I swelled with pride at a report on public radio recently that my hometown of Washington has more public swimming pools per capita than any other city in the country. Current count is 29 public pools, said the radio; 30 said The Washington Post.

We wrote about some of the sports venues at the collegiate summer baseball league games in Duluth, Minnesota, and Bend, Oregon, where, by the way, resident families who generously host the college players in their homes for the summer were present and cheering. We wrote about the local gymnastics club in Allentown, Pennsylvania, where 200 town volunteers showed up on a Thanksgiving weekend to help complete their new world-class training facility. And then there are the libraries—in Oregon, West Virginia, Ohio, California, and many more, where the focus of the library programs speak to the critical needs of town, whether it is ready-for-kindergarten programs, or citizenship courses, or accommodating senior citizens, or staffed-up help with job searches.

In Rapid City, South Dakota, when I scurried in for the last 45 minutes of the open hours at the gleaming new Y, the woman at the desk said I couldn’t get my money’s worth with that little time, and she’d catch me on the next visit. I swam as fast as I could for as long as I had, and when I left, she asked if I had enjoyed my swim. I returned the next day for more.

In Burlington, Vermont, the old pool in the old building’s old basement was empty except for me and improbably, a very big and strong African-American 20-something swimmer, who seemed to me to be training seriously. In Holland, Michigan, a town founded by Dutch Calvinists which is now nearly 25 percent Hispanic, the pool was filled with the Hispanic kids and families, whom we had so far only seen in the Mexican food stores and restaurants. One thing I could be sure of at my Y visits was that I would rub shoulders with people whom I would not otherwise naturally mingle with in town.

In Columbus, Mississippi, there were a few octogenarians paddling in the overheated pool. Only in Mississippi did I find a reminder that this place was in fact the Young Men’s Christian Association; a big bowl at the reception desk held what I first mistook for candy; the contents were actually tiny papers, rolled into scrolls and each typewritten with a proverb.

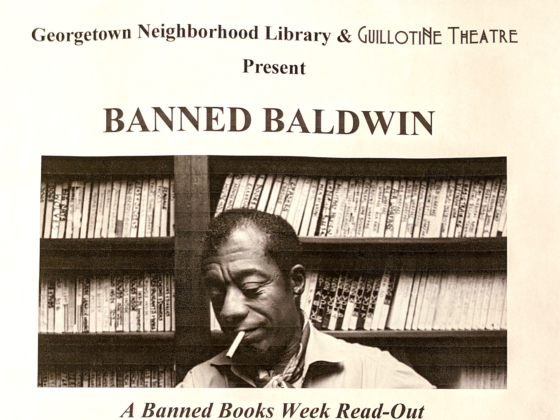

YMCA pool in Redlands, California (Redlands YMCA)

YMCA pool in Redlands, California (Redlands YMCA)The YMCA I knew best was in Redlands, California, where we were based this past winter for our west-coast travels, and where I had an actual membership. The Y is famous for its annual circus production, which I wrote about here. It serves as an anchor of the community, forging partnerships with the schools, the community hospital, and others. But it was an unofficial—and unheralded—role of the Y that struck me most.

There was a woman I saw who “lived” at the Y during a good chunk of every midday I swam there. She arranged her overstuffed plastic bags along the locker room counter. She showered long and hot, and rested often on a comfortable chair. Her legs were red and swollen, and did not look good at all. I asked about her once, wondering about her story. The staff told me quietly that oh, yes, they knew about her. “She doesn’t seem to cause anyone problems,” an incomplete but true answer, which bespeaks the generosity of the town.

In other towns, I went to the pools run by the cities, like my own in Washington, D.C.

In Sioux Falls, I chose one in a leafy residential part of town. It was filled with kids, their bikes propped against the chain-link fences, whiling away their afternoons until it was time to ride home for dinner. So many people in Sioux Falls, including the teenagers we met, described their life there as “safe” and “easy.” This is an example of what they meant.

In the heart of Greenville, South Carolina, nestled between the gentrified Main Street area on one side and a challenged urban neighborhood on the other is the Salvation Army Ray and Joan Kroc Center, where all of Greenville seemed to show up. There are sports courts, a childcare room, a soccer field, tennis courts, gyms, a boys and girls club, pools, and at the end of building, a chapel. The complex abuts the A.J. Whittenberg Elementary School of Engineering, whose students regularly walk the few hundred yards to swim in the pool.

In tiny Winters, California, the Bobbie Greenwood pool is right next to the public library. Bobbie Greenwood, a living legend of Winters who settled there as a young woman, built the pool out of her love of swimming and for all the Winters children to enjoy. I swam there, for a rather embarrassing fee of $1.00 (although I did have to change in the restroom and dry off with paper towels), as young kids darted back and forth between the library and the pool.

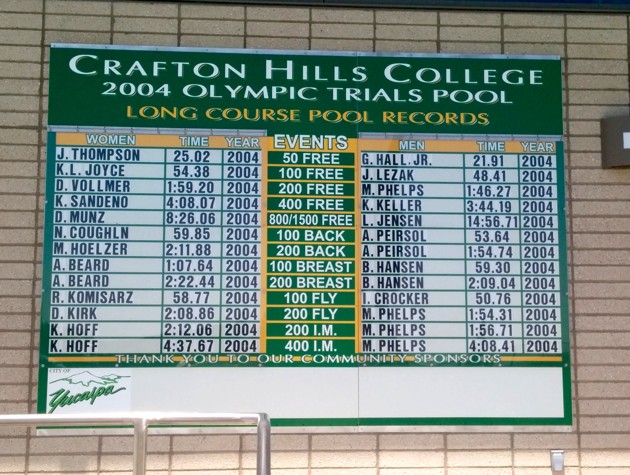

Pool-record board at the Craft Hills Community College in Redlands, California (Deborah Fallows)

I swam in many more places, too: the 50-meter pool of Crafton Hills Community College, set in the hills above Redlands and scene of the 2008 Olympic trials. On the record board, inspiring even those without competitive dreams, are the names of M. Phelps and G. Hall, Jr., A. Beard, and others.

And then there was swimming not in a pool but right in the chilly Snake River in Clarkston, Washington, in the heart of Lewis and Clark country, just upstream of a park Maia Lin designed one of her series of “Confluence Project” installations in honor of the Lewis and Clark expedition. And the eastern shore of Lake Michigan in Holland, and Lake Champlain in Burlington.

Back home now for a breather, I find myself considering my own town anew. It’s easy to see Washington as a town dedicated to media positioning, political backbiting, and social sparring. But there is another more human side to find if you look. Back to my neighborhood pool for that.

A morning shrine near my public pool. (Deborah Fallows)

There is a woman who spends almost every morning at a picnic table next to the pool, reading the paper or a book, with two corgi-looking dogs resting on the cool concrete beside her. She is there when I arrive and there when I leave. We say our hellos. (I was anticipating a British accent, but she actually spoke with a southern lilt.) One day I commented on the grapes she was eating, which she offered to me, and the small pile of tangerines she had set up, which reminded me of a Buddhist shrine.

Every day since, even if she has come and gone, she leaves a little something for passersby like me to enjoy—a design of orange peels, some fruit, and once, an amazing bird nest. I will miss her offerings once the summer has passed, the pool has closed, and she goes wherever she might go for the colder seasons.

But then I thought that just maybe she’ll be near our neighborhood’s public indoor pool.