I am talking about the small, independent, start-up breweries and distilleries whose numbers have increased by the thousands in the past decade—but many of whose members are now just trying to hang on.

In previous installments, I reported on businesspeople from Massachusetts to Minnesota to Southern California who were trying to adapt to pandemic-era realities. Among their themes:

- The newest companies are the most vulnerable. Those that survive are usually drawing on at least a few years of market awareness, built-up savings, and civic support to get through these bleak times.

- Adaptability is everything. Start canning and selling beer you previously dispensed via taps. Move operations outdoors. Make hand sanitizer (although even that market has drastically changed.) Do whatever it takes.

- Embrace the “shift to quality.” As people are spending less time and money in bars and restaurants, some of them are “buying up” to higher-level food and drink to have at home.

- Recognize long-standing sources of friction. Antiquated distributorship laws, described here and here, had for years been a nuisance for small businesses. With the pandemic, they became a life-or-death threat. Shortages and soaring prices of aluminum cans, labels, and canning machinery suddenly were crucial to whether small businesses could last this collapse.

Now, two more brief reports, from different kinds of small businesses in different parts of the country. One is a small, relatively young taproom-based operation in Pensacola, Florida. The other is a longer-established independent brewery with wide distribution in California. Each underscores some of the previous principles and illustrates new ones.

Perfect Plain in Pensacola, Florida: Almost three years ago, the Perfect Plain brewing company opened in a still-reviving part of downtown Pensacola, the westernmost city on the Florida panhandle. The name came from a locally famous description that Rachel Jackson had given the region in 1821, when her husband, Andrew, was the incoming governor of Florida. “Pensacola is a perfect plain,” she wrote to a friend. “The town is immediately on the bay, the most beautiful water prospect I ever saw … There is something in it so exhilarating, so pure, so wholesome, it enlivens the whole system.”

The city has long had an economic bulwark in the nearby Naval Air Station, and of course its beach and resort areas, as well as a deliberately nurtured and increasingly popular arts-and-events scene. Its downtown has followed the retail, restaurant, and residential pattern of revitalization we have seen in many other cities. Part of that downtown growth was the opening of the Perfect Plain’s taproom, downtown on East Garden Street, in November 2017.

I visited Pensacola, to take part in its CivicCon public-discussion series, a few months after Perfect Plain opened. Naturally I made the taproom part of my inspection tour of the town (along with the stadium for the Blue Wahoos minor league baseball team, which has been put to creative use during the pandemic). I talked then, and have stayed in touch since, with D.C. Reeves, a Pensacola native and former sportswriter in his mid-30s. He co-founded Perfect Plain (with Reed Odeneal) in 2017, and has since written a how-to handbook for aspiring microbrewery entrepreneurs.

Over the next two-plus years, the business grew fast; Reeves hired more staff (17 people, from the original 8), and Perfect Plain leased more space for expansion. Pensacola was on the rise as a resort destination. Although the brewery’s only sales were (by choice) through its own taproom, rather than through retail or restaurant distribution, by early this year Perfect Plain had entered the top quartile of overall beer production in the state.

But what happens now, when the very elements of a downtown brewery’s success—crowds in the taproom, live events, drop-in traffic from tourists or ballgame crowds or shoppers strolling the downtown—are gone or diminished?

When I talked with Reeves last week, he repeated some themes I’ve heard and reported on elsewhere. For instance, he told me that his company was in better shape than some other, newer outlets, because it had nearly three years to build its brand and generate community support. And all-fronts scrambling, he said, was an expected part of the start-up path.

“There is this built-in creativity to the business,” he said. “If you have a brewery, or want to open a brewery, you know you’re going to have to claw and fight and create to keep a business alive.” He and his team ramped up sales of canned beer-to-go; they produced and sold hand sanitizer, the profits from which went directly to the staff. The company’s scrambling had been centered on trying to minimize layoffs. Perfect Plain received about $90,000 in PPP grants and devoted it all to staff salaries. Those funds expired in June. Since July, Reeves and Odeneal have reduced their own salaries to zero.

And, as we had heard elsewhere, Reeves underscored that the craft-brew business had always been volatile. The current crisis, coupled with an already impending plateau of craft-beer saturation, was weeding out any company without a sound business strategy—in addition to penalizing others that simply had not had enough time to establish their brands.

