Montgomery County traffic, Cirrus Four-Three-Five Sierra Romeo taking Runway One-Four, VFR (visual flight rules) departure to the west, Montgomery.

And with that, we were off in our small Cirrus airplane for the last official journey of our American Futures series for The Atlantic, flying away from frigid Washington D.C. and its political turmoil, on a southerly route to California.

We have flown over 60,000 miles during the past three-and-a-half years, from the upper Midwest to Maine, south through New England and the Mid Atlantic states to Georgia and Florida, sweeping through the deep south, to Texas and the southwest, up the central valley of California to Oregon and Washington, and closing the loop to Montana, all the while snaking in and out of the so-called flyover country, the middle of everywhere through Wyoming, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, West Virginia, and much of the rest.

“Flyover” to us has meant landing in dozens of towns for jam-packed visits of a week or two, often returning for unfinished business, reporting, or nostalgia. The purpose of this last journey is a little different. Our destination is sunny, warm, mind-clearing and political soul-cleansing inland southern California, to Jim’s hometown of Redlands. We plan to ponder all we’ve seen and try to make some sense of it on a more composed canvas than the pointillist collection of hundreds of blog posts that we have written along the way.

***

From experience, we anticipated that the journey would be unpredictable and exciting. Flight in a small plane is always that way: you don’t know which surprising event will occur, but you can always be sure that one or more will—sometimes good, sometimes bad. We are never disappointed, and always surprised anew by the dramas airborne, by the perspectives on the unfolding country below, and by the snapshots of life on the ground in places we land, many of which we’d never been to or even sometime heard of before being steered there for one reason or another.

Our leave-taking was not auspicious. Our planned departure for Sunday, and then for Monday came and went: the weather was too bad. We were heeding our only cardinal rule, which is that weather comes first, and there is no place we really have to be, ever. Cold, wind, snow, and icy conditions gave us a few more days to organize at home and winnow the next 6 months’ belongings—clothes, flight gear, portable technology, emergency supplies—into the 140 pounds the plane could carry, besides us and a reasonable amount of gas.

Finally, Tuesday looked like the day. It was still a blustery 29 degrees in Washington D.C., up from the teens two days before. But the clouds were high, so we could fly below them without having to file an “instrument rules” flight plan or worry about icing on the wings. (If you’re in the clouds in wintertime, you’re probably going to be in icing conditions, which are dangerous and have to be avoided.) We bundled into clothing layers so thick that I had to loosen my seat belt, a complex system of straps not unlike in toddlers’ carseats. I stretched my headset to fit over a heavy knit cap. Jim unplugged the plane’s engine from its overnight warming station. After all that, the sound of the motor turning over quickly, and I would add proudly, was our signal.

