Inland is a more important word than Southern at the start of that preceding passage. (People from California can skip this next paragraph, but it may be useful context for others.)

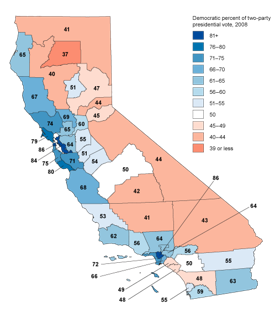

People outside the state typically imagine the dividing line in California as something like the old Mason-Dixon line, separating its territory north-versus-south. That is: the Bay Area vs. “the Southland,” the tech industry vs. “The Industry,” redwoods vs. palm trees, Stanford and UC Berkeley vs. USC and UCLA. In fact the really important line more or less parallels the Coast Range of mountains and divides the state west-versus-east, coast versus interior. On the western, coastal side are the biggest cities, the most famous companies and universities, the richest people, and most of the national mindshare of what “California” means. Plus the concentrations of Democratic voters, as shown by blue in the map at right. On California’s eastern, inland side are all of its deserts, most of its farmland, and a disproportionate share of its problems, from pollution to poverty to the worst consequences of the current disastrous drought. And most of its Republican districts. The importance of the coastal/inland dividing line also applies in Oregon and Washington, and—with an east/west switch—in China too.

(Welcome back, Californians!) The two cities I’ll be talking about in coming days are Riverside and San Bernardino, both of which are the county seats and principal cities in their respective counties, which also have their names.

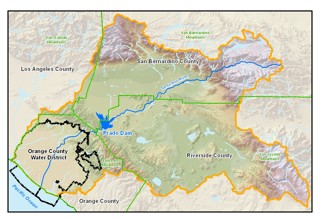

The two county-seat cities, San Bernardino and Riverside, have some rough similarities. They’re both medium-sized—200,000+ for San Bernardino, 300,000+ for Riverside—and are barely a dozen miles apart, both built on the usually dry bed of the Santa Ana “River” with scenic mountains all around. If you were visiting from Iceland or China, or for that matter from Pennsylvania, you might think of them as near twins. (A much smaller town between them, Redlands, is where I grew up.)

But the two cities’ histories are very different. San Bernardino is one of inland California’s older cities, first settled in the early 1800s, then becoming a major Mormon settlement in the 1850s (until Brigham Young called the group back to Utah before the Civil War), and through most of the 1900s developing as a big railroad and trucking center. Even when prospering—and in the mid-1960s it was prominent enough not simply to be mentioned in the song “Route 66” but also to have hosted the very first U.S. appearance by the Rolling Stones (which as a 14-year-old I saw)—it was a no-frills, no-nonsense, bungalows-with-small-yards blue-collar place.

Riverside’s modern development began much later, in the 1870s, as an orange-growing and inland-resort site, about which we’ll say more in later accounts. A major element in its current economic strength was the state’s decision during Pat Brown’s expansive late 1950s to convert what had been a Citrus Experiment Station into a full-fledged branch of the University of California system, UC Riverside. San Bernardino has a community college and a branch of the Cal State system but not a comparable research university.

We’ll get into more details of that later. For the moment, the point is that the past 30 years have overall been pretty good for Riverside, and overall extremely bad for its seeming twin of San Bernardino.

Through this time San Bernardino has lost, one after another, all the major sources of its blue-collar employment: a huge Air Force base, a railroad yard, a nearby major steel plant, much of its construction industry. A major Interstate freeway that had channeled traffic through town was moved 20 miles west. Although the city is now betting heavily on a warehouse-and-logistics complex as its future economic hope (as outlined here), the businesses that have returned have not come close to replacing the ones that left.

San Bernardino has a uniquely dysfunctional city-governance system, sort of a metropolitan parallel to the current zero-sum gridlock of national politics. Some cities we’ve seen run on the “strong mayor” principle; others, “strong city manager.” Because of San Bernardino’s unique and flawed charter, it has in theory a “strong mayor” but in reality a “strong nobody” system of government, and an electoral system so discouraging that that turnout rates are extremely low even by U.S. and California standards. Without getting into all of the details now, its exceptionally unworkable governing structure is much of the reason it’s one of the major still-bankrupt municipalities in the country and, as I mentioned in an earlier post, was recently ranked dead-last among American metro areas in job-creation possibilities. It’s the poorest city of comparable size in California. Its neighbor Riverside is about half Hispanic-origin in population; San Bernardino is about 60 percent Hispanic and about 15 percent black.

