This is the story of a man, and a region, and of the tradeoffs that go into the modern movement of industries. What did it take to bring an advanced-tech steel mill, a helicopter factory, a drone plant, and a major new tire works to a corner of the country where the unemployment rate is very high and many educational and sociological indicators are very low? And how much better off is the region for the arrival of these new enterprises? What did it give up, and what did it gain?

The region in question is part of the so-called “Black Prairie” of Mississippi and Alabama. That name refers to its soil type, as shown by the sweep of this map from the Mississippi Entomological Museum at Mississippi State University (which is in the region).

The background on our story starts here, with a roundup of some of the industries that have come to the Golden Triangle. It continues here, on the near-impossibility of untangling the influences of history, international economic trends, institutional and corporate culture, and individual mistakes or insights in understanding why things “succeed” or “fail” in a given area. It continues here, about the particular burden of race in explaining American events in general and Mississippi developments in particular. It is complemented here and here, with reports by Deb Fallows on the ambitious educational efforts underway at a public school in the Golden Triangle. And it will continue this afternoon in a broadcast version on Marketplace and later with at least one more installment by me, about Mississippi’s version of “career technical” education.

You’ve heard talk like this from any number of football coaches, and Higgins’s talk about his region’s prospect is very much that of a coach. Two examples, of many possibilities:

• On what he thought when he considered moving to the Golden Triangle from Arkansas, a dozen years ago:

“When the headhunter called and said I want you to look at a position in Mississippi, I said you gotta be kidding me! I hear ‘Mississippi,’ and I hear poverty, despair, no future, and no hope for a future.

“Then we drove through here, the azaleas were in boom; it was pretty. My wife said we should at least look the place over. We looked at what God gave ’em, and what they were doing with it. And I said, There’s no reason in the world these folks aren’t winning! But they’re not.”

Within “they’re not” was the whole range of local economic woes, from a starting point of low income and high unemployment, to a recent wave of factory closures among the low-tech, low-wage small firms that have moved to the South from the Depression era onward.

Higgins went back to the headhunter. “I said, here’s what I want: Audited financial statements, budgets, all this kind of stuff. I spent weeks just looking at stuff. Came to conclusion, these guys should be hitting home runs, but they’re not even getting to the plate. That’s an opportunity.” So he signed on.

• On what has happened since then, Higgins showed us a very detailed chart of all the industries that have included the Golden Triangle in their site selection during his time here, the number that went ahead, what that meant in terms of capital investment and tax revenues, and what it’s meant in jobs. To put it in perspective:

“If you take it strictly on investment, deals we won versus deals we lost, we’re batting .442! And some of those deals we lost are ones we said, go away, we’re not interested. But now, in jobs, we’re batting .241. So how good are we, really? Two-forty-one is maybe better than most, but it won’t get you into the hall of fame, not unless you can play second base like a champ. But .442 will get you into the Hall!” And on to an argument about why the average had to go up.

* * *

The Golden Triangle’s first big win was its certification as a TVA “Megasite” ten years ago. The Megasite system was a way for TVA to speed investment within its region by pre-clearing certain sites as being project-ready. They had the infrastructure, they had the permits, they had enough contiguous land, and everything else. As a Federal Reserve report described them:

The Tennessee Valley Authority coined the term in 2004 for sites in the TVA region that could be deemed worthy of large-scale development—1,000 acres in size, environmentally clean, and accessible to transportation and utilities, among other criteria.

For more about the Megasite program, you can see this and this from the TVA; for more about what it meant to the Golden Triangle, you can see this, from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. For instance, the headline of the Fed Reserve assessment is, “Megasites Spur Big Turnaround for Mississippi Region.”

The point for now is that Higgins and his colleagues at the “Link” development organization for the Golden Triangle threw themselves all-in to the competition to be awarded Megasite status. As he put it:

“The TVA was tired of every beanfield, cotton field, corn field in anytown USA saying, ‘We’re going to have the next Toyota-Nissan-Mercedes plant!’ So they hired a prominent national consultant to design the criteria for certification.

“Everybody showed up. The could be’s, the wannabes, the never-were’s, and thought-they-were’s, they all showed up.” All the candidate regions were asked to provide simulations of how they would handle major new investments, and to provide specs on every economic, infrastructure, labor-market, and environmental consequence of economic growth.

“They had a two-foot-high book of specs,” Higgins said. “We worked 12 hours a day, six days a week. Optioning the sites, doing the soil borings, everything.” To cut to the conclusion, ten years ago this August the TVA certified its first two Megasites. One was Hopkinsville, Kentucky, and the other was near the Golden Triangle airport in Columbus.

“The worm turned then,” Higgins told me. “That TVA decision was the inciting incident that changed this community forever. I’m serious. Before that, I’m working little projects. I’m working a sweet potato plant here, and a small, small automotive plant there. That was it. To be honest, when I took this job I thought I’ll hit a couple of singles, maybe a double, and then I’ll get a bigger better job somewhere else.

Soon after that, Higgins and his team got their first big commitment, with the $600+ million steel mill from SeverCorr, now called Severstal. Then they began applications for a second Megasite, which also succeeded. (The TVA has certified only eight in all, including the two in Columbus.) Then on through the list of other successful industrial recruitments, which in all have brought some $5 billion in total investment, and something like 5,600 new jobs, to an area where the unemployment rate, even with this new work, is still around 15 percent.

