In tiny Ajo, Arizona, a low-slung white stucco pueblo-reminiscent house stands at the top of a hill, just across from where the massive open-pit New Cornelia Copper Mine was heading toward full-tilt production almost a century ago. The house, prominent in a quiet way, commands a view of Ajo and the desert below. Even from the outside, you can tell that the house was built to resist the sun and the heat of the summer months. If you turn west toward higher territory, you see a bright white cross at the top of another hill.

Anyone in Ajo can point out this Greenway Mansion, as the house is often still called, although it has since passed from the Greenway family to other hands. Most Ajo residents aren’t quite sure who owns it now; maybe someone from back east or up north, or maybe someone from somewhere else in Arizona. John C. Greenway, the house’s namesake, who came to Ajo to open the mine, was an imposing figure; a Rough Rider with Teddy Roosevelt, an engineer and mining executive, a candidate for the vice-presidential nomination at the 1924 Democratic National Convention, and a husband of Isabella Greenway. The cross was placed on the hill in his memory by his wife.

It was Isabella, with her string of last names, Isabella Selmes Ferguson Greenway King, who caught my attention. The headlines of Isabella Greenway’s life: a privileged and beautiful young woman who traveled on the edges of early 20th-century political and social power; close and dear though under-celebrated lifelong friend of Eleanor Roosevelt; twice a young widow of swashbuckling, pedigreed men; fearless entrepreneur and businesswoman; first woman elected to the House of Representatives from Arizona.

Where, I wondered, had she been all my life? As an impressionable girl, I was reading Nancy Drew when I should have been reading about Isabella Greenway. And later, how had I missed the connection during our American Futures adventures, when we visited tiny Eastport, Maine, and gazed over to Campobello Island, easily spotting the Roosevelts’ summer home, where Isabella had visited Eleanor.

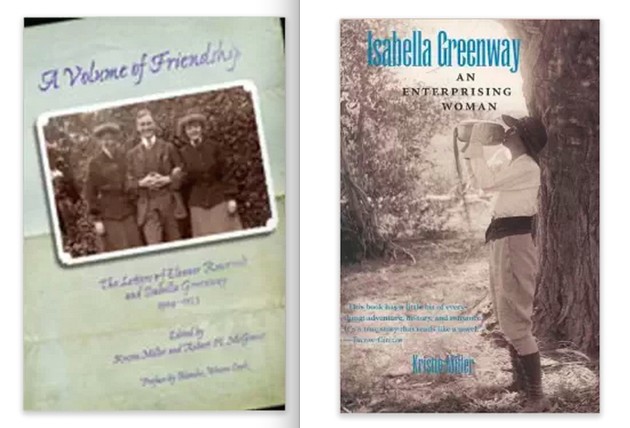

I finally stumbled upon Isabella through a wonderful biography stacked among the local-interest books at the Ajo Public Library. When I wanted it for my own, I found a copy in the bookstore annex of the Ajo Copper News. I devoured the book and its companion reading, a collection of nearly five decades of letters between Eleanor and Isabella.

I’m adding Isabella Greenway to the list of formidable American women whose stories I’ve come across in our travels. Here, greatly abbreviated, are three remarkable features of intrepid Isabella Greenway’s life.

Isabella’s Friendship with Eleanor

It was inevitable that they should meet. Teddy Roosevelt had befriended Isabella’s parents when they were young ranching neighbors of his in the remote Dakota Territory. Growing up, Isabella became a natural favorite of TR’s (as was TR’s orphaned niece, Eleanor) for her enthusiasms and charms, and she crisscrossed with many Roosevelts as she moved among relatives in the Midwest, New York, and Long Island, near Roosevelt’s beloved Sagamore Hill estate.

The girls met when Eleanor had returned from London for her obligatory presentation to New York society. They were quick and empathetic friends. Just a few years later, Eleanor chose Isabella as a bridesmaid (one of only two who weren’t officially family) at her wedding to Franklin. Within another year, 19-year-old Isabella married another family insider, Robert Ferguson, who had been a brave and dashing Rough Rider with TR at San Juan Hill and was 19 years her senior, or twice her age.

When Ferguson became ill with tuberculosis originally contracted in Cuba, he and Isabella, then 24, decided to move to New Mexico with their two small children for his health. The letter-writing between Eleanor and Isabella, which they had begun from nearly the time they met, became a dedicated exercise they sustained for nearly 50 years.

There was a lovingness to their writing. But in the context of the great variety of things they corresponded about, the intimacies seemed to be more stylistic flourishes of the era than an expression of exclusivity of their relationship.

During a particularly lonely time in New Mexico, as Kristie Miller and Robert McGinnis write in their book, Isabella writes with even more affection than usual.

November 9, 1915

The Homestead, Tyrone, N.M.

