We took off west from Demopolis, Alabama, prepared for a lot of flying ahead on this last journey for The Atlantic’s American Futures project. (First two installments in the series, taking us from D.C. to Alabama, here and here. ) We passed over Meridian and Jackson, in Mississippi, just a ways south of Columbus, Starkville, and West Point, where we spent several reporting trips to the booming manufacturing center of the so-called Golden Triangle.

I have always looked forward to crossing the Mississippi River. We’ve done that in just about every state through which the mighty river flows, especially in the upper Midwest: Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois. There it would be today in the state of Mississippi, below us just around Vicksburg. I was worried about even getting a glimpse because of the low-overcast clouds, which we were flying above (on an “instrument flight plan” because we were expecting to have to land in cloudy conditions). We watched the navigation maps on the cockpit monitors, and just as we were about to cross, the clouds parted. Jim banked the plane so as to dip the wing on my right seat side, and I stole enough of a look to recognize the unmistakably mighty Mississippi.

We stopped for fuel in Minden, just shy of Shreveport, aiming for Dallas to install the software patch that we needed for weather readings. There’s always something, even in this little plane; it amazes me that the big boys fly around with as few mechanical and technological delays as they do.

By the time we were ready to take off from Dallas the next day, a cool drizzle had moved in, reminding us why we avoided winter during most of our flying in the last three years. For the next three hours after departure (again on an instrument plan), we were either in the thick cloud layer or just above it, barely seeing the vast stretches of west Texas below us or the sun above.

I think Jim enjoys the challenge of this kind of flying. He is always on top of the instruments, pushing buttons of one sort or another, checking gauges, and testing the redundant systems. For me, this opaque flying is unpleasant, sometimes even boring. I don’t like the absence of orientation. Most pilots, I’ve learned, have a zealous passion for flying. It’s something they can’t not do, and they don’t seem to mind the conditions. For the rest of us, well, I for one consider flights like these functional. The plane is getting me west.

The air traffic controllers were busy over west Texas. There is a lot of military airspace, and we could hear the calls from “Fighter 25” and “Fighter 26,” working with the air traffic controller (ATC). There were at least five medevac flights calling in that day, which seemed like a lot until you considered the long desolate stretches of road lying between sick or injured people and medical attention. In rural Ajo, Arizona, we knew that rural medical care meant that pregnant women often took precautions to drive the 200 miles to Phoenix or Tucson some weeks in advance of their delivery dates. The medevac flights always took priority, no questions asked.

Pilots requested vectoring to get to Amarillo, San Angelo, Dalhart, Alpine, El Paso. The names were exotic and evocative to me. When the ATC chatter died out, we switched to Sirius/XM radio, toggling among some of our favorites. Road Dog Trucking warned about winter road conditions over Omaha and St. Louis and impending ice storms. Rural Radio would offer local crop prices or advice on pest control, depending on when and where we were flying. There are entire stations dedicated to Willie Nelson, or Bruce Springsteen, or music of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. There is Coffee House music, jazz, and the often-irreverent Catholic guys on the Catholic Channel.

We ascended to 10,000 feet to cross the very southern remnants of the Rockies, the Guadalupe Mountains, on our way to Las Cruces. This reminded me of the tail end of the Great Wall that we climbed in Gansu province in China, where the crumbling remains became little but an obstacle for the farmers to work around in their fields. Finally, the cloud cover was dissipating.

Our little cabin isn’t pressurized; it’s legal to fly without oxygen up to 14,000 feet (after 30 minutes at 12,500 feet, the pilot has to use oxygen, of which we have small emergency-use bottles on board). But I felt myself involuntarily taking longer, deeper breaths. And I also checked the color of my fingernail beds for any tinge of blue, which signals oxygen deprivation. We were fine, of course.

We refueled in Las Cruces, looking for late afternoon lunch and settling on the beef jerky I always packed for such lean times. We decided to press on another hour or so to Tucson. The mountains deflated into undulating brown hills. There were flatlands with some volcanic outcroppings or long stretches of almost-surreal desert landscapes.

Sightings of such geology—volcanic or the colored striations of angular mountainsides—always make us feel very small and our moments on this earth fleeting. Not to wax too dramatic, but flying does that to your perspective.

