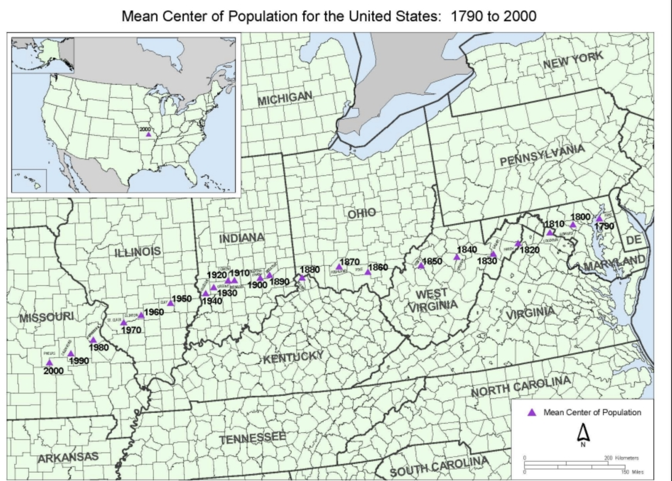

Americans have frequently moved: Consider how the geographic center of the population has shifted over the centuries, from east of Baltimore, when the Constitution was written, to west of the Mississippi now.

Tales of location and dislocation, voluntary or forced, are at the heart of American history and literature. They range from Lewis and Clark and The Oregon Trail, to O Pioneers! and The Grapes of Wrath—from The Warmth of Other Suns to On the Road, from Easy Rider to Thelma and Louise and Ladybird, and a thousand other illustrations before and after.

But of course Americans, like people of any culture, have at the same time craved connection, place, family, roots—the sense of being at home. This is part of our literature and life as well: The Education of Henry Adams in the Boston Brahmin way, and Where We Come From, by Oscar Cásares, as a very different recent illustration, with its account of life along the Rio Grande in Brownsville, Texas.

My goal is obviously not to sum up this unending tension in the national life. It is instead to tee up one practical aspect, as a prelude to this evening’s debate among 10 Democratic candidates.

Through America’s history, there has been a long dying off of the very smallest hamlets and settlements. In the 1870s, a small rural town might support several farming families, a general store and a school teacher and perhaps a newspaper publisher and an undertaker. Now if that village or settlement exists at all, it might just be a retired farm family, or someone working as an employee for a corporate owner, or someone who drives 50 miles to work in an Amazon or Walmart warehouse. Our literary reference here is Larry McMurtry’s The Last Picture Show, about the withering of his North Texas hometown of Archer City, Texas.

As we described in Our Towns and related articles, you can see the evidence of this smallest-town attrition perhaps most easily from above:

Even in South Dakota’s fertile East River, you can easily trace from low altitude what the railroads ushered in 150 years ago, and how their impact has ebbed. As we flew along one of the east-west lines that brought settlers into these territories and carried crops out to markets, we would see little settlements every few minutes. In the 1800s they were set up at roughly 10-mile intervals, an efficient distance when farmers were delivering their harvests by wagon. Now it seems that four out of five of those towns are withering, as farms are run with giant combines and crops are hauled by truck.

So, there will continue to be some communities—of a few hundred people, or a very few thousand—that are just too small to survive.

But what about those settlements that are large enough that they are not going away? Charleston, West Virginia, has lost more than a third its population, compared to its peak before the decline of the coal and chemical industries. Countless mid-sized cities in Pennsylvania and Ohio have fewer people than they did 30 years ago. The same is true in many Plains states.

And yet many of these cities, while smaller than they used to be, are still sizable in population terms and richly endowed with the physical legacy of their long decades of boom and growth. Big churches and synagogues; once-grand civic buildings and banks; department stores and concert halls—the many other reminders of the architectural ambitions and grandeur of an earlier American age. In some places across the country, the tattered parts of this heritage are being renewed. (For instance, like this, from Danville, Virginia.) In others, the decay goes on—fewer restored downtown apartments, more tattoo parlors and for-pay blood banks. But even the most struggling of these cities, unlike the Dust Bowl settlement where Caroline Henderson lived, is not simply going to disappear. Many of their people are not just going away.

Jason Segedy, of the planning department of the city of Akron, Ohio, wrote recently on his Tumblr—called “Notes from the Underground“—about what he called “the U-Haul school of urban policy.” That is the idea that if you can make people more geographically mobile—moving them out of a place where opportunities are dwindling, and into a place where new possibilities are opening up—you will have done much of the work that matters, toward making the U.S. economy fairer, more open, more inclusive, more dynamic, and so on.

People still are going to move, Segedy and others emphasize. But that’s become harder in various ways than it might have been a generation ago (for reasons Segedy goes into), and it doesn’t address the prospect of those who want to, or have to, stay.

