So, we decided to base ourselves this winter in southern California, and to explore the West, the Southwest, and even the Northwest from there, as weather permits.

For a few weeks, we went through the familiar drills of tying up all the loose ends at home: wrapping up work projects, canceling the papers, holding the mail, and leaning on the dearest of friends to keep an eye on our house.

How had Steinbeck prepared, I wondered? What did he pack into Rocinante, his customized truck, which he gamely named after Don Quixote’s horse, for his 3-month journey? Could I find some tips?

Well, for starters, this was a sturdy pickup truck, not a composite-construction weight-sensitive four-seater propeller plane. The truck, he wrote, was:

[A] camper top including a double bed, a four-burner stove, a heater, refrigerator, and lights operating on butane, a chemical toilet, closet space, storage space, windows screened again insects..

He seemed to throw in everything but the kitchen sink:

I took far too many things, but I didn’t know what I would find. Tools for emergency, tow lines, a small block and tackle, a trenching tool and crowbar, tools for making and fixing and improvising. Then there were emergency foods…

I thought I might do some writing along the way, perhaps essays, surely notes, certainly letters. I took paper, carbon, typewriter, pencils, notebooks, and not only those but dictionaries, a compact encyclopedia, and a dozen other reference books, heavy ones … I also laid in about 150 pounds of those books one hasn’t got around to reading…

Canned goods, shotgun shells, rifle cartridges, tool boxes, and far too many clothes, blankets and pillows, and many too many shoes and boots, padded nylon sub-zero underwear, plastic dishes and cups and a plastic dishpan, a spare tank of bottled gas…

OK, Steinbeck did not set a promising example. Everything about small-plane flight means being aware of “weight and balance” issues. (When we are taking friends for rides, we must indelicately ask, or guess, how much they weigh.) The maximum gross take-off weight of our plane is 3,400 pounds. The “basic empty weight” of the plane is just under 2,400 pounds.

This leaves us 1,000 pounds to work with: For fuel (gasoline at six pounds per gallon, full tanks on both sides means 80 gallons or 480 pounds); people (300 pounds for the two of us); and the remainder for everything else. That everything includes: necessary plane gear, including emergency equipment and tools, tie-down chocks and rope, first aid. About 60 lbs. of clothes, a hefty few bags of electronics (three iPads, three laptops, GPS backup, cell phones, cameras, wires, plugs, hardware of all sorts), a bag of assorted Christmas presents, Jim’s flight bag of gear and backup systems, a small coolbag of food and water, since you never know what you’ll find upon landing. My tried and true grocery list includes: beef jerky, cheese sticks, granola bars and some water.

