This is a follow-on to the post earlier today, in an ongoing series about the most important infrastructure project in America today, the attempt under Governor Jerry Brown to build a north-south High-Speed Rail (HSR) system for California. This project is the subject of mounting controversy in California but has received much less national attention than it should. For the record, the installments so far are No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, with this as No. 4.

Since today’s two posts are quite long, I’ll let them sit for digestion before resuming the discussion in a few days. But since these two posts are related in outlook and source, it seemed worth getting them out during the same reading cycle.

Last week, a California writer named Chris Reed took me to task for naiveté when it came to HSR. (“7 Ways James Fallows is Wrong About the CA Bullet Train“) His real object of criticism was of course not me but the plan itself, of which he is a long-time opponent. What follows in this post is the gist of his seven-point critique, with responses from the same man I quoted earlier today: Dan Richard, head of the High-Speed Rail Authority.

I’m presenting them with the goal of letting a worthy exponent of each side lay out his case. And I’m presenting them in full-length version on the assumption that anyone who doesn’t care can skip right over, while anyone who does may want to know the detailed back-and-forth. Each of Reed’s critiques is in itals, followed by Richard’s responses. In the exchanges, Dan Richard directly criticizes Chris Reed’s logic and evidence. But what he says is milder than judgments Reed offered about the plan’s creators, or about me, so I figure it’s fair to leave those remarks in.

[Reed starts his list of seven complaints]1. All the wonderful things the train allegedly does don’t matter if it can’t be paid for. There is at most $13 billion in state and federal funding for a project that has a price tag of $68 billion (a price tag that no one really believes is accurate). There is no prospect for further federal funding in an era in which discretionary domestic spending is being squeezed as never before. State funding of $250 million a year from fees from California’s nascent cap-and-trade pollution-rights market begins this budget cycle. But that is a pittance, and if they’re off the record, no state lawmaker will admit to wanting taxpayers to foot the entire bill. So why can’t the private sector come to the rescue? Because …

[Richard replies] Chris Reed’s funding analysis is simplistic and deeply flawed. First and foremost, virtually no project knows where all the funding is coming from at the outset. When we started BART to SFO, we were supposed to have $750 million in federal funding. We had virtually none for years and Sen. Dianne Feinstein and I walked out of Sen. Mark Hatfield’s office in 1994 with the first $25 million, which was a pittance. In the end, we received all $750 million and that was after Republicans took control of the Congress and 1994 and we were assured we wouldn’t get another dollar of federal monies. The California High-Speed Rail program has been held to a standard that no other program has had to face, which is to address calls for how the entire system will be funded, in advance. Nevertheless, here’s a broad outline:

- Cap and Trade dollars could provide billions for the project. The state talks of our allocation in terms of percentages because to speak of specific dollars would send signals to the carbon traders about what the expected the price of carbon credits. Still, the $250 million in first year funding is considered a modest amount compared to what future dollars would bring. Moreover, the cap and trade dollars, as more experience is gained, allow us to finance the construction of certain legs and build simultaneously, thereby reducing costs. Our $68 billion estimate includes inflation at 3% per year. Not only has inflation been below that amount, but for every year we cut off the construction time, we save about $1 billion dollars.

- Private Sector—Yes Virginia, there is strong private sector interest. People who talk about the lack of private sector involvement generally have no clue how the private sector works. Among other things, one should not want the private sector investment to occur at the outset, because the private sector prices risk and the risk would be highest then. However, our ridership estimates, which have been scrubbed by everyone from two independent peer review groups to the GAO, show that the system, as it is built out, will generate billions of dollars in excess of operating costs. Like the Japanese and other systems, our business model is to sell the rights to operate on our infrastructure to the private sector. We believe the NPV of the excess revenues will be between $12 billion for the initial operating segment and $20 billion for the line from LA to SF. At $20 billion, that would mean the private sector would be putting up about 1/3 of the system costs, doing that along the way to help us build out the full system.

- Development Potential—In Japan one-third of the revenues earned by Japan Rail East, one of the private sector operators of the Shinkensen comes from real estate development around the stations. We have not even begun to explore how to maximize that potential. In Arlington Virginia, station area planning resulted in such a dramatic explosion of mixed use development, generating such enormous property tax increments that the county was able to lower its other property taxes (source: Bob Dunphy, formerly with Urban Land Institute, now teaching at Georgetown). Senate President Darrell Steinberg proposed last year a bill that would allow for tax increment financing of any development within one mile of a high speed rail station. Sharing those tax increments with local communities would be appropriate, but we’d still be able to develop an enormous funding base.