But he also mentioned a distinctive Florida aspect: the “magical hotdog,” or plate of food.

Florida’s handling of the COVID-19 threat has been, at best … well, you can fill in the adjective. One of its regulatory aspects was a bright-line distinction between “restaurants” and “bars.” In the closings-and-openings of businesses across the state, enterprises officially classified as restaurants were at first treated like bars, both of which were closed down. Then restaurants were given much more leeway to reopen while bars remained closed. Since restaurant owners were also desperately doing whatever they could to survive, the result was an additional challenge for businesses like Reeves’s.

“What we’ve seen is, in effect, restaurants becoming bars,” Reeves told me. “You can sit outside and have drinks all afternoon, but if you’ve got that plate of jalapeño poppers, it’s ‘safe'”—because you’re in a “restaurant.” The same drinks with the same spacing on a similar outdoor patio, minus the jalapeño poppers, would mean you were in a “bar,” which was supposed to be shut down. “The rules put a brewery like ours, with expansive square footage to space people out, in the same category as a boom-boom room in Miami,” Reeves said.

Inside the Perfect Plain taproom (Courtesy of Perfect Plain)

Inside the Perfect Plain taproom (Courtesy of Perfect Plain)Because their business plan was based solely on sales on their own premises, closing the taproom initially cut off their entire revenue stream. “But it was a different market when everyone was closed down”—that is, bars and restaurants alike. “We could capitalize on having an exclusive product and do the things breweries know how to do”—including to-go sales of canned beer. “We’ve been ready to wash cars, deliver on an ice-cream truck, do whatever it takes,” Reeves said. But when the restaurants were opened and the bars were not, revenues plunged once again. “It’s hard to convince someone to pick up a can of beer to go when they can sit on a restaurant patio and drink all day and night as if it’s a bar,” Reeves told me in an email.

What was the answer? The civics-course response was an open letter from Florida’s craft brewers to the governor, asking for comparable treatment to restaurants. Halsey Beshears, the secretary of the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation (which oversees brewery and liquor licenses), responded with a tour of small breweries around the state, including a stop in the Florida panhandle. He heard from Perfect Plain and its counterparts about strategies for reopening, and what to do in the case of another spike. After the trip, Reeves told me, “we felt heard by Halsey,” and new plans may be in store.

In the meantime, the scramble-for-survival answer was to convert their taproom into a “restaurant” as quickly as possible, a trend rapidly spreading statewide. (Here is a Pensacola News Journal report on the ways bars were rushing to obtain “restaurant” licenses.) “Hot dogs, hummus, chips and salsa—we’ve got it!” Reeves said. Just inviting a food truck wouldn’t qualify for a restaurant license. (Florida has since allowed it if the truck’s permanent address is the brewery/bar) But the Perfect Plain building had a sink and kitchen equipment in a back room. “We worked full bore for about seven days to get it all ready, and get our plan set for review..” Hotdogs, hummus — “We’ll do what it takes.”

Almanac in Alameda, California: Almanac’s story differs from that of Perfect Plain in several obvious ways. Almanac is nine years old, versus nearly three for Perfect Plain. From the start it has been based in the prospering and food-and-drink conscious San Francisco Bay area, rather than in a town of 50,000 close to the Florida-Alabama border. And comparatively little of its business has been made up of direct sales through its own taproom, compared with distribution through other outlets. (For the record: One of my sons, an Almanac customer in California, has invested in the company.)

But the sharpest difference is how Almanac has fared through the pandemic. While most food-and-beverage outlets are scrambling to make it week by week, Almanac just had its best quarter ever.

Why, and how? I asked Damian Fagan, a design specialist and longtime homebrew enthusiast who, with Jesse Friedman, co-founded Almanac in 2011. The name was explicitly based on the venerable Farmer’s Almanac, and was meant to signal the farm-to-table (or in this case, farm-to-tap) spirit of the company’s operations.

“The idea is to have ‘Northern California in a bottle,'” Fagan told me. “Farmers’ markets here are open 52 weeks a year. There is always a cornucopia of delicious agricultural offerings we can use.” Fagan pointed out that the farm-to-table ethos had made restaurants proud of describing where their tomatoes were grown and how chickens or cattle had been raised. “Beer is 100 percent an agricultural product, but people weren’t paying attention to it in that way.”

