Xizhou. Nearly six years ago I wrote an article in the magazine called “Village Dreamers.” It was about an American couple, with two young-teen children, who had spent many years in China and had decided to devote their time, their savings, and much of their future to the long-shot dream of rehabilitating a town in the remote, Himalayan-foothills reaches of China’s southwestern Yunnan province.

Their little town, Xizhou, had once been home to prosperous merchants and still possessed a large number of courtyard houses, temples, and other classic-style, once-beautiful buildings. Most had been spared destruction during the Cultural Revolution through the good fortune, as it appeared in retrospect, of having been commandeered as People’s Liberation Army barracks. Here is a sample of how one of them looks now, after its restoration as a conference center and retreat.

You can read more about this family, Brian and Jeanee Linden and their children, here, and see a video of them in their town back in 2009 here. When we were reporting on them, as the video suggests, everything about their plans was tentative. We were among the first-ever customers of what they hoped to make into a retreat so exceptional that people would make the very long trek from China’s own big cities, to say nothing of the rigors of a trip from overseas, to have a chance to see it.

As it happens, the Lindens’ big bet on Xizhou appears to have paid off. They’ve gone from strength to strength: winning awards as having the “best small hotel in China,” attracting Chinese and international conference groups, being written up in the NYT, and acquiring and rehabilitating additional structures. You can read all about it, and them, here.

Yellow Sheep River. Not every quixotic venture we have seen, and crossed our fingers for, has worked out so happily. Shortly before we visited the Lindens, we reported on a roughly parallel effort in a small village in China’s arid, remote, impoverished, but stunningly beautiful Gansu province.

This was the effort by a Taiwanese-American man named Kenny Lin to will into success a 5-star conference center and resort hotel in a little town called Yellow Sheep River, which was so far from anywhere that the last stage of the journey there is on horseback. (With lots of yaks looking on.) Kenny Lin undertook this as a labor of loyalty and love for a lifelong friend who had pioneered the project and then suddenly died before its fruition. That’s the story I told in the magazine here.

The forces of remoteness, the mysteries of the Chinese five-star resort business, plus unknown other factors gave this quest a sadder conclusion. A little more than a year ago I relayed the news that Kenny Lin and his foundation were offering free title to the Yellow Sheep River conference center to anyone willing to try to make a go of it. Dreams would be called something else if they always came true.

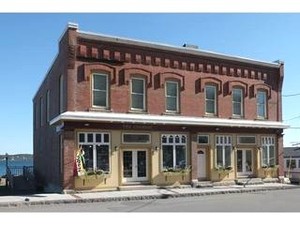

Eastport. A little more than a year ago we wrote in the magazine, and did web posts and a Marketplace broadcast, on the hardy group of citizens trying to revive the also-beautiful and also-remote city of Eastport, Maine.

The town has only 1,300 residents, but each of them seemed to have four or five jobs, divided between those that would keep their families going and those that would give the town new life and appeal. We wrote about a number of them—Captain Bob Peacock, Linda Godfrey and the other Women of the Commons, the brothers Hugh and Edward French and their families, Chris Gardner, and on through the other 1,290 or so—and were impressed by the ingenuity and effort by which they were determined to use natural beauty, and community commitment, to overcome distance and establish their community as a place people would—and should—make the effort to go and see.

Now we come to Ajo.

In two posts this past week, my wife Deb has set up Ajo’s challenge, and its hoped-for response. The challenge is actually very similar to those faced by both Xizhou and Eastport. Xizhou had once been part of an important trade route for tea, horses, and salt. Those days are gone. Eastport was once one of the centers of the Atlantic sardine-canning industry. Those fish are mainly gone, as are the canneries and the jobs. (The city does have an annual Sardine Drop festival to welcome in the new year.) I’m leaving Yellow Sheep River off this list, because it never had a big economic base that suddenly went away.

In Ajo’s case, the source of lost wealth is its adjoining, vast, open-pit copper mine. For a century before 1985, the mine employed most people in town. Since then, it has employed almost no one.

For a while the city limped along as a destination for what for the editor of the Ajo Copper News, Gabrielle David, described to us as “blue collar retirees,” who may have come in RVs or with tents to stretch a pension as far as it could go. Now it too—like Xizhou, like Easport—is trying to make beauty and a specialness of place overcome the obstacles of remoteness.

