I arrived at Dodge City High School and headed straight for the lake. That would be Demon Lake, the acre-size pond at the side of the school grounds, where students practice their catch-and-release of bluegill, catfish, and bass.

Fishing in landlocked Dodge City, Kansas, you ask? No problem. They made a lake with reclaimed wastewater and stocked it. Dave Foster, the physical-education teacher and head football coach, was the visionary behind the pond project, and he will even teach lessons on how to fish. I had never heard of high-school fishing before—not even at my hometown high school in a fishing town on the south shore of Lake Erie. You can see a Facebook video of fish going into the lake in a video called “Channel Catfish Stocking at Demon Lake.”

Jacque Feist, the DCHS principal, and Mike Martinez, the associate principal, met me on a hot late-June morning, just after the Dodge City Fire Department had left the grounds. A false alarm, of course, but it was enough to empty the building for a while. Summer school was already in full swing, and the clusters of kids in various summer programs as well as a large number of students from a special-needs program spilled outside.

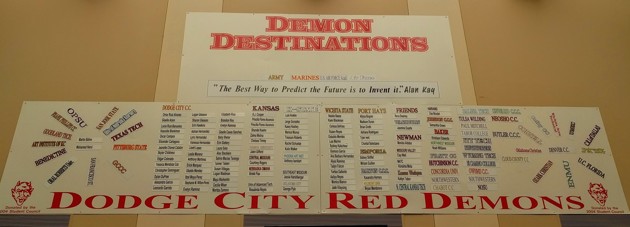

Feist and Martinez described the operating principle of their school: first kids, then teachers, then administration. They listen and build the culture in that order: start with the kids, not the other way around. Martinez said he wants this to be a place “where the kids can be themselves,” adding: “If five or six kids are interested in snakes, we’ll start a herpetology club, and they’ll be crawling in caves.” The school website lists more than 30 activity groups, from animation to a student-run business to the Outdoor Club, which includes not only fishing but clay-target shooting and archery. Beyond those activities, the school curriculum, with 16 career clusters, whets kids’ appetites in everything from welding to foreign service to communications.

The point of all this, Feist and Martinez explained to me, is to give every kid a place at the school and a sense that their interests—whether snakes or fish or art—matter and belong at the school. Just as they do. The result: “Demon Pride.”

Much of the reason that this inclusion is working, according to Feist and Martinez, is the shared ethic of the faculty and administrators and their solid backgrounds with Dodge City and its schools. Most of the adults at the high school have been around for a long time and have invested their lives and careers in the school and community. Feist, who exudes energy, has been at Dodge City schools for 29 years. Martinez, who looks impossibly young to claim it, has been there for 19 years. Martinez often refers fondly to his students as “kiddos.” (To my Midwest ears, the use of “kiddo” is a natural and friendly term. It may not ring that way to everyone; to my husband, Jim, a Californian, it sounded unfamiliar.) The superintendent of schools for USD443, as the Dodge City system is called, Alan Cunningham, is retiring this year after 43 years of service.

There is also little turnover among teachers. Many of them are homegrown or from other parts of the region. Only one of 12 new teachers hired this year was from out of state.

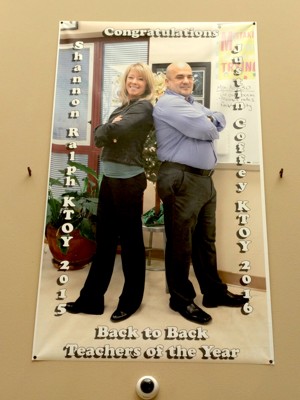

But reports of spirit and dedication aren’t just insider cheerleading. Those traits are recognized beyond the school doors as well. DCHS made history this year by claiming the Kansas Teacher of the Year honor for the second year in a row—math teacher Justin Coffey in 2016 and biology teacher Shannon Ralph in 2015. The larger-than-life poster of the pair, standing—of course—back to back, is the first thing you see upon entering the school. Even 12-year veteran school-bus driver Eduardo Escobedo won the “top transit-class school-bus driver” at the Kansas School Bus Rodeo Safety Competition.

There is little chance for complacency to settle into Dodge City, whether inside the schools or out. Responding to change is a way of life, as the demographics of the town, and even more so in the school population, rapidly expand. The USD443 enrollment, currently around 7,100 students, has grown by roughly 100 students a year since about 1992 and is predicted to continue at that rate.

Since the late 1980s, the Hispanic population in grades K–12 rose from 20 percent to 79 percent. Currently, the high school is 68 percent Hispanic, with another 7 percent designated as “other,” which includes African and Asian immigrant populations; the rest are Anglo. In the high school, 36 percent of students are English-language learners, and 76 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.

Keeping a school coherent throughout such dynamic changes is challenging. Each August, some 20 or 30 new immigrant students are likely to show up. The latest wave came from Guatemala. Many of the arriving Guatemalan kids, even at high-school age, entered a classroom for the first time and are illiterate. At home, conditions are often poor, and many families arrive with a rough history. Not to mention, assimilating into a new culture in America’s heartland is demanding.

Creating a safe and positive place for these students is important to the school system and to the city overall. That’s because Dodge City is no longer a stop on the road for most migrant families. The work opportunities, primarily at the meatpacking plants, are year-round and pay a wage that most workers consider solid. That means families are here to stay. “We need each other,” was the phrase Jim and I heard most often during our weeks in Dodge City: Immigrant labor keeps the packing plants operating, which keeps the town’s economy thriving. “We are a beef town,” many people told us.

Many of the children of Dodge City immigrants—unlike their parents— only know this way of life. The school administrators told me that their students “don’t see color,” which speaks to the Hispanic and Anglo communities’ mature integration within Dodge City. One sign of this particularly struck me: While kids often tend to hang out with their own ethnicity or race, the norm in Dodge City is to see the groups all jumbled up. In the school halls, at the public library, and at the public swimming pool, I saw kids blending together. However they were sorting themselves out, it didn’t look to be on the basis of ethnicity or race.

I dutifully asked Feist about the usual problems in American schools: drugs, alcohol, bullying, etc. “We have them all,” said Feist. Any other answer would have been suspect, of course. Looking at the school’s website or browsing through its newsletters confirms those typical problems do exist—but only because there are very accessible and visible social-services offered: counseling for students who are pregnant, who are already moms, who have incarcerated parents. There are also resources for everything from suicide prevention to cutting to alcohol.

In the September issue of the school newsletter, The Dodger, there was a reminder that drug-sniffing dogs would occasionally be present. In the April issue, there was an announcement about free dental checks. The March issueannounced the end of a program for reduced-rate physicals for athletics participation.

And how far does this spirit of goodwill extend? Beyond the school grounds and into the community. In a very Republican town in a very Republican state, which has chronically underfunded education and is in the middle of a nationally publicized round of cutbacks under Governor Sam Brownback, comes a surprise: Dodge City passed an $85 million school bond in June 2015 with 58 percent approval. For the high school, this means a new academic wing and expansions to some career technical centers, performing-arts space, and physical education. The residents of Dodge City are expressing their love for their schools with their pocketbooks.