* * *

What has it cost, and what has it brought? I can’t claim to offer the full reckoning, but here is a summary, for follow-up in another installment.

• It’s not just money. The latest big investment news for the region is from Yokohama Tire, which is building a $300 million new plant near West Point, the most depressed part of the Golden Triangle area. It will employ 500 people when it opens next year, toward a planned total of 2,000.

As part of the courtship process, Higgins’s group arranged a site visit by the Yokohama corporate high command: helicopter tours of the area; green tea and hot, moist towels to refresh the visitors at each stop; galoshes to protect their shoes from the Black Prairie mud after a rainstorm.

During the aerial tour, Higgins took Yokohama’s chairman over the ruins of what had been for nearly a century the economic foundation of West Point. This was a meat packing plant, locally owned for decades by the Bryan family and then taken over by the firm that eventually closed it, Sara Lee. When it shut down it put fully a tenth of the city’s population out of work.

“I told the chairman [of Yokohama] that this was an area that placed a lot of stress on long-term relationships,” Higgins told me. “People worked for Bryan for generations. When that plant left, it tore the heart out of the whole community. I said, you can be the phoenix rising up, for the next generations.”

Hokey, yes. But Higgins said that the helicopter then did several circles around the plant, while the chairman stared down at the devastation. “He looked over at me, and nodded,” Higgins said. “I told the pilot, We can go now.” (Below, a Google Earth screenshot of the now-being-demolished remains of Bryan/Sara Lee.)

• But it’s largely money. Higgins says that the area doesn’t offer, and the TVA and EPA won’t condone, any waivers from environmental standards. And with the obvious exception of the flame-belching Severstal mill, the industries that are coming are relatively high-tech and clean.

What it does offer is substantial state and county subsidy for infrastructure and construction costs, and tax breaks. For instance, here is the Federal Reserve’s summary of what went into Severstal:

From the state, the company got a $25 million grant and $10 million loan for infrastructure plus a bunch of tax credits and breaks on sales taxes and other state taxes. The county contributed the land, a $5 million infrastructure grant and a cut of about 40 percent on real estate taxes. Together, the incentives were worth about $100 million.

The PACCAR plant, which makes engines for one-tenth of the long-haul trucks you see on American roads, got similar incentives totaling about $40 million.

Joe Max Higgins has made the “incentives more than pay for themselves!” argument so often, and so publicly, in such detail, for so many years that I assume it would have been debunked if it was hyped or untrue. “Part of the ‘Northern narrative’ on what we’re doing here is that we’re just buying industries,” he told me. “That might work if you were talking about a company that is not very sophisticated and doesn’t have a lot of resources. But your Nissans and your Toyotas and your Airbus? You think they’re going to sacrifice their business for some little tax deal? That’s bullshit.”

Who is being helped? The full answer is beyond my ken. Here are two things I could observe.

• The biggest industrial employers, Severstal and PACCAR, say the racial balance of their employees is “representative of the region.” The region is slightly more black than white; on the visits I made—two to the steel mill, one to the engine factory—the workforce appeared slightly more white than black, but slightly rather than heavily. Certainly it was closer to being racially diverse in the fashion of a military unit, than being overwhelmingly white in the fashion of many corporations or, especially, high tech firms. This question is so consequential that I’ll return to it, in talking about the role Eastern Mississippi Community College is playing in preparing underskilled local people of all races for forthcoming jobs at the Yokohama works.

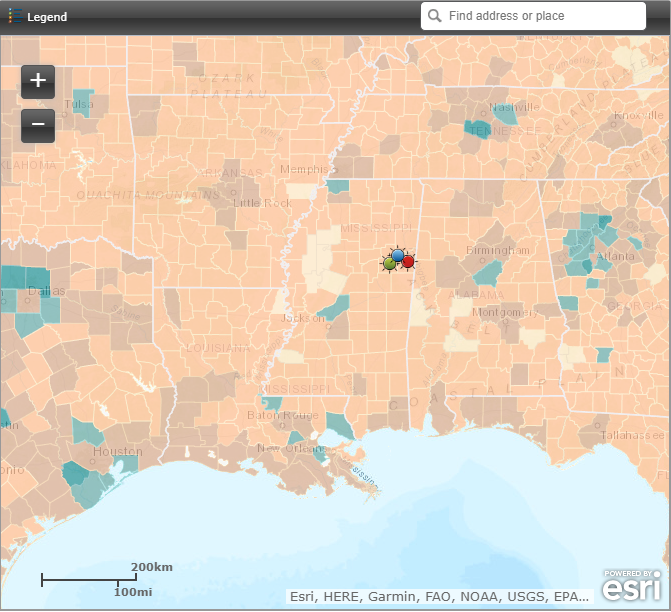

• The median income in these areas ranges from slightly below to very far below the national level. As mentioned earlier, the median U.S. household income is around $50,000 per year. It’s barely half that in much of West Point. Here’s a map showing income levels.

He mentioned a conversation he’d had with the mayor of a small town in Tennessee. “I’ll never forget when he told me, I can’t wait for the blue jeans plant to close in town!’ You never hear a politician say that. He said, ‘We got to get those ladies to community college and get their skills up. I can’t run my town on minimum wage.’ I thought that was the deepest thing I ever heard.”

* * *

There are more ramifications to the saga, but these suffice for now. Let me know your major complaints and questions and I will try to address them in upcoming installments. Next up from Deb Fallows: the surprising story of the Palmer Home for Children, in Columbus.