All Ferris wheels — from the popular county fair rides to the famous 135-meter-tall London Eye — can trace their roots to Galesburg, Illinois. This is because George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr., named after the city’s founder, George Washington Gale, happened to be born in Galesburg in 1859.

Ferris would go on to create the popular amusement ride that still bears his name today for the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. This was in response to the Exposition directors’ call for an invention that would “out-Eiffel Eiffel,” after Gustave Eiffel unveiled the tower bearing his name in Paris during the International Exposition of 1889.

While many outside Galesburg might not know about the city’s connection to the Ferris wheel, the people of Galesburg want to change that. The recent embrace and championing of Galesburg’s Ferris wheel history is one of many efforts led by the community to shape a new identity after decades of transitioning away from being an industrial center.

Galesburg was founded in 1837 when George Gale chose the area as the home of a manual labor college, known today as Knox College. Galesburg’s identity as a manufacturing town seemed fixed from the start, until, well, it wasn’t.

Sitting on the western edge of the Rust Belt about 50 miles northwest of Peoria, Galesburg is home to 30,052 today. The population there peaked in 1960 at 37,243, and then began a steady decline ever since.

In 2004, the Maytag Corporation, once Galesburg’s largest employer, announced it would close its refrigerator factory. Maytag moved production to Reynosa, Mexico and exported 1,600 jobs from the community. Without the 52-year economic anchor there to shoulder a significant portion of the load, remaining residents were then saddled with higher property taxes.

The nation noticed. Then-candidate for the U.S. Senate from Illinois Barack Obama discussed Galesburg’s news in his national-debut speech at the Democratic National Convention that summer. Ten years later, national outlets were still wondering whether the “Appliance City” would make it.

In June 2019, Phoenix Investors purchased the 885,000 square-foot former Maytag facility. They began construction work on the site in July 2020. A month later, announcements came that Corteva Agriscience would lease 300,000 square feet of the repurposed building — continuing an emerging pattern in Galesburg of “adaptive reuse of many underutilized and vacant buildings,” Ken Springer, president of the Knox County Area Partnership for Economic Development, told The Register-Mail:

“These include the former Armory building, the former Walmart on Henderson Street, the former Outboard Marine Corp. industrial building on McClure St., the former Shopko building, the former JC Penney Building, the former K-Mart building, the former Aldi building on Main Street and now the former Maytag manufacturing facility.

Step by step, this community is revitalizing itself. We still have a ways to go, but there is no denying that significant progress has been made in just a few short years.”

About four years ago, according to Steve Gugliotta, the city of Galesburg’s planning manager, a national art supply company called Dick Blick moved into one of the two original buildings. It continues to operate there. The other original building still houses Corteva Agriculture. Now they are using the space as a regional distribution hub for agricultural-machinery products, including wind turbines. Phoenix Investors is finishing renovations on the south side of the building that Gugliotta says he hopes new tenants will occupy soon.

While manufacturing used to be the economic driver of Galesburg’s economy, today it ranks fourth overall, employing less than 10 percent of the workforce. Maytag wasn’t the first or last company to leave Galesburg. The Gates Corporation, Butler Manufacturing, and Outbound Marine Corp. are just a few that have downsized operations or shuttered doors. More people in Galesburg, as in much of the country, now work in health care and social assistance (just over 17 percent) and education and retail trade (each at 15 percent). Among today’s larger employers are the BNSF Railway, OSF Healthcare, and Knox College.

Companies leaving or moving production elsewhere one after another perpetuated a narrative in the town that if residents, too, were to seek better opportunities, they had to — like the companies — go elsewhere. The director of the Galesburg Airport, Harrel Timmons, started his own business, Galesburg Aviation, in Galesburg in 1969. While his doors remain open, he has seen many companies come and go in the 53 years he has lived there.

“Galesburg went through a period when things weren’t going so well, and everybody got down,” Timmons said. “A lot of people were saying, ‘the last person out of Galesburg, turn out the lights.’” According to a 2005 Chicago Tribune feature, a billboard in Galesburg even featured that message—which has become familiar in many towns as a shorthand for manufacturing decline. (The phrase appears to have originated in Seattle in the 1970s, because of downturns at Boeing and in the lumber industry. The main problem for Seattle’s economy these days is of course hyper-rapid growth. This is an indication of how profoundly a city’s or region’s economic narrative can change. As Deb and Jim Fallows recount in the Our Towns documentary, in the 1980s it was even a saying in Bend, Oregon—another of today’s shorthands for very rapid growth.)