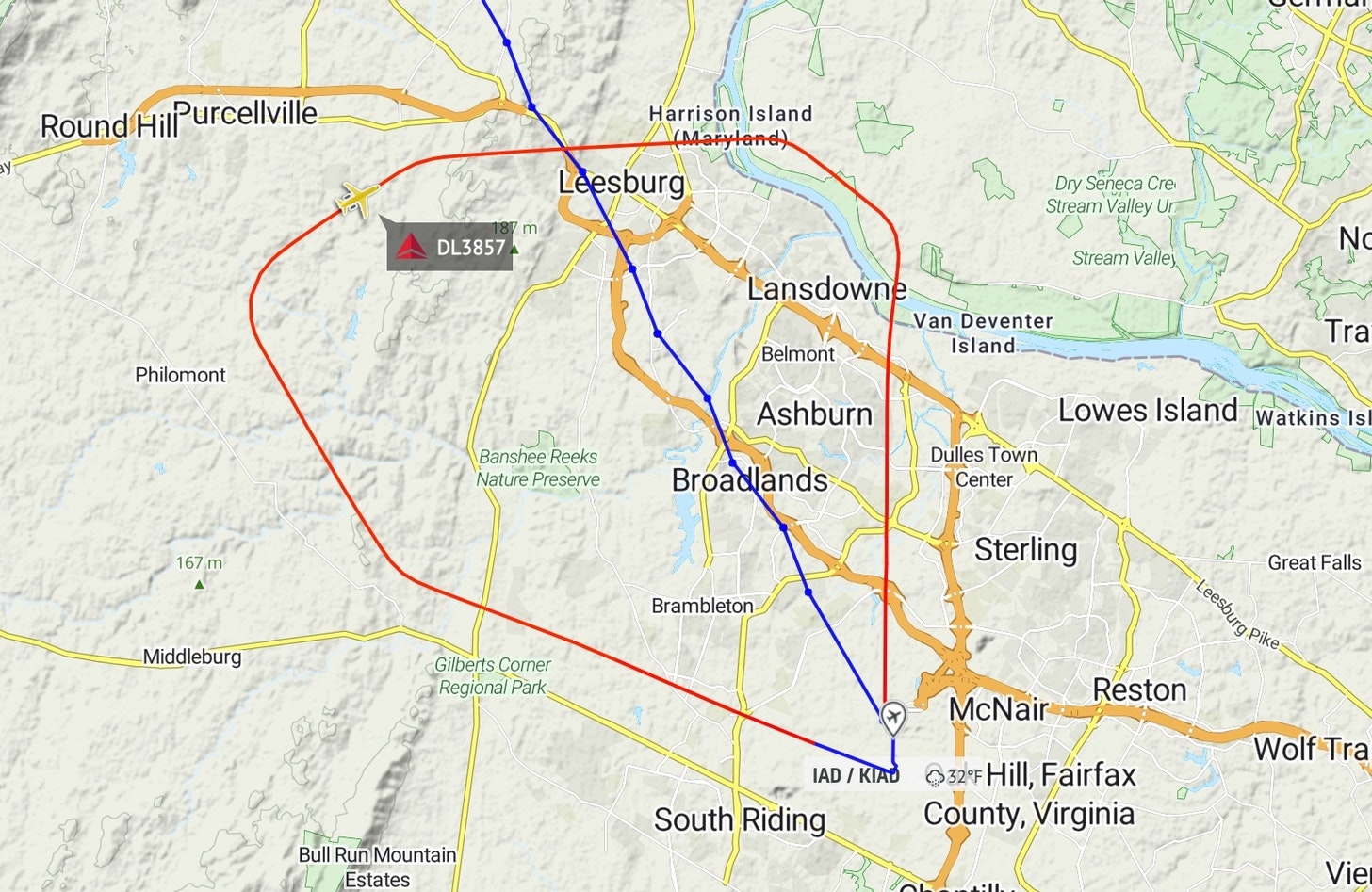

Finally, Tucson. Approaches for landing follow a U-shaped pattern. The goal is to land flying into the wind, which offers more control. Basically, you fly “downwind” along the side of the airfield, in the opposite of the direction in which you intend to land. (In this case, we were on a “right downwind” because we would be making a series of right-hand turns toward the airfield on our right.) Then you turn 90 degrees, called turning “base”, for a short hop perpendicular to the runway. Then you turn another 90 degrees for “final” and you’re home free.

As we were about to turn base, the winds suddenly shifted. Really suddenly. The Tucson Approach controller told Jim to loop around in exactly the opposite direction from what he was planning, and prepare to land on the same runway in the opposite direction. (For airplane buffs: we had been planning to land on with “right traffic” for Runway 11 Right. Suddenly the winds favored landing in the opposite direction, with left traffic for Runway 29 Left, which is the same strip of asphalt headed the opposite way.) Surprise!

It’s moments like these that I’m grateful for the professionalism of the ATCs, grateful for constant upkeep and training that Jim does as a pilot, and grateful that all the other pilots from those in the big commercial regional jets or the fancy little Citations or the humble single engine propeller planes like ours, are nearly always reliable, too.