Introduction, by James Fallows

We’re living through an unusually important moment in the American saga. The strains and failings of the national model–political, economic, in civic-inclusion–are as intense as they have been in many decades. But the opportunities are also exceptional. That has been the theme of other posts on this site, for instance this and this.

Two long-time authorities on both the why and the how of efforts toward national and regional renewal have a proposal about seizing the moment. Patrick Doherty is co-author of The New Grand Strategy and co-founder of the Long-Haul Capital Group, which is dedicated toward steering private investors toward “sustainable prosperity” objectives. Christopher Leinberger is an author, scholar, real estate developer, and consultant on urban-development strategies and related issues. (One of his influential articles was “Here Comes the Neighborhood,” for The Atlantic in 2010.)

Together they offer a proposal for making transportation the center of efforts for economic renewal, at both the national and the regional/local scale–and also efforts for inclusion, socially and politically. They make an economic, social, environmental, and civic argument for an infrastructure and transportation strategy based on “walkability” – a goal that, according to surveys they cite, a clear majority of Americans view as a significant plus.

They also suggest a variation on the now-conventional wisdom (including here) that the most useful precedent for this moment is either Franklin D. Roosevelt, in coping with the Great Depression, or Lyndon B. Johnson, in promoting civil rights legislation. Instead, they say, the relevant models for Joe Biden, a Democrat, are two Republicans: Abraham Lincoln, and Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Here is their case:

The Biden-Harris Administration can strike a grand bargain on transportation. Here’s how to do it.

By Patrick C. Doherty and Christopher B. Leinberger

Patrick C. Doherty is co-author of The New Grand Strategy: Restoring America’s Prosperity, Security, and Sustainability in the 21st Century (St. Martin’s Press, 2016). He lives in Cleveland, Ohio.

Christopher B. Leinbergeris author of The Option of Urbanism: Investing in a New American Dream (Island Press, 2009). Doherty and Leinberger are partners in Places Platform, LLC. He lives in Washington, D.C.

Finding the Radical Center

President Biden’s infrastructure plan contains the seeds of a powerful new economic engine for America’s 21st century. If implemented properly, it can deliver on his promise of more jobs, higher wages, increased government revenues, lower emissions, and racial equity. But it can also deliver on conservative and business objectives by reducing the ratio of federal funding, increasing private investment, and creating more certainty.

Why: Transportation Investments Trigger Economic Growth.