Creating change — personally, institutionally, or otherwise — can be as difficult as stopping a train that is going full speed in one direction, then forcing it in the opposite direction. The cascading dominos of businesses shuttering in towns like Galesburg can feel like a rolling train impossible to slow down let alone reverse course.

But those who were committed to staying, like Tom Simkins who’s spent much of his life in Galesburg and the nearby town of Abingdon, wanted to try something, find some way to keep the lights on.

“Maybe revitalizing Galesburg isn’t about the jobs,” Simkins said. “Maybe it’s the look and feel of the community.”

Another way of putting it: “quality of life,” which is what Galesburg residents decided to do. The improvements that together amount to improved “quality of life” may not always be sufficient to reverse a town’s economic fortunes. But they appear to be necessary. According to a recent Brookings Institution report, it looks like a plan that can pay off both in the short- and long-term.

“After estimating quality of life (what makes a place attractive to households) and quality of business environment (what makes a place especially productive and attractive to businesses) in communities across the Midwest, we found quality of life matters more for population growth, employment growth, and lower poverty rates than quality of business environment.”

John Austin (who’s contributed to the Our Towns website), Amanda Weinstein, Michael Hicks, and Emily Wornell, “Improving quality of life—not just business—is the best path to Midwestern rejuvenation,” Brookings Institution, Jan. 26, 2022.

Sandra Gray, the Director of Advancement Services for Knox College, calls these factors – the conditions of the natural and built environments; access to recreational and leisure activities; education, social belonging, a feeling of being safe – the “soft” parts of community development. That is the contrast with “hard” parts, which could be thought of as traditional economic investments. According to Gray, investing in parks, history walking tours, decorations, little free libraries, and clean streets are “the things that are attractive to a family when they are looking for a place to live.”

Simkins is one of the many people at the forefront of these quality of life enhancing efforts in Galesburg. He recently retired from a career in Galesburg that included 35 years as a first responder in the fire force, part of that time spent as the fire chief, and in emergency management.

Simkins said the unique perspective he gained as a first-responder caused him to consider how he might be a member of the community in a deeper way. Reflecting on his time in the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program, he said, “one of the things that stuck with me was the notion that a fire chief should be more than just a fire chief. They’re a leader of the community, and they should branch out into other things. They shouldn’t just be worrying about fires. They should worry about the whole community.” And he has applied this philosophy in Galesburg, where he is working to repair Galesburg’s relationship to itself.