In Almanac’s first few years of operation, before it had its own brewery, it specialized in “sours” and fruit-based beers, made under contract by local brewers. “Given where we are geographically, we have access to fruit year round.” Sours, which are aged in oaken wine barrels, now constitute about 30 percent of the company’s business. At one point it had a taproom in San Francisco, which has closed. Shortly before the pandemic it opened a sizable brewery and taproom in a former aircraft hangar near the former Alameda Naval Air Station, in the East Bay.

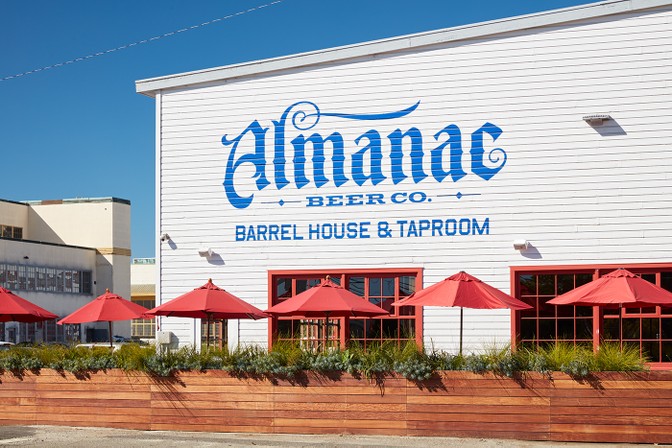

Almanac’s brewery and taphouse in Alameda, California, across the Bay from San Francisco (Courtesy of Almanac Beer)

“When the first shelter-in-place order [for California] was delivered, in mid-March, we panicked, like most people,” Fagan told me. “We had to shutter our tap room, which had become a big part of our business.” The phone started ringing—with calls from wholesalers and other distributors canceling their orders, or greatly reducing their scale.

“We wondered, is the sky falling?” Fagan said. The key to survival, he told me, was “to be nimble and adaptive.” Every business would use those words, but Fagan laid out what that meant, specifically, for his company.

“The first thing we did, within 72 hours, was to spin up an online beer store—a direct-to-consumer channel that we had not had before.” People anywhere in California can now order their beer online, for delivery to their homes. Almanac pushed online sales hard in its social-media outlets. Business through this new channel grew rapidly, and according to Fagan “went a very long way in filling the giant hole caused by closing the tap room.”

Almanac also quickly ramped up to-go sales of canned beer, from its Alameda brewery. Last year Almanac had invested in its own canning line; this meant it could avoid some of the problems other breweries encountered in trying to shift rapidly to takeaway sales. Recently I described how the Bent Paddle brewery, in Duluth, Minnesota, had made tough COVID-era safety standards part of its brand. Almanac took a similar approach. It had customers stand in line; it set up contactless pick-up; “we really dialed in on ways for people to feel safe,” Fagan said. “The irony is, when we combine to-go sales with the online store, we’re actually generating more revenue through our taproom with it being closed, than when it was open.” Almanac’s overall revenues for the first half of this year are about 10 percent higher than for last year—even with the near-disappearance of its taproom and restaurant sales.

Almanac has one other enormous advantage: Just weeks before the pandemic, its distributor made a deal with Safeway, which means its beers will be carried in some 170 Safeway stores in Northern California, along with some other retail outlets. Last month I quoted Jim Koch, of Sam Adams in Boston, on the make-or-break, life-or-death power that distributors have over many start-ups in this industry. Fagan said that Almanac, which had had difficult distributor relationships in the past, was now on the good side of that divide—”which allowed us to get this massive placement all at once.”

Sales through distributors now account for most of Almanac’s revenue. And in these stores, the company is now benefiting from the same “flight to quality”/”trading up” process mentioned before. “Instead of buying a four-pack of beer in the store, they may buy a case,” Fagan said—and of fancier products, like his. “People are buying in higher volumes, and drinking at home more.” The public-health aspects of this part of the pandemic are still to be understood. As a business trend, it is keeping some small companies alive.

Are these the biggest business and civic stories of America’s current disastrous dislocations? Of course they are not. But the rise of small, locally minded restaurants, coffee shops, bars, breweries, and other gathering places has been an important element in many cities’ growth in the past decade. Whether, and how, small businesses like these survive is important too.