- Use of the infrastructure—Again, we’re just beginning to look at maximization of the infrastructure we’d be building. Leasing the right-of-way (ROW) for fiber optic cable, as we did at BART, would generate significant revenues. Energy development in our ROW would be another money maker.

The point is that this is a long-term program. Our cap and trade funds are actually one of the more stable transportation funding mechanisms around (especially compared to the current situation of the Highway Trust Fund).

Finally, I do believe there will be additional federal support over time. Experience shows that to be the case, especially if legs of the system are up and running and it’s a matter of closing gaps, etc.

2. All the wonderful things the train allegedly does don’t matter if it can’t be built legally. No private sector investors have emerged despite years of promises from the administrations of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jerry Brown because Prop 1A included a provision that there could be no operating subsidies, whether the rail system was run by the state government or a private operator. No investor wants to partner with a suspect entity like the state of California without revenue or ridership guarantees that are tantamount to promises of subsidies if the project doesn’t meet expectations.

Prop 1A isn’t just susceptible to the NIMBYism that routinely hobbles big projects. The only lawyers who believe it is legal under the terms of Prop 1A work for the rail authority or for political entities that support the project. It’s already been blocked by a Sacramento Superior Court judge on the grounds that it has inadequate financing and insufficient environmental reviews to begin construction of its initial $31 billion, 300-mile link. That’s because of yet another Prop 1A safeguard: the requirement that construction couldn’t begin unless there is all necessary money in hand and completed environmental reviews for an entire rail segment that could be economically viable even if the statewide system were never completed.

I’ve had this argument with Chris before. Yes, there was an adverse judicial ruling. We think it was wrong and it’s on appeal right now. But regardless of the outcome of that, his analysis is again flawed.

The bond act says that we must build “useable segments.” The judge, looking at a preliminary plan produced by the Authority, concluded that the usable segment synonomous with what we called the “initial operating segment” a 300 mile long stretch from Merced to LA and said that we needed to show all the permits and funding for that.

However, the final plan that we presented to the Legislature defined the initial construction in the Central Valley as a useable segment and demonstrated that is was so because of the immediate beneficial impact of enhancement of existing rail service. The federal Surface Transportation Board, in approving that project, said it was doing so because the Central Valley portion had immediate utility.

As for the statement that no lawyers other than ours believe our project is legal, apart from noting that our law firm is the Attorney General of California, Chris overlooks the fact that the Legislative Counsel, the Legislature’s lawyers, were asked by Senators opposed to the project whether what we were proposing comported with the requirements of the Bond Act and the Leg Counsel said it did.

So, we do believe we’ll have access to the bond funding at some point, but we have sufficient federal and other funds available now begin key construction, which is getting underway right now

3. What the state of California wants to do isn’t even a high-speed rail project under the definition established in state law. Fallows somehow has missed the harsh critique of former state Sen. Quentin Kopp, the father of the bullet train idea in California, who opposes Brown’s plan to build a really fast train from San Jose to the northern edges of the Los Angeles exurbs. Kopp says—correctly—that Prop 1A promised a two-hour, 40-minute trip from downtown L.A. to downtown San Francisco. That’s not in the realm of even theoretical possibility if riders have to spend an hour getting from San Francisco to San Jose and then an hour getting from northern L.A. County to downtown L.A. on regular trains.

We are building a train that precisely meets the requirements of the bond act to be designed to achieve a 2 hour 40 minute travel time from LA to SF. That is true even though the 50 mile portion from San Jose to San Francisco will share tracks with Caltrain. You don’t have to take our word for it. The independent Legislative Peer Review Group looked at the planning and concluded that at present, our design would allow for that trip to occur in 2 hours and 32 minutes, well within the design parameters. Project critics have seized upon the “blended approach” to state anecdotally that they believe it means we could never meet the travel times. Actual engineering analysis demonstrates otherwise.

For 90% of the track we’re building, we’ll use brand new, dedicated rail. For the remaining 10%, in urban areas, we share track. This has no material impact on speeds (it may affect ultimate capacity, but we’ll have plenty enough capacity to meet our ridership projections).

Going back to plans published by the High Speed Rail Authority in 2008, long before Governor Brown’s team came on the scene, system maps showed that in urban areas the train would operate at slower speeds, more like 120 mph. This is consistent with experience around the world. The speed is determined by track geometry, i.e., the radius of the curve limits the safe speed. In urban areas, even if one is building entirely new track, trying to lay that in with long sweeping curves becomes prohibitive in terms of land use impacts. So, on those narrower corridors, the speeds are reduced. That is true whether one is using dedicated track or shared track.

We were asked by legislators, citizen groups and the independent Peer Review Group to consider using blended track in urban areas. We concluded we could do so and still meet the performance standards, but save billions of dollars for the next several decades.

