Here’s a difference between the world of national politics and that of public problem-solving at the local and regional levels. Four or five years ago, I would have had no idea of this. Now I notice it practically every day.

In national politics, terms like partnership or collaboration are hard to utter with a straight face, or a non-sinking heart. At best, they can seem boring or (damning with faint praise) “worthy.” At worst, they seem like euphemisms for sweetheart deals or favor-trading.

In Washington I can feel the attention draining from the room whenever someone mentions “public-private partnerships”—or if Deb and I discuss some new cooperative project we’ve seen for advanced-manufacturing training in the South, or the reuse of abandoned buildings in the Midwest. The narcotizing effect is like that of the term infrastructure, back before “Infrastructure Week” became a bitterly joked-about term in Washington.

Yet in so many communities we’ve visited, everything about these collaborative efforts—finding the partners, dividing the labor, sharing the blame and credit, sustaining the relationship—has seemed not simply important but actually interesting.

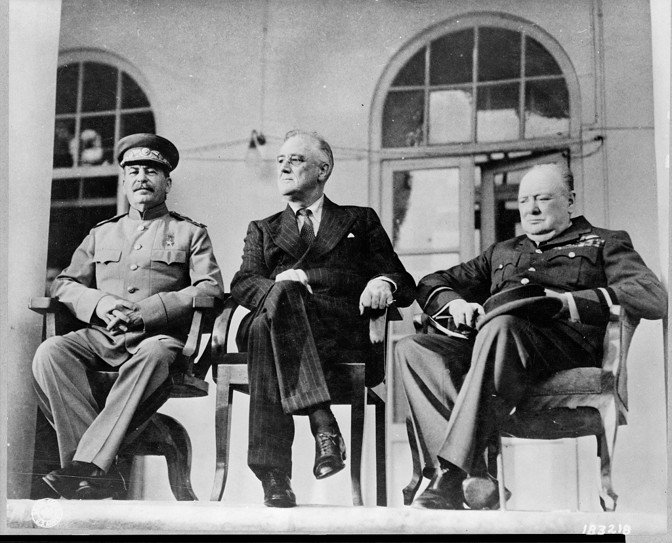

Consider this analogy: Anyone studying World War II knows that part of the story is the titanic drama of the battlefield. But another important part is the elaborate backstairs strategy of collaboration and coalition building. This involved: how Churchill dealt with FDR, how both of them dealt with Stalin, how the U.S. government worked with private industrialists to turn Depression-racked America into the “arsenal of democracy,” how Eisenhower and Montgomery and Patton and MacArthur worked with and against one another, and so on.

Similarly: The movie Lincoln and the book Team of Rivals were built on the drama of Lincoln holding a political coalition together so that Union forces could advance on the battlefield.

Today’s local-level partnerships obviously lack the world-historical immediacy of these wartime struggles. But the link between process and result is similar: people paying attention to the mechanics of how they work together, to increase the chance of reaching their goal. And the stakes can be very high: reducing the human toll of opioids or homelessness; expanding opportunities for people the modern economy has left behind; improving schools and policing practices; and on down the list.

Let’s take this back to Mississippi. This post is a an update on a project in the Golden Triangle of the state—the ambitiously industrializing northeastern region including Columbus, West Point, and Starkville—which exemplifies a commitment to collaboration that other regions could usefully study.

The physical symbol of the collaborative effort there is a new building that is opening this summer, in the industrial zone adjoining the Golden Triangle Regional Airport. The official name for the structure, which we saw in nearly completed form on a visit to Mississippi earlier this month, is the Center for Manufacturing Technology Excellence, or CMTE, 2.0. It is informally known as the “Communiversity,” and the name suggests the scale of its ambition. (For background on ambitions for the Communiversity back in 2014, see this report. For more on the highly creative community college from which it arose, see this.)

The term communiversity—a university, in a community—is familiar in higher education. But generally it refers to community-enrichment or -engagement efforts, as opposed to formal degree-granting programs. For instance, the communiversity at the University of Missouri at Kansas City was founded on the belief “that a community is strengthened when its members have avenues through which they can share their skills and ideas with others.” It offers some 850 noncredit, volunteer-taught courses. The one at the University of Cincinnatihas a similar approach. Princeton University and the City of Princeton are sponsors of a Communiversity ArtsFest there.

