in the restricted area.

The end of the flight today was easier than some. The weather had scared off the usual training flights that often clog the space around Gaithersburg, also known by its call letters KGAI. The “instrument approach” for KGAI leads straight in to Runway 14. When the winds are coming from the north or west, you have to do a sort of U-turn to get oriented to land in the opposite direction, on runway 32. But winds were conveniently coming from the south, so we were able to head straight in. We hear the 500-foot alarm notice, as usual, and watch for birds and any stray wildlife crossing the runway. We land, smoothly. We slow down. I crack open the door for some fresh air. We’re safely home. Always a nice feeling.