Eleanor darling, I’m with you—100 times a day—& don’t know why I don’t say so oftener. You are the one that almost drives me to the train eastbound. So hungry do I grow for a sight of you, a word with you…

Goodnight dear—I love you more every day.

Devotedly,

Isabella

After a busy year with children and without writing, Eleanor writes:

July 11, 1919

Dearest love to you Isabella dear,

Though I don’t write my feeling never change…

Devotedly ever,

Eleanor R.

Their letters also reflected the formalities of their class (they continued exchanging presents and writing “thank yous”) as well as acknowledgment and deep sympathies for the frequent and awful losses, anguishes, and betrayals that punctuated their lives. Isabella lost two husbands by the time she was 40; Franklin, well, we know about his polio and his affairs; there were illnesses; loss of parents, friends, children. The illnesses, especially, were reminders of the now primitive-seeming state of medicine, when people were simply destined to be “sickly.”

I was also struck by the honesty and bravery of their relationship. When FDR was running for a third term, Isabella, who had become a political force in her own right, publicly supported his opponent, the Republican newcomer Wendell Willkie. Isabella and Eleanor, who had remained personal friends and mutual public supporters during all this time, exchanged forthright letters about Isabella’s position and reassurances that their friendship would nonetheless survive.

Grit in Isabella’s Private Life

Hers was a life of dramatic adventure, disruption, engagement, and loss. For starters, Isabella’s parents suffered hard times with their ranching in the Dakotas. Her beloved mother, Patty, struggled with depression and alcoholism. Her dashing but impractical father, Tilden Selmes, died when Isabella was nine-years old. Isabella bounced between her relatives in Kentucky and Minnesota, often without her mother for long stretches. When Isabella was about 15, Patty, aspirational on behalf of her daughter, moved them both to live with more relatives in New York, to send Isabella to fancy schools and generally polish her up. The east coast swirl very soon became exciting, including visits to Teddy Roosevelt’s White House.

Then began the adult version of Isabella’s life. When she and Robert Ferguson decided to move to New Mexico for his health, it was life-changing. They chose a remote mountain-top homestead, living in tents and homeschooling children. Life was hard and lonely for about a decade. Outdoor life was challenging. She chaired the Women’s Land Army, which meant she toiled with other women in the fields while the men went to war. When Ferguson’s health further declined they moved to Santa Barbara, where he died soon after.

Soon thereafter she married John Greenway, who had been a Rough Rider with Ferguson and whom Isabella had gotten to know during the years of Ferguson’s illness. The Greenways lived in Ajo for barely two years, as it turned out. But it was long enough to build the house and be part of the inspired town plaza, school, hospital, and culture that drove the heart of the town and remains the anchor for its rehabilitation and reinvention today.

John Greenway died suddenly in New York following a routine surgery, and Isabella returned to Ajo on a train, suffering a miscarriage en route. She quickly gathered 3,000 people from across the country to Ajo, to help bury her husband. 3,000 people! Even today, getting to Ajo, a good 200 miles from Tucson or Phoenix, requires a substantial commitment. Many of the mourners must have come by train, on the long-since-gone railroad that Greenway had built.

Then Isabella charged on to build her own professional career.

Fearlessness In Isabella’s Public Life

After John Greenway died, Isabella lobbied hard to place a statue of him in Statuary Hall in the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., a statue sculpted by no less than Gutzon Borglum, who carved Mount Rushmore.

She became a force in Arizona politics. By 1928, she was elected to the Democratic National Committee. Four years later, she was rewarded for her effective lobbying on FDR’s behalf with the chance to second his nomination at the Democratic National Convention. In 1933, Arizona’s sole seat in the House of Representatives became vacant when the incumbent joined FDR’s cabinet. Isabella was elected to that seat with 73% of the vote. As a politician, she was loyal to her causes and her state, working for disabled veterans, the copper industry, and the underemployed in her state. She won WPA projects for Arizona. And yet, by 1940 (having voluntarily left Congress while still popular), she publicly supported Wendell Willkie over FDR for his third-term bid. Her strong personal friendship with Eleanor survived this difficult public moment.

Isabella seemed equally fearless as a businesswoman, again working around causes she believed in. She started a furniture business for disabled veterans, the Arizona Hut, as a way for them to earn an income, and then opened a hotel, the still-renowned Arizona Inn—some suggested this was because she needed a place to put all the furniture that the veterans made. She bought and operated a cattle ranch. She bought a small freight and passenger airline, Gilpin Airlines, which was started by a former-military driver of John Greenway.

When we took a break from our travels to touch home base in Washington, D.C., a few weeks ago, I had planned to go to the U.S. Capitol to see John Greenway’s statue.

Too late. In February this year, John Greenway was removed, sent back to Arizona, and replaced by a currently more famous son of the state, Barry Goldwater.