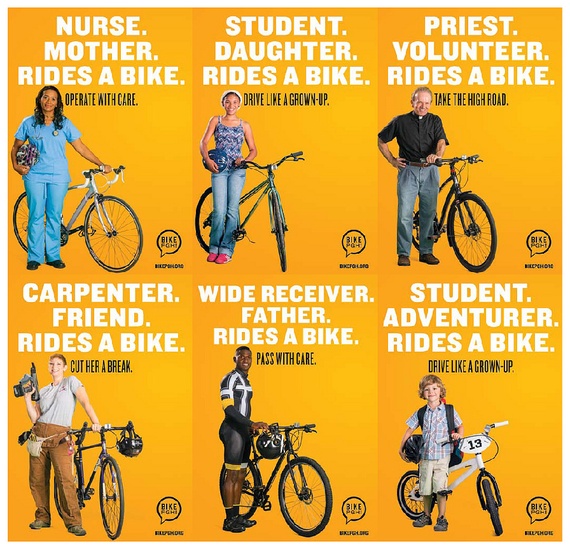

Becoming more bikeable: That seems to be a must for any self-respecting major American city these days. But what does it take to achieve that goal? Resources, of course—the funds to create the infrastructure for safe and comfortable bikeways. But the most important thing is political will. It takes real political leadership to overcome opposition to change.

Just ask people in Pittsburgh, which is making great progress on its goals to become more bikeable. It’s happening partly because of long-term, purposeful advocacy from organizations like BikePGH. But the most important factor in Pittsburgh’s success is the political leadership of Bill Peduto, the city’s mayor of only eleven months.

When I was in Pittsburgh reporting for the American Futures series about two weeks after the dedicated bikeway was put in, I spoke with Scott Bricker, the co-founder and Executive Director of BikePGH, the city’s premier advocacy organization for biking. Bricker told me that he had “never seen a public works project in Pittsburgh get put in place as fast as that one did.”

And Mayor Peduto has committed to extend it another 3.5 miles so that by the end of 2016, there will be five miles of protected bike lanes in place downtown. That’s real progress. While the city already has about 65 miles of painted or marked bicycle lanes on its streets, this is the city’s first protected lane. Bricker calls this separated bikeway “a big step forward” for Pittsburgh. Its creation came with the help of a small grant from a Colorado-based nonprofit advocacy group called PeopleForBikes.

According to that organization, one of the advantages of a very simple protected bikelane with collapsible plastic bollards, like the Penn Avenue bikeway, is that it’s easy to install and is flexible, so the construction phase can take place while the public-input process is still ongoing. Pittsburgh’s implementation of the Penn Avenue project proves, says PeopleForBikes, “that it’s possible for governments to move fast without neglecting public outreach. Instead of asking people to judge the unknown, the city’s leaders built something new and have proceeded to let the public vet the idea once it’s already on the ground.”

Mayor Peduto shares a position of steadfast leadership on this issue with Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald, also a strong advocate of better bikeways. In early September, Fitzgerald announced that two city bridges would be getting permanent bike lanes in the near future.

In fact, Peduto and Fitzgerald traveled to Denmark this past June, along with Scott Bricker of BikePGH and David Roger of the Hillman Foundation, to see Copenhagen’s biking infrastructure. Peduto and Fitzgerald already were strongly committed to making Pittsburgh more bikeable. Even so, Bricker told me, the visit to Copenhagen had a big impact on all of them.

“You can read about it or know about it intellectually, but it’s different to see it in person,” Bricker told me. “It’s amazing to see an already fully built-out system. There’s a network of bikeways that connects everywhere in the city. And because of that you get this network effect where some streets get 35,000 bicyclists a day, which is hard for us to imagine happening in the U.S. It just shows that when you invest heavily in connectivity, and safety, and comfort for biking, you see the rate of that activity skyrocket.”

Here are two videos, the first one on the “State of the Lanes” in Pittsburgh and the second one from STREETFILMS, in which Peduto reflects on his experience seeing the vibrant biking community of Copenhagen, and talks compellingly about why it’s so important to him to make Pittsburgh more bikeable and walkable. He makes clear his resolve to have Pittsburgh “leapfrog” over other cities in this element of urban livability: “We’re not going to settle at just playing catch-up. We want to catch up—and then go ahead.”

The Bike/Ped Coordinator’s job, a local reporter wrote a few years ago, is “to make pedaling or walking the city’s 89 neighborhoods, car-choked pinch-points, and steep slopes a little less of a thrill ride.” Bricker told me that in other cities, if this position exists at all, it often “sits vacant for years, so it’s a really good sign that Mayor Peduto prioritized this hire.”

Saunders’s portfolio will expand in the months ahead when another big element of Pittsburgh’s effort to build a more bikeable community will be rolling out. In the spring, the city’s Bike Share program will start, with 500 bicycles and 50 different stations. And the goal is to have this connect seamlessly over time with the plan to create more bikeways and a whole “bike-highway system” that will provide safe and comfortable bicycle-commuting routes for thousands of people who want to bike downtown to their jobs.

Bricker of BikePGH understands, as the mayor also surely does, the tensions between the advocates for more walkable, bikeable cities and people tied to the dominant culture of automobiles—between those who want faster change and those who find it threatening, inconvenient, or misguided. And he understands that bicycle-transportation projects often are mistaken as signs of gentrification. “That’s a concern,” he says. “But biking and walking happen to be the two most affordable transportation options out there. Cities are changing. And the question is: How do you create a city that helps make people’s lives better? We’re talking about quality of life and quality of place.”

Scott Bricker says of the strong desire for a bikeable, walkable city: “You don’t just have a special-interest group saying this. You see the desire for biking and walking and place-making coming out of all these community-development groups and neighborhood-based organizations. You have neighborhoods themselves saying, ‘we want bikeable, walkable places.’ ”