Now it’s time for four more reasons that are a little more subjective but that Fallows still has no effective way to counter:

4. The Fallows case for the bullet train builds on information he was provided by the state and its paid consultants. Unless he is the most naive man in the world, he should be hugely suspicious of information provided by those pushing the project. Why? Because here is the short list of some of the many important things they have deceived the public and the media about since 2008:

The project’s cost (used to be $33 billion, then $98 billion, now allegedly $68 billion); annual ridership forecasts (117 million people, or three times as many riders as Amtrak, which operates in 46 states); jobs created; pollution reduction; and cost of fares.

This is a phony cost comparison. Project costs have increased to be sure, though not as much as people think when the comparison is done on a constant dollar basis. You can’t compare an estimate done in 2006 dollars with one done in 2013 dollars and claim they are directly comparable.

What’s much worse, however, is that critics took our efforts at transparency and turned them against us; we began to describe the project in both current year dollars and in fully inflated “year of expenditure” costs. So the $68 billion figure refers to the fully inflated cost of the project over its construction life. We’re the only people who describe projects that way. It’s like seeing the fine print showing that your $400,000 mortgage will cost you $900,000 over its 30 year life. Both numbers are “true” but you can’t mix them up unless you’re trying to make a polemical argument.

Chris Reed ignores the fact that it was Governor Brown and his team who came in and said the costs would be higher. We have been the ones to be honest about the costs. We also assessed whether the higher costs still justified the project and we concluded they did because (a) alternative means of providing that level of mobility would cost 2-3 times as much (an analysis reviewed by the GAO which found it reasonable) and (b) because once built the project would still operate without an on-going subsidy.

Governor Brown’s team also scrubbed the ridership projections to the point where independent experts believe they are reasonable. Our current ridership projections are about 29 million per year. Not sure where Chris got his number. Our number has again been reviewed by multiple peer review organizations and the GAO.

5. The public no longer backs the project. It won narrowly in 2008. Now polls shownearly two-thirds of voters are opposed. Costly projects surrounded by controversy and scandal—and lacking funding—need public support if they are to be completed.

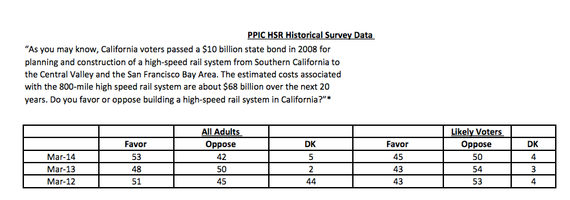

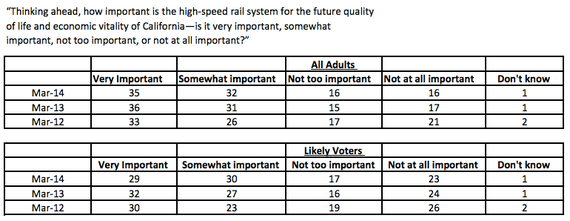

Well, there are polls and there are polls. Some of the most respected polling in California is done by the Public Policy Institute of California. Here’s an excerpt from a note I sent to s a reporter on this very subject, along with an extract of the PPIC polling. If anything, support has been consistent or growing slightly.

“The issue I wanted to call out was your phrase about the “increasingly unpopular high-speed rail system.” All journalists have a tendency to describe the project this way and it’s become part of the narrative. In fact, that statement isn’t consistent with polling data. Support for the project has been pretty steady over the years, despite controversy, lawsuits, some unfavorable court rulings and the lack of visible progress (i.e., “seeing dirt fly” as Nancy Pelosi likes to say). The most recent reliable polling shows that support has actually increased slightly overall, with a significant jump in the Central Valley. When I say “reliable” polling, I’m ignoring some Republican polls out of Orange County and really pointing to the PPIC poll, which also has the virtue of having asked the same question over the last three years.

I’ve included a table that shows the tracking of responses to the PPIC questions. [JF note: These are shown below.] For starters, the ballot measure won by something like 52-48 in 2008. Not surprisingly, the public is wary of big infrastructure projects in general. Since that time, support dipped a bit on occasion, but not by a huge amount. This year, the numbers are up a little; probably one could say that the numbers have been more or less even in terms of statistical significance.