Segedy’s whole post is worth reading—as is this complementary 2018 reported essay by Alec MacGillis in ProPublica, and Chris Arnade’s powerful and much-discussed book, Dignity. For the moment, I’d like to emphasize this part of Segedy’s argument, as part of his list of the modern limits of the “U-Haul solution” for America:

4) The Enduring Importance of Place: …When people left behind small communities in Appalachia or the rural South, in order to improve their individual economic prospects, it was undoubtedly a hardship for the people who were left behind in those places, but the number of people who were impacted was relatively small ….

That obscure, old, abandoned silver mining town in the Colorado mountains that you can’t name might have been a one-industry town, just like Youngstown was, but the similarity ends there.

Whether we’re talking about a smaller city like Flint or Youngstown, or a larger one like Cleveland or Detroit, we’re looking at established places with tens or hundreds of thousands of residents, surrounded by hundreds of thousands or millions more. The critical mass of people, and economic activity, even in a massively shrinking city like Youngstown, is staggering.

The notion that large numbers of people can just walk away from larger urban regions in the Rust Belt, without disastrous social (and, increasingly, political) implications is naive in the extreme. Encouraging everyone to abandon their friends, family, and community, and head for greener pastures might be a solid course of action for an individual person or household, but it is suicidal as a regional economic development strategy.

Nearly everything that matters in life is contradictory. Through our years of living in China, Deb Fallows and I were continually re-amazed about the opposites that were simultaneously true in that country: Rich and poor. Modern and backward. Tender and cruel. Controlled and chaotic—all true, all at the same time.

The American version of that outlook that I’ve come to believe, through our travels, involves opportunity and inclusion. America should make it easier for people to move—toward new places and possibilities, toward better versions of themselves. And America should make it better for people who stay. Again, as Jason Segedy put it:

In case I haven’t said it enough:

I’m not arguing that people should never move away from where they live.

But, I am arguing that we need a better answer than “You need U-Haul” for the economically struggling people in the cities of the vast post-industrial heartland of this troubled nation.

Formally these two approaches are known as “mobility-based” and “place-based” strategies. As Segedy, MacGillis, Arnade, and many others point out, “mobility” policies have usually seemed more high-brow and respectable than place-based approaches. Helping a talented young person go from a hick town to a research lab is a commencement speech-worthy illustration of the American Dream. Helping that hick town improve itself can seem like more pork barrel. But America’s version of China’s endless contradictions is that both of these opposites matter: Helping people, and helping places. A fairer chance for people who go, and a fairer chance for people who stay.

Where this is leading, in today’s installment, is my ever-increasing interest in groups, thinkers, organizations, and others who are trying to systematize “place-based” policies. To give just three illustrations, from many possibilities:

- The Orton Family Foundation, based in Vermont, has its “Community Heart and Soul Model,” aimed mainly at smaller and rural communities;

- Vibrant Community Partners draws on the work of Quint Studer, who has led a revitalization of Pensacola;

- Accelerator for America, which was founded two years ago by Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and his longtime aide Rick Jacobs, aims to be “a do tank, not a think tank” for place-based strategies. (I went to one of its sessions, in Dayton, early this month.)

The latest addition to this list is the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, based in Kansas City, whose focus over the years has been America’s entrepreneurial economy. Recently it released “America’s New Business Plan,” described in detail at this site, with a detailed set of recommendations for how cities and regions can foster the new businesses that, collectively, account for nearly all of the net job growth in the economy. “A lot of policy makers have a misguided emphasis on attracting big, established businesses,” Victor Hwang, Kauffman’s vice president for entrepreneurship, told me about this study. “Think of the big fight over cities trying to get [Amazon’s] HQ2. When you think about what could have been done with a fraction of that money, to foster new businesses, it’s very significant.”

What, in specific, could have been done? The Kauffman report, available online here and as a 25-page PDF here is designed especially to redress a funding-and-opportunity gap that has penalized women, people in rural area, and non-whites across the country. “Women, black, and Latinx entrepreneurs disproportionately struggle to raise the funds their businesses need,” the report says. “While 45% of men say that getting the money to start a new business is difficult, 63% of women report the same. On average, black entrepreneurs start with much less capital, have less family wealth to rely on, and are much less likely to get bank loans or other forms of investment than equivalent applicants who are white or of other racial identities.”

What makes this report valuable, from my point of view, is that it is chock full of specifics. They come in four main categories: 1) improving financing for new businesses; 2) sharing practical know-how in business operations; 3) streamlining regulations that burden small businesses in particular (as opposed to a general anti-regulation crusade; and 4) buffering some of the external risks that may deter people from taking a plunge-into-the-unknown by starting a business.

What’s an example of category four? Health-insurance costs and student-loan burdens. The Kauffman report goes into detail about proposals that could (in theory!) get bipartisan support, and that could create “a safety net that supports entrepreneurial risk-taking.” There is a lot more in the report.

Why mention this today? Because one more Democratic debate is about to begin. Lord knows there is a lot of other breaking news right now that is likely to dominate the questioning. But sooner or later, attention will turn again to the economic problems—both person-based and place-based—doing such damage in the country. Whoever emerges from the Democratic field will need ideas and plans for dealing with them. Fortunately the supply of such ideas is starting to grow.