San Bernardino is a place that people with choices might rationally choose to get away from. Its prospects are as tough as those of any big city in America. That’s why my wife Deb and I have been so struck by people choosing to stay, and struggle, and work to improve the city. I will start with a group called Generation Now, and with two questions about their work. The first and more straightforward question is what they do. The second, harder, and more important one is why.

San Bernardino Generation Now, or SBGN, is not quite two years old. A group of young adults who are highly diverse, ethnically and by gender and education, decided to start working to supply one of the things their city most notably lacked: the kind of social capital and civic fiber that come from community organizations, public events, all the other activities that constitute “bowling together” rather than bowling alone.

The smaller, richer neighboring town of Redlands is practically spider-web-wrapped with civic organizations of all kinds: to support the library, the parks, the symphony, the schools, the churches, the university, the ailing, and many other causes. Riverside has fostered a civic identity as a “good place for families” town. San Bernardino has historically been short on comparable institutions, and the poorer and harder-pressed it has recently become, the more that fabric has frayed.

But starting in 2013, Generation Now began organizing local people at forums to discuss the city’s challenges, and to increase their turnout at the polls. You can read an early account of the group’s plan to “take back San Bernardino” from the San Bernardino Sun here. It ran candidate forums to discuss proposals for the city’s future, and put the results on YouTube.

Some of the founders were artists, and they organized a program of painting murals in battered-looking parts of town. SBGN members rehabilitated parks, planted gardens, picked up trash, organized community-wide picnics and music festivals, and generally kept moving. You can see an Instagram page about their activities here, plus see their main Facebook page here, or see the video below about some of their park-cleanup efforts. If you’re wondering about “civic fabric” in economically struggling, “majority-minority” communities, this is worth a look.

There’s a lot more I could say (and might still) on the what of Generation Now’s efforts. But for now let’s skip ahead to the why.

A few weeks ago Deb and I talked with a group of its members, those shown in the photo at the top, and asked a version of the question that’s been on our minds whenever we see people soldiering on in objectively very tough circumstances when it would be easier and more “rational” just to go somewhere else.

Stated this way, the question might seem needlessly crude. But so much of modern economic theory—like, just about all of it—so much of our politics, so much of our analysis of how young people make life trade-offs is based on narrowly utilitarian consideration of “what’s in it for me, now?” that the question at least needs to be asked.

I’m not going to resolve this question here. But let me mention three themes that came through in our talk with the SBGN crew.

• Anger. “I was pissed off,” Michael Segura, who is wearing the baseball cap in the photo at top, told us. “By the time I was old enough to vote, everything was in such terrible shape in San Bernardino.” His response, with his colleagues, was to try to mobilize the city’s disaffected young people and minorities to register, participate, vote, and otherwise shift the culture and policies of their town. The members of SBGN need no one to tell them about the ways the city’s business, educational, and political leaders had betrayed them. The surprising aspect is their decision to channel frustration and suspicion the way they have.

• Faith. Perhaps it should not be surprising that so many of the people working to change this troubled town said that religion was part of their motivation. For better and worse, faith has always been one of the great non-“rational,” motivators—along with family, nationalism, place-based loyalties, romantic love, etc. But religious organizations are clearly a big factor in the effort to improve San Bernardino. For instance, a group called ICUC, Inland Congregations United for Change, and its director Tom Dolan, have been inspirations for Generation Now. Among other lessons they conveyed was the non-obvious point that the group should not incorporate itself as a normal 501(c)(3) nonprofit group. As a normal nonprofit, it could not engage directly in local politics — and changing the political complexion of the city is an important part of their goal. ICUC is part of a larger national faith-based movement for community organization called PICO.

• Modeling the change you believe in. The group organizes park clean-ups and public painting projects partly because it wants to parks to be clean. But even more, we heard from Jennica Billins (third from left in the top photo), SBGN want to show others in the town what it looks like to pitch in for community betterment. “It even comes down to greetings your neighbors, big and little ways of modeling the behavior you would like to see,” Billins said.

“San Bernardino is absolutely coming up,” Jennica Billins said. “But I hope it doesn’t come up just in the usual way, with some other people moving in. We’d like to make it work with our own people.”

The inequalities and frustrations of today’s American life are as clearly evident in San Bernardino as anywhere else. This is an account of the way one group has chosen to respond.