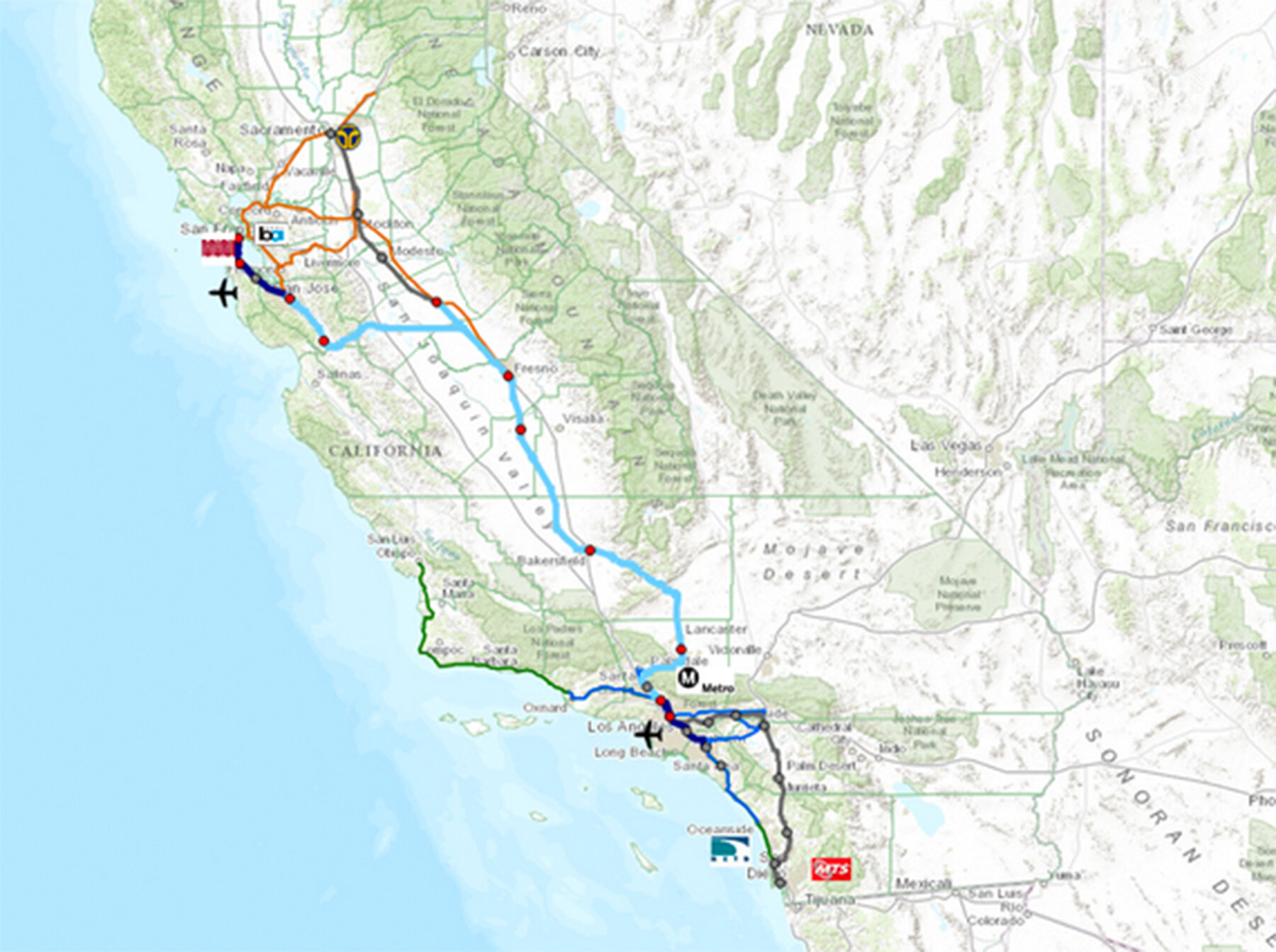

Let’s be very clear: the core of this infrastructure bill, new funding for transportation and housing, is not “more stimulus.” As President Biden and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg are fond of saying, it is an economic reset comparable to President Lincoln’s funding for the transcontinental railroad and President Eisenhower’s funding for the interstate highway system. And it’s the kind of productive fiscal injection for which the Federal Reserve has been calling for years .

Transportation infrastructure by definition enables the flow of people, culture, and commerce, reducing the cost of exchange. Since colonial times, government-funded transportation has enabled America’s economic development. In the 1670s, King Charles II ordered his colonial governors to build a post road to serve the increasing numbers of English colonists from Boston to New York. Thomas Jefferson signed legislation creating the “National Road” to cross the Appalachian Mountains and open the Ohio Valley to settlement. The New York State-funded Erie Canal opened up the Great Lakes and allowed New York City to eclipse Philadelphia.

But the transcontinental railroad did something new and bigger. With a rapid and standardized transport network spanning the continent, we were able to turn our nation of regions into a single U.S. market. Cities could grow because food could be delivered fresh from a bigger greenbelt. Companies could grow because they had a bigger market to serve. And with growth came jobs. For sixty years following the Civil War, our railroad-powered economy made America the wealthiest nation on earth. Immigrants arrived, found jobs, built a house, built a business, and created more demand. Railroads were at the center of that transaction, reducing costs–once the railroad monopolies were broken up. Trains would bring resources into the cities and factories and bring immigrants to the land.

Not surprisingly, after the U.S. won the Second World War, Washington did not try to revert to the 1930s status quo. Instead, with immigration still curtailed (until the immigration-law changes of the mid-1960s), our business and elected leaders re-aligned the economy around a different source of demand. A massive post-war housing shortage in our cities was redirected into demand for suburban housing. This was accomplished incrementally but methodically through the GI Bill, the Civilian Production Administration, Truman’s industrial dispersion order, and Eisenhower’s interstate highway act. And for the better part of second half of the 20th Century, it worked. The U.S. economy grew from 1950-1969 more than any time prior.