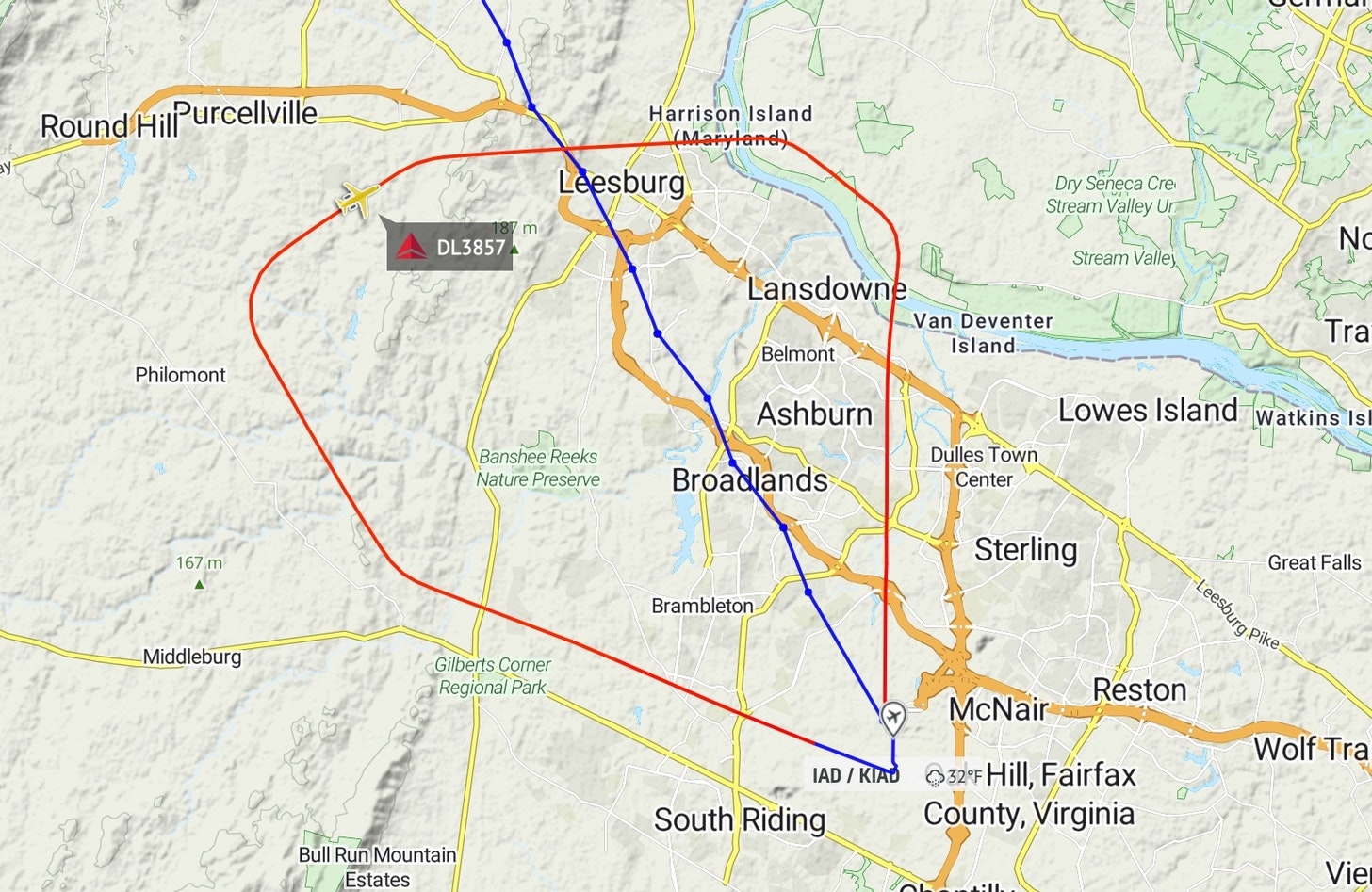

The air traffic controllers, (ATC), my heroes of the sky, guided us through the busy Dulles airspace, on a shortcut south. We expected headwinds, but not the strong 40 to 50 knots direct headwind blasts that slowed our ground speed from our accustomed 170 knots (about 200 mph) down to measly 109 at times. I was grateful for my natural sea legs, dating back to a childhood of pounding over waves in small sailboats, which translated well to the bumps and blips from gusty winds aloft. This part of the journey wasn’t for the faint of heart or stomach.

Inching over Virginia, we began to wean ourselves off the frenetic breathlessness of political news that saturated our hometown by listening to the slow-paced Senate committee hearings for some administration nominees on our Sirius XM radio.

We stopped for cheap gas in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Just beyond that, the snow had melted and given way to long stretches of brown earth. We tried out a few different altitudes before settling as low as we could, around 2500 feet, where headwinds were a bit lighter. (Usually the lower the altitude, the weaker the wind.) Outside, the temperatures began rising. We flew over the catfish farms and the erratic geometry of forest-clearing.

We were chasing the 5:06 PM sunset in Demopolis, Alabama, our hoped-for destination, to get in before dark and before the 5:00 PM scheduled closing time for the small airport office, called the FBO, or Fixed Base Operator in general aviation terms. We chose Demopolis for nostalgia this time, as Jim had spent a good part of the summer of 1968 around Selma, Montgomery, and Demopolis, as a teenaged very cub-reporter for a civil rights newspaper called the Southern Courier, writing about voter registration and other civil rights efforts. We wanted to give the town a look nearly 50 years later.

About ten minutes out, at just before 5 o’clock, Jim made radio contact with the FBO. Jason, the manager there, told us no rush to beat the 5:00 PM deadline, that he would stick around. That was welcome news to me; as part of my self-designated ground support, I usually arranged a motel and transportation before we arrived, a lesson learned over the years after some unhappy after-hours arrivals at rural airports, with no way into town and no place to stay. This time, our plans had been too unsure to make any bookings.

But we were lucky. At the end of a long departure and a very long day, it all worked out. With generosity exceeding even Southern hospitality, Jason lent us his own car for the night, saying his wife could come collect him later. We got the last room at the Best Western, which was booked with a team of workers who had come into town to service the planned outage of the cement factory. We were well on our way.