But in looking at Pittsburgh’s impressive revival, it’s important to take note of the key role played over the last 30 years by the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, an organization that has managed one of the city’s most vivid transformations, turning a large part of downtown that had been overtaken by porn shops, strip joints, massage parlors, and sleazy bars into a lively, safe, and attractive district for cultural arts and entertainment.

Pittsburgh is not unique, of course, in looking to the arts as an economic catalyst for revitalizing a downtown and improving an urban area’s quality of life. Cities across the country, small and large, realize that a vibrant arts scene can attract people downtown and spur the opening of restaurants and other supportive amenities.

Let’s go back to the origins of this urban experiment. In 1984, McMahon tells me, “There was this group of really creative people—a band of dreamers, led by Jack Heinz [H.J. Heinz II]—who said, ‘We’re not going down for the count. We’re going to be transformative. Downtown is the core of our region, and we’re going to do something about it.'”

With the support and leadership of the Heinz Endowments, the Richard King Mellon Foundation, and the Benedum Foundation, that group of visionaries founded the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust as a non-profit organization with the goal of revitalizing the city. The Trust is an unusual 501(c)(3) that is partly an arts-promotion and management organization and partly a real-estate development and management organization, overseeing more than a million square feet of real estate.

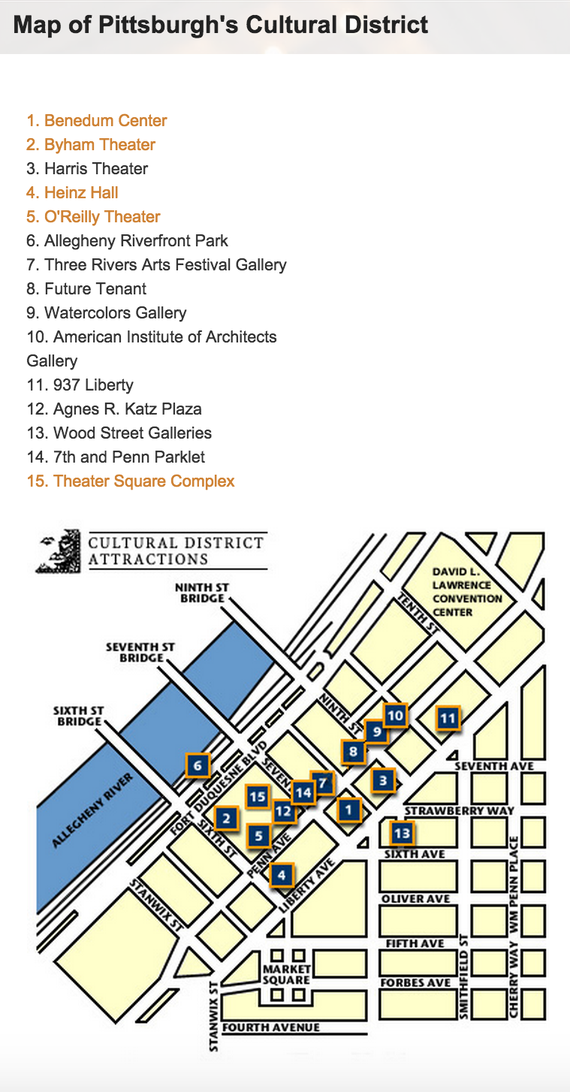

In the downtown “Golden Triangle” area, Pittsburgh had a number of grand old theaters and performance venues—spaces such as the Stanley Theater, a 2,800-seat venue, built in 1926, that is now called the Benedum Center for the Performing Arts and is home to traveling Broadway shows and Pittsburgh’s opera and ballet companies; and the 1,300-seat Byham Theater, built in 1903 as a vaudeville house. The initial thinking was that, at the very least, those old theaters ought to be restored for continuing use.

Years earlier, through Jack Heinz’s efforts, Loew’s Penn Theater, originally built in 1927, was saved from demolition, extensively renovated, and reopened in 1971 as Heinz Hall, having been repurposed for the Pittsburgh Symphony. That success helped form the vision for what was possible downtown and helped fuel the formation of the Cultural Trust. By the early 1980s Heinz Hall was crowded with performances by the symphony, the Pittsburgh Opera, and other performing-arts groups, so the need to renovate other theaters—especially the slightly larger Stanley/Benedum—was imperative to allow all the organizations to grow.

But the theaters were scattered in an area that was home to the city’s red-light district. The “aha moment” for the “band of dreamers” came, according to McMahon’s account, with their realization that in addition to renovating the theaters, they really needed to take on the goal of cleaning up the surrounding neighborhood. So, as they embarked on the process of saving the theaters, they also started buying up ancillary buildings and properties all around them.

McMahon notes two ways this venture could have gone wrong but that these visionaries somehow avoided. First, they could have simply built an iconic art center in a part of town that still had some life to it, hoping that alone would have been a sufficient catalyst for wider change, even when it almost surely wouldn’t have been. Or, even worse, they could have decided to clear-cut the urban center, razing everything in their target area and starting over. Instead, these folks decided to take a whole big area of downtown that was on the ropes and turn it around, restoring and reviving as much as they could.