Today, that car-dependent suburban economy, now also at seventy years old, has run its course. The demand for exurban housing that collapsed in the 2008-9 Great Recession will not return, notwithstanding anecdotal reports of wealthy New Yorkers decamping Manhattan for splendid suburban isolation in Connecticut and Florida. America’s emissions and resource over-consumption has devastated our own land and the planet’s life support systems. But the racist effects of car-dependency have also torn our social fabric. While redlining may be part of the past as a formal policy, the damage was done and the hollowing out our urban cores continues, devastating communities of color and low-income families; fueling the cycle of desperation and dysfunctional policing that is ripping us apart.

“The car-dependent suburban economy, now also at seventy years old, has run its course… We’re at the end of a long macro-economic era and the design of our 1950s vintage economic engine is the problem. If we just follow the post-Cold War economic recovery playbook, the inequalities and unsustainability will actually destroy the American experiment.

“Fortunately, a new land use concept is showing us the path to an inclusive American Dream. …Livability driven by walkability is already at the heart of our most economically productive cities. Big cities like New York, Boston, and Washington, DC, and a few smaller ones like Greenville, S.C. and Sioux Falls, S.D.—have all doubled down on walkability in the last decade.”

Diagnostically, in other words, our current economic dysfunction is not a periodic business-cycle downturn. We’re at the end of a long macro-economic era and the design of our 1950s vintage economic engine is the problem. If we just follow the post-Cold War economic recovery playbook, the inequalities and unsustainability will actually destroy the American experiment.

Fortunately, a new land use concept is showing us the path to an inclusive American Dream. Metros like Charlotte, N.C. or Chattanooga, Tenn., or Austin, Tex., or Minneapolis, Minn., that invest in a portfolio of mobility solutions are able to offer the most successful mix of lifestyles from walkable urban to walkable suburban, to traditional subdivisions. Livability driven by walkability is already at the heart of our most economically productive cities. Big cities like New York, Boston, and Washington, DC, and a few smaller ones like Greenville, S.C. and Sioux Falls, S.D.—have all doubled down on walkability in the last decade.

This is not about skyscrapers and apartment blocks. It’s about convenience, knowing your neighbors, and getting time back to spend on your family, your start up, or your passion. It’s not accidental that Disney’s Main Street USA delights visitors—its walkable scale idealizes a time before cars and policy segregated our towns by use, income, and race.

This is no passing trend. The National Association of Realtors, hardly a liberal trade association, has consistently measured demand for homes providing walkable lifestyles at over 50 percent of prospective homebuyers for more than a decade – and most recently, at an all-time high of 70 percent. Market data shows NAR’s surveys are correct: walkable real estate in the 30 largest metropolitan areas has over a 100% price premium per square foot over the drivable real estate alternatives, demonstrating vast pent up demand. Walkable places, whether center city, urbanizing suburbs, or small towns, have had a market share growth 4-6 times faster than the growth of drivable regional malls, business parks, and subdivisions.

Yet with Cold-War-era Federal subsidies still distorting markets, and zoning ordinances making new walkable places illegal to build, the cities that have enjoyed the benefits of walkability are overwhelmingly more the exception than the rule, and tend to be bigger and wealthier.

In other words, these housing price trends are driven by scarcity. There is simply not enough walkable land connected to transit to keep up with increasing demand in the market. A recent study estimated that the U.S. is short some 7.5 million, primarily walkable, housing units, the direct cause of the affordable housing crisis and a major contributor to homelessness. We estimate that just building this needed new housing will increase the GDP by approximately 1% annually over the next decade. Economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimate that “stringent restrictions to new housing supply” have “lowered aggregate U.S. growth by 36 percent from 1964 to 2009”, which add up to trillions of dollars of lost growth.

What: A new vision for transportation in the US

This is a policy failure born of obsolete ideas enshrined as law and it’s long past time for a big change. In the American Jobs Plan, the new Administration delivered a largely-unnoticed but revolutionary shift in spending priorities. Throughout the post-World War II era, Federal spending had followed a general distribution of 80% for highways and 20% for transit and rail. The Biden-Harris administration proposes to dramatically shift that ratio, with $115 billion for highways and roads and $165 billion for transit and rail. That roughly equates to a 40:60 ratio.