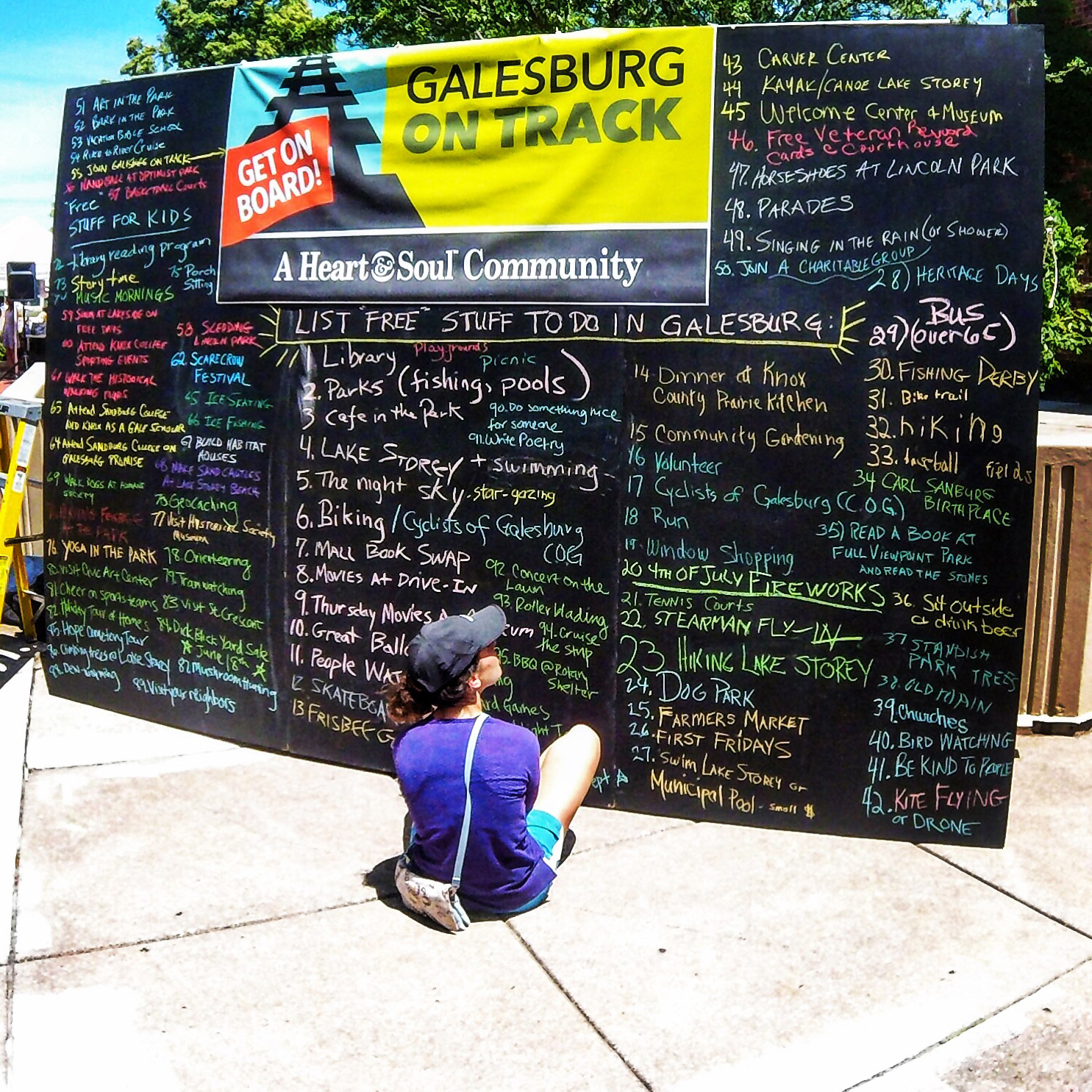

While Simkins has coordinated many revitalization efforts of his own, he’s also contributed to other efforts in Galesburg at the Rotary Club. Since 2015, he’s been a part of “Galesburg on Track,” the name of the town’s Community Heart & Soul (CH&S) project. CH&S is a citizen-led, long-term town development process. For the record, they are an Our Towns partner and supporter. The Galesburg Community Foundation spearheaded the effort to bring CH&S to Galesburg and, with financial support from the Galesburg city council, hired Deborah Moreno as the project coordinator.

Moreno grew up in Evanston, Illinois then moved to Galesburg to attend Knox College. She works in Galesburg now as a local journalist and creative writer. Moreno said she approached leading the CH&S process with the same philosophy she uses in telling stories for a living: “start with a listening ear.”

In the early phases of the Galesburg on Track project, residents came together for a Community Summit — in the city’s central fire station — to identify their collective values, and, based on them, create action plans that guide town planning. To Galesburg, these values included, among other things, taking pride in their history, cultural heritage, and town image.

Enter George Ferris’s Ferris wheel. Starting in 2018, Galesburg began incorporating Ferris Wheel motifs throughout the town. The city plans to have a fully operating Ferris Wheel Park by 2028 featuring, you guessed it, a Ferris wheel, to draw locals, visitors, and new business developments. The Galesburg on Track project also includes plans to honor the town’s part in the country’s anti-slavery movement – which can be traced all the way back to the city’s founding in 1837 by abolitionists from update New York, led by George Washington Gale.

Home to the first anti-slavery society in Illinois – and the site of the fifth Lincoln-Douglas debate in 1858 – Galesburg was a major stop along the Underground Railroad. Galesburg residents want to bring this history forward in their town’s identity and image, and the Galesburg on Track action plan states: “Galesburg continues to honor its history as a stop and the underground railroad through historical reenactments and participation in various historical projects.”

Simkins has also been at the forefront of beautification in the town that is promoting a more positive town image. The Community Blue Ribbon Award was reinstated in Galesburg recently to recognize improvements to the exteriors of residential properties. Simkins has been leading efforts to adorn Galesburg’s historic streetlamps that date back to the 1920s with red bows around the holidays. Retired firefighters recruited by Tom are volunteering to paint fire hydrants, place petunia displays at railroad crossings, and paint plywood to blend into the color of the buildings they are used to board up, so it is more aesthetically pleasing in the neighborhood.

It’s common to hear people say not to sweat the small stuff. Tom disagrees. The small stuff, he sees it, adds up.

“Here, you can really make a difference. If you are passionate and want to do something, you just need to start doing it,” Simkins said. “And it’s funny how that snowballs, and how it’ll attract more people when they see things.”

This report is part of an ongoing project in cooperation with Community Heart & Soul, which is a supporter of the Our Towns Civic Foundation.