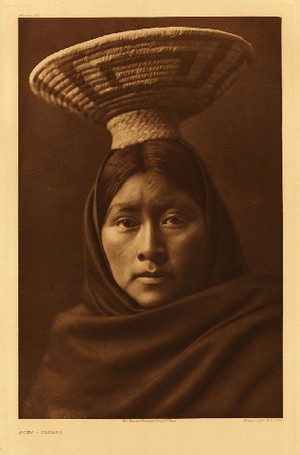

In comparison with these other towns—Eastport four-plus hours by car from Portland, Xizhou closer to Burma than to any sizable city in China —Ajo is barely “remote” at all. It’s a two-plus hour drive south from Phoenix, or 45 minutes south from the also-small Gila Bend. (Which was the way we came, as explained here.) The beauty-of-remoteness it has to offer is mostly natural, as the closest settlement to the under-appreciated and breathtaking Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, about which we’ll say more in later installments; as a waypoint toward the also breathtaking expanses of the Tohono O’odham Nation. (For reference, until a formal name change in the 1980s the tribe had been known in English as the Papago.)

I don’t dare offer any photos of the landscape, because they’d just look like amateur versions of what you’d see in Arizona Highways. Instead I’ll use this classic century-old Edward Curtis portrait of a Tohono O’odham woman, at right.

The other beauty, surprisingly, is architectural and civic. Some mining towns or commodity centers are big rough-and-ready messes. Others are somehow infused with touches of culture—think of the opera house in Manaus, as told by Fitzcarraldo.

In an upcoming post Deb will explain exactly why (with unexpected connections to Eastport) Ajo ended up being one of the mining towns whose bosses had City Beautiful aspirations. For the moment the point is that they did—and the “good bones” remnants of those early ambitions, in the form of its grand central plaza, and the historic Curley School, were fortunately never bulldozed and now give it material to work with (as Deb explained here).

Here is why I’m writing about Ajo—and Xizhou, and Eastport, and even Yellow Sheep River—late at night, when we have more installments in their saga to come. It is to emphasize the emotional power of seeing social capital being created, as we now realize we have done in all these different-but-similar places.

Everyone knows about financial capital-creation, and we assume it is carried out on Wall Street or Sand Hill Road or by gnomes in Zurich. Social capital is as precious and necessary as financial capital, we’ve come to believe. (In China it’s scarcer and more important than in America, but that’s for another time.) And it has been surprisingly moving to get to know people who are investing themselves in the lives of their communities, even if conventional economic or career-strategy analysis might suggest that this is a waste of time.

Here are two closing illustrations from Ajo. One involves the wonderful young people of the National Civilian Community Corps, or NCCC. As Deb and I have traveled, now, in every corner of the country, we’ve been sobered by reminders of how much the New Deal-era WPA changed the face of the country, and how fast it did so. What would it be like to have such projects underway today?

The NCCC, a branch of Americorps, is one modest answer to that question. On our visits to Ajo we saw the members of this NCCC team, themselves from every corner of the country, working all day long to build a new civic facility. These were great young people, and you’d feel better if you had met them, as we do. For the record, those in the picture are (not in order): Shamare Allen, of Long Island, New York; Reana Thomas, of Dublin, Ohio; Tanner Lee, of Burlington, Connecticut; Ryan Verstraete, of Eaton Rapids, Michigan; Tiffany Farrar, of Bethlehem & Bronx, New York; Elizabeth (Biz) Austin, of Springfield, Vermont; Sahira Hurley, of Augusta, Georgia (in the green shirt, the team leader); Leahray (Lulu) Gallo, of Pollick Pines, California; and Brendan Faris, of Berlin, New Jersey.

Twenty years ago my friend Steven Waldman wrote a great book called The Billabout the legislation that established Americorps. Another time I’ll tell some of the stories of Americorps members we have seen and how the period of service has changed them. (And how meeting them has changed us.)

We’ve also been impressed by the ability of the people trying to recreate Ajo, including Tracy Taft and her colleagues at the International Sonoran Desert Alliance, to enlist others to share their belief in the importance and possibility of creating something special in a remote locale. On our first visit to Ajo, we met a young couple from the Boston area, Emily Raine and Stuart Siegel, who had come through town more or less by accident, as part of a planned year-long see-America-by-car-with-dog tour they called their “Big-Ass American Adventure.”

When we came back a month later, they’d signed on to run the brand-new Sonoran Desert Conference Center (with embryonic web site here), and they were busy at work preparing for its opening session on the grounds of Ajo’s historic Curley School. Stuart Siegel’s Tumblr chronicle of their travels was focusing on the evolving look of Ajo (including a shot of their taking us to the airport in Gila Bend), and on her blog Emily Raine had produced an essay on 10 Things to Love About Ajo, a place in which I am confident neither of them had previously imagined spending more than one day.

What’s the theme, and the moral? It is more encouraging and emotionally powerful than you might think to encounter people who are giving their all to pull off a long-shot project, and for rewards that would never be captured in an IPO. As to why they do it, we’ll be reflecting on that. Perhaps as a start we’ll hope at some point to see a conference circuit linking the dreamers of Xizhou, Eastport, and Ajo. Kenny Lin and his wife Rebecca should be invited too.