That’s why this is more than just stimulus. Just like Lincoln and Eisenhower, the Biden-Harris Administration has identified a strategic opportunity for advances in transportation to unlock decades of economic growth. The massive pool of pent-up consumer demand for walkable lifestyles can only be released through sustained investment in higher-capacity, lower footprint mobility solutions—like high-frequency bus service, bus rapid transit, streetcar, light rail, commuter rail, and inter-city service. That’s because walkable places are defined by proximity and human-scale, and cars require too much space between buildings. Period. Certainly, future innovations for high-capacity transit, such as autonomy, or modularity, can be layered into the nation’s mobility fabric, but we don’t have to wait for more R&D—and we cannot afford to.

The Biden-Harris administration’s 40:60 ratio enables the nation to provide the planning and capital resources to each of the 300+ U.S. cities of 100,000 people or more with Chicago-level transit access. This, in turn, allows the next generation of housing, economic innovation, and growth to be physically located along those mobility systems. This must also become permanent, meaning “40:60” should remain the mode split ratio in future transportation bills.

This is the “radical” part of this radical centrist idea; a decisive break with the past that is long overdue. Funding will ensure that the localities serving the 83 percent of Americans who live in urban areas would have the planning and construction dollars to create a corridor and grid plan for streetcar and light or commuter rail that would provide the backbone of high-quality, high-capacity service. Clearly, not every American wants a walkable lifestyle, but for the 70 percent of Americans who do, according to recent surveys, they will be able to live their American Dream.

Imagine shoppers walking home with their daily bread. Parents picking up kids from school on foot or bike. Retirees being able to age in place with many more years of independence. Every third road arterial could be converted to transit, walking, and biking with appropriate increases in density to facilitate the walkable lifestyles Americans want. Bus routes would not be bone-jarring, long-distance ordeals, but part of a short-haul feeder system, bringing commuters to their closest high-capacity line. Bikes, scooters, and a rapidly-electrifying fleet of automobiles would then be use more for last-mile trips than as the mainstay of daily commuting. For smaller cities and towns, funding would be available to create targeted, effective rural transit solutions or improve/expand existing networks.

Because of the increase in density, going forward, all new rail service should be designed for both passengers and freight. It’s a simple rule of cities that as density increases, average speed of surface vehicles slows. This friction can be addressed by having freight service run during off-peak passenger hours. And by connecting the transit system to office, manufacturing, warehousing, and other centers of production, employers can save billions by reducing lateness and absenteeism due to traffic congestion, all while being closer to their customers.

With this vision clearly articulated, federal funds for fix-it-first can become “fix-it-right.” That is, removal of divisive inner-city highway segments can be coordinated to optimize the regional highway system and local road grids to support the new regional transit network. This would include safety measures to protect the increased numbers of pedestrians, bicycles, and scooters, signal priority so that feeder busses move through traffic efficiently.

Federal support for affordable housing should also be prioritized around these new transit corridor/grid networks. Rather than creating new concentrations of poverty, providing incentives with minimum affordability mixes for all jurisdictions along these densifying networks will create more diverse, mixed-income communities and begin breaking the cycles of structural injustice created by redlining and car dependency.

And with 40 percent of funding dedicated to maintaining a high state of repair for our highways and roads, moving within and through the non-walkable parts of our land would be much more safe and pleasant.

How (Part 1): Framing the Grand Bargain

Universal wins

Regardless of partisan affiliation, putting Americans and our capital back to work by giving Americans the lifestyles they want is a universal benefit. This is simply a basic role of the Federal government: ensuring healthy, macroeconomic stewardship. With financial and human capital lined up to tap into deep pools of consumer demand, trillions of dollars of new value can be created, fueling wages, government revenues, and investment returns alike for decades. That’s why this is an inherently centrist big idea.

And because transit-enabled walkability is not only what many Americans want but is also the pathway with a much lower carbon emissions profile, America will effectively break through a major barrier to addressing climate change—making money in the process. Indeed, leading urban planner Peter Calthorpe has estimated that building these kinds of walkable communities will result in a reduction of more than 88 percent of carbon emissions from metropolitan sources. Household finances will improve as well; when three car families go to two or two car families only need one car, families will save on average of $8,000 per year per adult on the cost of a car, while gaining more convenient access to jobs and schools.