The Mississippi Communiversity is something different. It is a new physical home for a program that has been gaining momentum over the past decade, and that offers academically structured, industrially aligned for-credit classes. Its name reflects the simultaneous involvement of all these groups in organizing it, funding it, and now guiding its operations:

Together, these organizations provided funding for the $42.5 million center. (The money came mainly from state bonds approved by the Mississippi legislature, for about $18 million; commitments from the three counties, totaling $13.5 million; and support from the federal Appalachian Regional Commission, for $10.5 million.)

- A community college, East Mississippi Community College (EMCC), which is in charge of most of the instruction

- A research university, Mississippi State, based in Starkville

- High schools in the area

- The Mississippi state government

- The governments of three counties: Clay, Lowndes, and Oktibbeha

- The federal government, mainly through the Appalachian Regional Commission

- Many of the private businesses with factories in the area, starting with the truck-engine maker Paccar

- A regional-development organization called the Golden Triangle Development Link

- Local individuals in the area

The major manufacturers that have come to the area have played a role in various forms, including contracting with EMCC to train potential employees. The EMCC vice president for workforce and community development, Raj Shaunak, told me this week that over the past 15 years, EMCC has trained about 25,000 people—”and about 12,000 of them are currently employed in advanced manufacturing in the Golden Triangle area.” (For instance: The local advanced-technology steelworks run by Steel Dynamics employs about 750 people, according to Shaunak. A new Yokohama tire factory employs about 650.) These companies “are our partners in every sense,” Shaunak said.

Shaunak also singled out the role of a former Mississippi State president, Malcolm Portera, in catalyzing the successful cooperative effort in the area. Portera had been the head of the University of Alabama when the Tuscaloosa area attracted a new auto factory from BMW and an electronics factory from JVC. “When he came to Mississippi, he worked with everyone—state, local, federal—to showcase our local capabilities,” Shaunak said. “And he was visionary in saying we needed to build the original Center for Manufacturing Technology Excellence at EMCC. When manufacturing was declining, in the U.S. and in Mississippi, he said, ‘We can make it in America again.'” To me, the part of this story worth underlining is the head of a research university going out of his way to boost a community college.

What will happen room by room within the Communiversity will be familiar to those who have seen career-technical training sites around the country, or advanced-manufacturing start-up centers. (For those who haven’t been to such places, here are two reports from Louisville a few years ago that give some idea, and another from San Bernardino.) In short: Students at different stages of life are trained both in specific technical skills that can lead to immediate employment and in the longer-term “learning how to learn” skills that prepare them to adjust more easily to the jobs in demand 10 or 20 years from now.

A helicopter chassis, like the one above, will prepare students for work at the adjoining Airbus helicopter factory, or for aerospace-related jobs elsewhere. Ranks of advanced-machine tools, like the ones shown below, prepare students for advanced-manufacturing jobs.

My point for now is not the details of what the Communiversity’s first class of students and entrepreneurs will be doing when it starts working there this summer. It is instead about the breadth of the collaborative effort that makes this institution possible—and the implications of programs like this.

“I think many of us are worried that the American economy is doing half of its job,” Jan Rivkin, of the Harvard Business School, said after an HBS team visited the Communiversity site in the fall of 2017. He added:

“[The economy] is benefitting large companies and those who work for and invest in them, but it is not supporting working middle-class Americans. Rural communities are really struggling.

Yet here in the Golden Triangle, we see something very different going on: a community that is coming together to create broadly shared prosperity and great manufacturing jobs. We came here to learn. We came here to see what is going on that is special, and to figure out what we might apply to other settings in other communities.”

Might this all sound merely “worthy”? I give you the closing thoughts of Shaunak. “This is a way we can give people in a distressed area new family-sustaining opportunities,” he told me this week. “This is a way to help them realize their American dream.”

A mural in the about-to-be-opened Communiversity, earlier this month (James Fallows / The Atlantic)