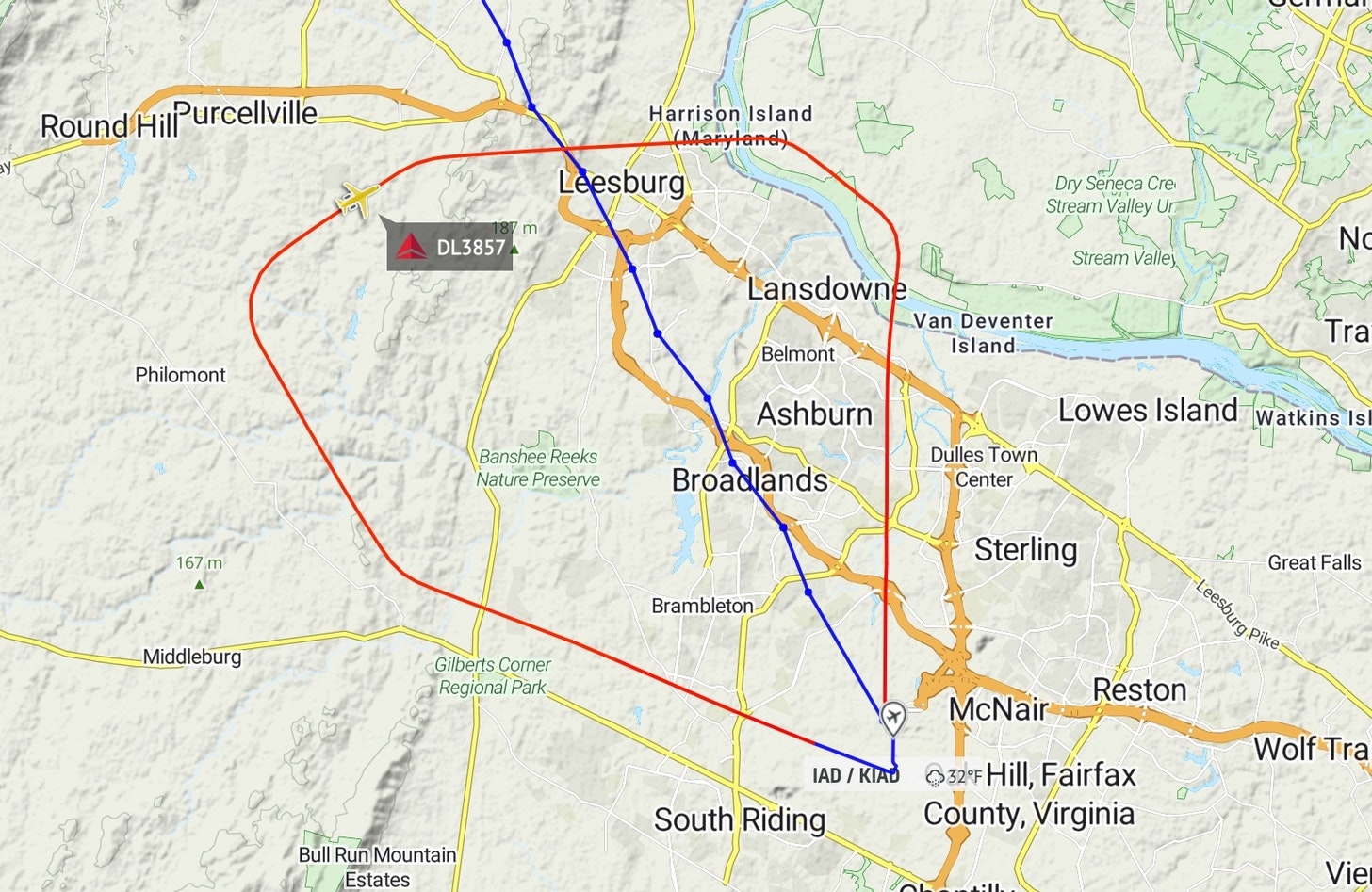

Our departure was, in the end, a hurry-up affair. We had an afternoon window of about two hours after the lift of morning fog and before an early winter storm would roar up from the south to DC. We knew we wanted to get ourselves over the Appalachians and beyond the western edge of the storm.

To stay within the “center of gravity envelope”, we packed about 120 pounds in the rear cargo hold, saving the rest for the back seat, and of course us in the front seats; any more weight in the back could drag the tail down, not a good thing. At the last minute, we jettisoned a 35-pound duffle bag and stopped fueling the plane 15 gallons short of “topping it off,” which gave us 90 pounds of weight to work with. I’m not quite sure what we left behind!

With a few hours before sundown, we took off for Huntington, West Virginia, our best guess for a big enough town with a long enough runway, a late-opening general aviation terminal (FBO, for fixed base operator) to help us find a last-minute hotel and transport to get there.

The air was crystal clear; the headwinds were strong, about 35 knots straight at us at times. We had returned more or less the same route from Charleston, West Virginia a few weeks earlier, and enjoyed even stronger tailwinds, clocking us in at a record 217 knots of ground speed for a time. But heading west, we were paying, hitting an over-the-ground speed of a measly 130 knots. (When run in gas-saving mode the plane cruises at an airspeed of just under 170 knots, or about 195 miles per hour.)

I had hoped to fly a little farther south, over terrain we had been before toward Asheville, North Carolina and Knoxville, Tennessee. I wanted to fly over the Great Smoky Mountain National Park. More than 50 years ago, a writer named Paul Brooks, who was also later the editor of Houghton Mifflin publishers, had written a series for The Atlantic that included his hikes through the Great Smokies. In the intro to his May 1959 piece, called “The Great Smokies,” the editors wrote:

He and his wife have camped, paddled, walked, fished birded, and chased butterflies from Thoreau’s Concord River at their doorstep to the Olympic Peninsula and the Oxford Canal..

He wrote:

From the air, you see a sinuous green-clad ridge, with smaller ridges going off in every direction, separated by deep valleys and tortuous streams..

In a day’s climb, one can travel through successive biological zones, equivalent from a journey from Southern Tennessee to the Canadian border, from the great tulip trees in the valleys to the virgin spruce-fir forests of the summits, where the climate is equivalent to that of the coast of Maine.

I remembered this sight from nearly a year earlier. We might fly it again one day, but it would not be that day.

* Thanks for help digging through The Atlantic archives to Jennifer Barnett, Nora Biette-Timmons, Andrew Giambrone, Serena Elavia, and Audrey Wilson.