That leads to another universal win: improved public health. Automobile commuting and the car dependency of our communities has been shown to be a leading cause of America’s obesity and heart disease epidemic. The mere act of shifting from driving to walking—including walking + taking transit—reduces the incidence of these two killers. And when physical activity increases and you know people in your neighborhood, psychological health improves. Currently, 42.4 percent of Americans are clinically obese; 300,000 people die each year from preventable obesity-related causes and the annual cost to the economy of the epidemic is close to $150 billion annually.

There would also be improvements in local governments’ fiscal health, via a transition to walkability. By reducing population dispersion even moderately–by reducing lot width, allowing duplexes and row houses, adding accessory dwelling units–will result in a significant improvement of local government revenue for the same cost of infrastructure and services. A mile of road–combined with the sewer, water, fire, EMS, police, trash, and other services—does not rise in step with the number of residents along that mile. That means local government revenues will rise faster than costs, allowing our cities, towns, and counties to provide more and higher quality services, and, at some point, to reduce local tax rates. We recently studied Grand Rapids, Mich., which stands to increase its revenue available for infrastructure spending by 70% a year with only modest tweaks to their current land use plans.

A Triangular Bargain

In the climate of today’s national politics, saying that a proposal would help the country overall doesn’t guarantee its success. There is another package of specific ideologically-attractive terms that can be built into this infrastructure deal to broaden its partisan support.

Let’s start with conservatives. Because of the scale of the historic pent-up demand for walkable communities—across red and blue states equally—the 20th Century subsidy formula can and should be reduced. Currently, funding for highways enjoys a different 80:20 ratio; 80 percent of the cost of a highway project is funded by Federal grants and the remainder comes as a state or local match. However, transit has been built using a different formula: 50:50. We propose that by equalizing the local match to 50 percent federal to 50 percent local and/or private, we will be introducing long-missing market discipline into infrastructure sector.

Second, to counterbalance the power of Department of Transportation bureaucrats and the State-level DoTs that broadly speaking are still stuck in the pork barrel thinking of the 20th Century, we propose that local authorities have direct access to apply for Federal funding in either category, for projects wholly within their geographic jurisdiction. This would mean small towns, city bureaus of transportation, and metropolitan planning organizations get more control of their destiny, organizations much more knowledgeable about local needs to than even the best career civil servants in often-distant state houses.

Understanding business’ specific interests, it’s possible to enlist their support to get this important, groundbreaking legislation passed. From participation in trillions of dollars of financing to the reduction in obesity-related and productivity losses to the increases in consumer spending that will come from higher levels of employment with higher-wage jobs—American businesses will get a serious boost from this new economic engine.

Two additional provisions can help both big and small business put their weight behind passage. To blunt some of the effects of the increase in corporate tax rates the Biden-Harris administration proposes to pay for the new spending, we propose offering small- and medium- sized businesses tax credit if they are willing to re-locate their operations (office, retail, manufacturing, warehousing) into walkable locations. It’s a sweetener that will have significant multiplier effects and a variant could provide a reduced rate of taxation on capital gains invested in select projects within these new corridors. As businesses relocate, they will bring both their employees and their customers onto those corridors as well, buying and renting the new housing units and riding the streetcars and light rail that the American Jobs Plan is funding.

Big business will also seek more assurances that we’re not just going to pendulum back to the status quo ante in four years. So to lock-in this new economic engine, Congress should ensure that freight moves over this new network even more efficiently than over highways. First, that means a similar approach of providing businesses with additional tax credits or accelerated depreciation for transitioning freight facilities from road to rail. The amount of capital spent on warehouses alone in the last few decades based on an assumption that the Federal government would continue to prioritize highway transport is enormous, and blunting the momentum of those sunk costs is critical. Second, because of the common-carrier nature of rail lines, the federal government should work with industry to create a sophisticated, digital, rail network management system so that passengers and freight can safely and efficiently get to where they want to go.

For progressives, we propose two elements in the trade. First, that state and/or local acceptance of any of the new funding, highway or transit, come with a decisive change in zoning ordinances to enable transit-oriented development to succeed. This generally entails sensible changes to allow for more density around transit stops and along their corridors and a corresponding reducing in parking space requirement. In addition, this could include local rules requiring minimal mixes of affordable housing and larger units for families with 3-5 bedrooms, “complete streets” provisions that provide shops and services within walkable neighborhoods, and the kinds of street grid improvements and parks that turn a transit stop into a safe, calm, and thriving neighborhood.