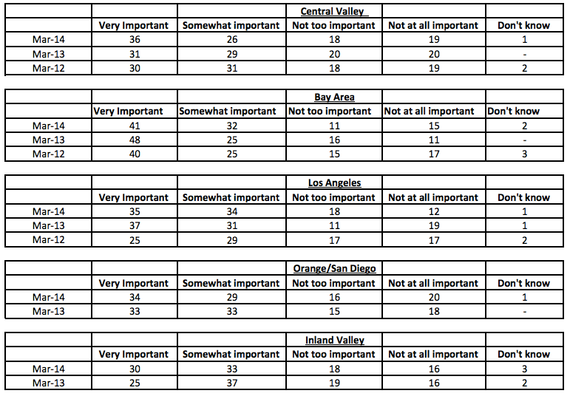

What’s most interesting to me are the responses to the question of whether high speed rail is very important or somewhat important to the state. Combining those two categories, as pollsters do in my experience, presently about 2/3 of all voters see the project in a positive light. In looking a cross-tabs and deeper questions, one sees in the polls that if the public believes the costs can be kept under control or come down, this number actually rises further.

You will also note that support is stronger among “all voters” than among likely voters. My unscientific analysis of that difference is that it displays a generational split. We all know that younger adults are less likely to vote than their seniors. Anecdotally, I’ve yet to meet anyone under 30 – Democrat, Republican, Progressive or Conservative – who isn’t excited about the train. I’m sure there are some out there, but literally (using the word in its literal meaning) I have not met them.

6. Many Democrats in the state Legislature have lost faith. The incoming Senate president, Kevin De Leon of Los Angeles, even said it was stupid to begin the projectin the Central Valley instead of the state’s most populated regions. And the most dominant special interests in Sacramento are public employee unions, not the building-trades unions which love the bullet train. These unions are extremely wary of another big mouth at the state trough. An enormously expensive bailout of the state teachers pension system has just gotten under way; a similar bailout of a program for retiree health care for state employees is still badly needed; and temporary income-tax and sales-tax hikes are expiring in coming years. These factors add up to a grim coming era in which there will be a perpetual dog-eat-dog fight for every dollar in the Legislature. These are the fights that the teacher unions in particular win year after year. There is no reason to think teacher unions will use their clout to help the bullet-train project as opposed to trying to enervate it.

Chris’ political thesis hasn’t played out. The State Building and Construction Trades and the State Labor Federation (which represents all labor organizations, including public employee unions) are all fully supportive of the project. Yes, some Democrats have come out against the project. For the most part, that opposition has been tied to spending money in the Central Valley, which is disappointing to see, but not unexpected parochialism. At the same time, we have the support of key Republicans, like the Mayors of Fresno and Palmdale, both of whom see the tremendous value of the project for their cities, along with the head of the Orange County Business Council and other GOP business leaders. They join with the Mayors of Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, Sacramento, Anaheim, the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, Fresno Economic Development Commission, Bay Area Council, Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, etc. etc. in supporting the project. Of course, we also have the strong support of the Governor, our two U.S. Senators, former House Speaker Pelosi and the majority of California congressmembers. No project will ever have unanimous support. We have terrific and deep support among leaders in California for which we’re very grateful.

7. The idea that trains dependent on conventional 20th-century engineering are the key to getting people around in 21st-century California is farcical to anyone who pays attention to the enormous building wave of transformative transportation technology. Driverless cars are only one example.

Driveless cars and other technologies are exciting, but have nothing to do with the high technology, high speed train we are building. Driverless cars may be how you get from downtown LA to where you’re going, but they really aren’t the way to get you from LA to San Francisco. Japan, China, Russia, Taiwan and a dozen other countries are investing in rail technology and there is plenty of innovation in the newest generation of trainsets, railcars, signaling and controls.

Fallows’ goal seems to be shoring up a project he perceives in trouble. But unless he moves out of his vacuum-based view of high-speed rail’s glories and addresses its California realities, he’s not even going to be a factor in debates over the bullet train—at least in the Golden State.

That’s because here, we’ve already heard all the happy talk. And we’ve noticed how little it meshes with reality.

I like Chris personally. We met once and we’ve exchanged notes a few times. However, he’s rabidly against the project and will remain so. We’re building a project that is consistent with the realities in California. It isn’t easy. The reality is that neither was the state water project, the state highway system, nor were building the world’s largest privately owned hydroelectric and geothermal systems. Californians weren’t daunted by those challenges. When did we lose confidence in our ability to overcome obstacles and make progress for the future?

For the record, here are some of the Public Policy Institute of California polls that Dan Richard refers to. The date column refers to asking the same question in March 2014, March 2013, and March 2012. If the print is too tiny to make out, the point is that the levels are more or less constant through that period. First, overall support:

Now, “how important to California’s future?” with variation between “all voters” (including young) and “likely voters” (older/whiter/richer).

Finally, “how important?” by region of the state.

That will hold us for a little while. When we resume: readers’ views; other supporters and critics; what history tell us; and why I am still on board.