What all of that adds up to, McMahon notes, is what makes Pittsburgh’s case so distinctive: “They decided to create a whole cultural district, not just a cultural center. And that’s a big distinction. Even today, there are many cities that have built—or are in the process of building—cultural centers. Think of Lincoln Center in New York or the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. But there aren’t many other cultural districts. Pittsburgh was in the forefront of this idea of curating and planning a whole big area.”

Those ambitious investments paid off, not only in terms of getting rid of all the noxious presences in the area and revitalizing beautiful old theaters, but also adding great value to those adjacent properties and buildings, an economic benefit the Trust is now reaping as it promotes adaptive reuse of a lot of those properties, including enticing developers to build housing downtown. According to McMahon, the residential population of downtown has tripled in the past 10 years.

A decade ago, the Trust put up the first large-scale high-rise apartment building to be constructed in downtown’s Golden Triangle in 38 years. “We did it,” McMahon says, “to demonstrate that ‘If you build it, they will come.’ People said, ‘Nobody wants to live downtown.’ Well, we’ve convinced them otherwise. From the day it opened, that building has been fully leased up.”

The area is lively and appealing. Ten years ago, a million people came into the cultural district over the course of a year. Now, the district is attracting twice that number annually to its multiple theaters, public-art installations, art galleries, and urban parks.

With obvious delight, McMahon told me of the Trust’s successful efforts to attract people to the art galleries in the District with its highly successful “Gallery Crawl”—a periodic event with festive street music, food, and drink—that attracts many thousands of people to simultaneous openings at the galleries. “It’s about experiencing the art,” McMahon says. “But it’s also about fun! It’s about experiencing community.”

This is a good place to note that, throughout our conversation, McMahon was eager to give all the credit for the cultural district’s successes to others—mostly to Jack Heinz and the other founders of the Trust, as well as to Carol Brown, who preceded McMahon as president and CEO from 1986 until 2000. His humility is admirable but misleading. While the Trust surely benefited from early, strong leadership, McMahon has now been at the helm for 13 years, is a beloved figure in the community, and is widely hailed as an exceptionally able leader, who has steered the Trust with vision, energy, and skill (see here, here and here).

As our conversation turned to programming, McMahon shared his concerns about audience development. “We all know that people are getting more and more distracted. People are busier. Interests and tastes change. So, you have to worry: Who is going to be filling up all these seats in 10 years?!”

“The Broadway-musicals world is growing like gangbusters,” he says, “Those shows always sell out.” So, the Trust will continue to program those kinds of “popular, large-scale entertainments that can only be in the kind of large-scale venues we operate.”

But because McMahon wants the Trust to stay “in the forefront of both following and leading its audiences,” he is determined to continue to program things like a modern-dance series, which requires substantial underwriting. “We do it because it’s part of what we do—provide art that people can’t get elsewhere. We believe in providing a very balanced approach to our artistic programming, making sure that there’s something for everyone.” That mindset also leads to the PCT’s efforts to promote small, innovative theater companies like Bricolage Production Company and the Pittsburgh Playwrights Theatre Company.

In short, Pittsburgh clearly has a winning formula for its cultural-arts scene and for using the arts as a spur to the city’s vitality. It’s all succeeding. But, as I noted near the start, there are elements to the Pittsburgh model—and keys to its success—that other cities cannot easily replicate.

By far the most important of these is what McMahon calls the “enabling” role of Pittsburgh’s legacy foundations—”our secret weapon”—that allows Pittsburgh to “be on a cultural par” with cities three or four times its size. With a wry smile, McMahon tells me, “We have a fair number of cities from around the world who come in here and ask how we do it. When I talk about the foundations, they get depressed.” The Heinz, Mellon, and Benedum philanthropies have made things possible for Pittsburgh that simply couldn’t happen elsewhere without that same infusion of financial resources.

With that in mind, I asked McMahon whether there are lessons other cities can take from the Pittsburgh experience. He noted that it’s possible to succeed without enormous resources. Expert advice and help are available from “various wonderful organizations.” For an example, McMahon pointed to ArtPlace America and its “creative placemaking” program, which provides resources along with expertise in best practices.

Finally, McMahon advises, it’s important to be authentic. “No matter what your aspirations are, do a little soul-searching first and make sure whatever you do is authentic to who you are and what you are as a community. Don’t try to duplicate what X, Y, or Z city has done. Figure out what you are, then think creatively about capitalizing on that.”

McMahon paused and looked around at the exposed-brick walls of the room we were meeting in. The Trust’s offices are in a modest, but nicely remodeled building. “We’re sitting in what used to be a massage parlor,” he said with a laugh. “Here in Pittsburgh, they could have torn down all these buildings, and that would have been a tragedy.”