Second, in exchange for the introduction of more local and private financing as part of the deal, and regardless of whether a new federal minimum wage is not yet enacted, negotiators should include union-friendly “prevailing wage” provisions to all the new spending, to ensure that the hardworking people building this new American Dream have a secure place within it.

How (Part 2): Now, the Details

It’s one thing to negotiate a grand bargain, but it’s another to implement it successfully. Without including a number of new instructions for Federal, State, and Local departments of transportation, even the best deal can be stymied by institutional inertia and defensive incumbent businesses. The following four concepts need to be built into the deal so that the bureaucracy does not defeat the intent of the legislation:

Fix-it-first…and fix it right.

The Biden-Harris administration has already internalized the logic of “fix it first”—the notion that road funding should first go toward the massive backlog of maintenance and safety projects, and not build new miles of roads. But with this newly articulated end state—Chicago-level transit access for every city over 100,000—the rules around the road funding for “fix it first” must take into account a region’s plans for transit expansion. That will mean the bill should provide every MPO with some quick-release planning dollars to triage their roads into a prioritization scheme that avoids, say, complete rebuilding of an inner-city overpass when that old overpass will have to come down to reclaim the land for walkable communities built around transit.

Scale Up Better Funding Processes

In order for cities, counties, towns, special districts (business improvement districts, transit agencies, etc.), Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs), and state DOTs to be able to craft the transportation improvements they need, the federal Department of Transportation needs to shift its decision-making process. But we don’t need to re-invent the wheel. The Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) program, managed by the U.S. Department of Transportation is the place to start. TIGER (now called BUILD) stretched from 2010 to 2016, investing $6 billion using this bottom-up approach. It proved the possibility of getting ideas from the bottom up, not relying on top-down mandates. Basing the new decision process on the lessons of the TIGER program will keep the funding from getting stuck, or worse, being programmed into the last system’s priorities.

New Measures of Mobility

Every investment decision should be evaluated on the economic, social equity, public health and environmental impacts they will have on their communities and region. Unfortunately after seventy years of highway dominance, one measure, Level of Service, has come to rule all others. By scoring road projects on the basis of speed of traffic and level of congestion, this simplistic and destructive metric results in projects that blindly expand highways and primary roads to accommodate as many cars and trucks on them as possible, regardless of distance or time traveled. Instead, transportation planners and funders should use more modern methods, such as transportation access modeling, which calculate the ability of passengers to move efficiently from one point to another. Whatever the new measure system is, it must be truly mode neutral, while taking into account travel time, lifecycle cost, as well as social and environmental impacts.

Measure—and Invest In—Net Impact

There is a business principle that you can only manage what you measure. Our fights over infrastructure have been so protracted in part because we simply do not collect the data necessary to assess whether the promised results of a funded project actually came to pass. No business would operate so much in the blind and, especially as we increase private sector investment in transportation, we need to understand what’s working and what’s not. Place-based, bottom-up measurement should be used to determine the projected (future-looking) economic, social equity, public health and environmental impacts of transportation investments. And retrospective assessments (backward-looking) also must be done on a periodic basis to fine-tune our future investment decisions. But to really embrace this concept, DoT will need to incentivize regions to submit portfolios of interrelated projects that collectively reinforce each other and thereby reduce overall portfolio risk while improving total positive impact.

In Conclusion

It’s been seventy years since “we the people,” reset the American economic engine. It’s time. The economy built seventy years ago was unsustainable and inequitable, built before we knew about climate change and during an era that was still legally segregated.

With an historic pool of consumer demand aligned to a walkable American dream that itself addresses many of our greatest challenges, we truly have an opportunity to both do well and do good. But to get there, we have to be clear-eyed about what will secure the votes to pass not a watered-down bill, but an act that meets this moment with highest common denominator thinking. For that, we need to think out of the box.

This is the stuff that makes grand bargains. For a President and Vice President who were both former Senators, this is a most worthy test of their mettle. Americans will back bold action: the ideologies in Washington that protect the 80:20 funding formula or that consider transit anathema, they have no purchase here in the heartland. Americans want a new American Dream that’s built to last another seventy years so they can get on with improving their lives. That’s the high ground. That’s the radical center.

Abe and Ike, meet Joe and Kamala.